Super User

Guide to planting a pond

By John Dyer

Northern Gamebird Manager

Auckland Waikato Fish & Game Council

Nearly 50 years ago I started planting around my pond on a lifestyle block. There has been plenty of time since to observe and reflect on which trees and shrubs lived up to my expectations and what I might do differently if I started again. These same observations should be of use to anyone in the same situation.

Firstly, many people overplant a pond. Waterfowl like to warm themselves on a cold day and shade themselves on a hot day, much the same as humans.

Sunlight drives many of the food chains they are relying on and a pond that is too shaded will inhibit this.

One group of ponds I can think of epitomised this and the owner said they were better off before he planted them. Eventually the chainsaw came out and his pond cover was radically thinned, with a great deal of effort.

Sunlight is also important to maintain ground cover for ducks to nest in and a generally open pond is much more inviting and easier for ducks to fly in and out of. A gap cut in the trees can also direct them when they exit the pond.

If you are thinking about this, note where the sun comes from to shine on a pond and not just today but as it swings around the horizon at different times of the day or year.

If planting large trees, their shade would be better falling away from the pond and save the up-close stuff for shrubs.

For instance, flax flowers attract tūī and the small shiny seeds are eaten by pheasants. It is most useful when its leaves fall over the edge of the pond.

This provides good cover from hawks which will wait for ducklings to emerge to pick them all off. With lots of edge cover, the hawk is left watching the spot where the brood went in, while they more safely relocate further along.

When providing shade, it should be relatively open. If you look at ducks sunning themselves on a log that you have supported in place for them, (because otherwise, like the iceberg, much of it will sink out of sight), you’ll notice they are all spaced in such a way that if they get a fright, they can easily take off without all their wings clashing. So trim back trunks at ground level to allow this quick getaway and leave higher branches to provide leafy shade.

down toward the pen floor, it was every duck for itself as they raced to get their ‘manna from Heaven’. Pin oaks are another good variety to plant and I sometimes hear that “mine don’t fruit”. I thought this true of mine too until I put a game camera there to watch a trap. In the background I wondered why pheasants kept turning up.

A scratch in the pin oak leaf litter told me what I’d overlooked, the acorns were there all along but covered up. The birds certainly knew they were there.

Pin oaks are water tolerant (flooding, for instance), but not if it is year-round saturated.

Relocate that tree and watch it pull away.

Another scenario is when oaks line a farm drive. Passing vehicles crush and kibble the acorns and that makes them even more attractive for many waterfowl including pūkeko. Conversely, if your oak is planted in thick grass, the acorns are probably only really available to rats. Any tree needs to be fenced off from stock, of course, but you could perhaps put oaks on the edge of the fence and eventually overhanging it, so their acorns fall in the open.

Some oak species produce acorns that may be too large, though I have seen mallards carefully work turkey-oak acorns (the largest of acorns), until the point is facing outwards before they swallow it. Turkey oaks are one of those self-sterile species that will not fruit unless there are two of them.

Water oak (Quercus nigra) is a rare tree in New Zealand but there's one that I have collected seed from each year as it is a proven performer overseas. Same with water hickory (Carya aquatica).

Holm oaks are very salt tolerant, if you are near the coast. They have lots of useful sized acorns in April/May, especially if sourced from one parent tree by the main road at Pūkekohe Golf Club.

They are very water tolerant and I know of a number growing right on the Waikato River’s edge, being covered by each tide. Grey ducks, and I am sure mallards also, love the epiphytes (the flax-like plants) that grow on puriri branches.

If there is a branch growing over water with any gap in the epiphyte root mass that will support a nest, then it will be used year after year, provided you keep possums under control as they compete for these spaces.

How do the ducklings get down? They jump and regardless of the height of the fall, they bounce, pick themselves up and off they go. When the peeping from the nest stops, the mother duck assumes she has the lot and into the pond cover she takes them.

I have seen a grey teal gathering her brood this way under a nest box. They make a special quiet quack to call to those still in the nest.

Hearing this, a hawk straight away flew into the nearby tree and two pūkeko came running like the dinner gong had just been sounded.

This brings me to the next planting project, planting overhead cover in the water. Willows will establish, of course, but grey willow can be extremely invasive, and I can think of ponds, which used to be wonderful, but are now completely hidden by willows.

A similar species that is much better behaved is weeping willow. The cascading branches hanging in the water make good hawk cover, but be careful not to crowd a pond. One or two of this species on the edge might be ample.

All you need is a small pole to start it off. Make sure the pole is the right way up! If twisty willows are on sale at the nearby nursery, look away. I have never seen this species provide any benefit.

Swamp cypress is a tree that will actually grow in standing water and the “knees” it produces will make good places for ducks to climb out and roost on. It might tend to spread in the South Waikato downwards, but north of this it seems well mannered.

Climate will influence your choice of plants. For instance, I notice rowan trees in Rotorua thrive and are laden with fruit that birds love, but in Auckland and north, they’re misshapen and of little value.

Conversely, monkey apple trees (Acmena spp.) will thrive and produce abundant berries in Auckland and north that wood pigeons love, but frost will kill them off south of the Bombay Hills. Both rowan and monkey apples are now regarded as pest species, so there’s another thing to be mindful of.

Coprosma (karamu) is a native shrub that has orange berries, sometimes in profusion. If you have a green thumb, why not take cuttings from the most fruit laden examples you see. Everything from quail upwards likes Coprosma seeds, especially C. robusta.

Be careful that nurseries like to crossbreed new varieties and prostrate shrubs, which might be great in the garden, but will soon be overcome by weeds in your fenced-off pond area.

A native plant nursery is much more likely to have the uncorrupted parent plant.

To establish trees, talk to your friendly carpet outlet. What you’re wanting to do is to raid their skip for the old woollen (not nylon) carpets they’ve pulled up and thrown away.

You can quickly cut these into say 0.5-metre squares with a sharp skill-knife. Then cut a slot from one edge to slip around the tree truck.

If you have pūkeko, I strongly suggest you get a green plastic Poly Logic sleeve which you can put around the tree using three or four scrounged bamboo stakes. Pooks will walk past these and not realise the young tree is inside.

Otherwise, they are very likely to pull it out. Water and weed your trees well in their establishment years.

Thereafter they will look after themselves with perhaps a bit of pruning to get the good central bole you want. Don’t let the cattle in even for a short while. They will go for the trees before the grass and set you well back.

At any rate, if the grass is allowed to grow rank in spring, the ducks will have a much safer place to nest compared with a mowed or grazed pond paddock.

Likewise, be sure to set a Timms trap for possums as these can ruin a tree in just one night by breaking that tender young apex shoot.

A well planted pond is a joy to reflect on. Good luck.

A long road that doesn’t have a turn in it

Farmer and conservationist Russell Langdon is philosophical about the recent flooding that swept through his property.

Russell Langdon, 89, has had his share of challenges at the wetland reserve he has established on his farm in Mid-Canterbury, near the South Branch of the Ashburton River.

The May floods were the latest hurdle. “The river broke out and came right through here. It flattened a few fences and damaged aviaries, but it’s nothing we can’t handle. The birds survived all right.”

He said the clean-up at Riverbridge, however, would take a long time. Riverbridge Conservation Park is an 8.3ha wetland habitat with half-a-dozen ponds and enclosures for native wildlife on Russell’s farm at Lagmhor, near Westerfield, southwest of Ashburton.

Among the birds he breeds are brown teal/pāteke and kākāriki. He used to breed whio but a freak snowstorm in 2010 put paid to that.

The whio enclosure was destroyed and the ducks were gone. The Department of Conservation removed Riverbridge from the whio breeding programme, and now it says Orana Wildlife Park and the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust fulfils the requirements.

Russell has had plenty of run-ins with bureaucrats over the years – “they weren’t raised under a hen like me” but he takes it all in his stride. As he says, “It’s a long road that doesn’t have a turn in it”.

His land sits on top of an old river bed and the natural water level lies only a metre or so down, making it ideal wetland country. The land slopes east towards the sea “about 30 feet to the mile” so if you dig down and plug up both the eastern and western sides of the hole, a pond will form naturally. Russell grew up on a farm at Westerfield that his father bought after World War one, and so he only moved a short distance when he bought his farm at Lagmhor 40 years ago “when sheep were king”.

Russell’s stock numbers soon grew from 800 to 4000 and, along with a stint in the farm machinery business which involved a lot of travelling, selling mainly Case headers, he led a busy life. Riverbridge was just farm paddocks when Russell started transforming it into a habitat for waterfowl and other birds. It is now a fully formed wetland with ponds and native forest, mostly unplanned and planted to encourage wildlife to thrive.

Russell says his family were all great tree planters and he has planted 1000s of trees over the years.

Riverbridge started taking shape 21 years ago when Russell planted trees as a millennium project. “We made a lot of mistakes but who hasn’t.”

Among the trees on the property are matai, kahikatea, totara, cabbage trees, olearia, coprosmas, flax, kowhai and lacebark.

He says he still has a lot more trees to plant, with a hand from his brother John, two years his junior.

Just inside the entrance to Riverbridge is the old Westerfield schoolmaster’s house, built in 1888. Russell bought it in 1964 and relocated it to host school groups and tourists.

At the time, DUNZ had a South Island chapter, and Russell had had plans to use it as accommodation for DU members and other groups.

The walls are lined with information about wetlands, posters on endangered species and newspaper clippings about the park.

The wetlands start and stop in the property, so there’s no predatory trout, making it a safe environment for the critically endangered Canterbury mudfish.

Russell also has plans to introduce freshwater crayfish/koura into the wetland. The biggest pond is quite shallow, making it ideal for wading birds including pied stilts, spoonbills, and scaups and shovelers are also happy there. There’s marsh crakes too but they are hard to spot, and some buff weka.

Sharing the kākāriki enclosure at Riverbridge are a pair of Reeves’s pheasants though the male needs to be moved and Russell is not looking forward to that task. “If you go in there, he takes to you,” he says.

The lower part of the pāteke enclosure is covered in aluminium mesh which allows bugs in, but no predators.

The park is protected by a QEII convenant and it receives funding through grants applied for through the Riverbridge Native Species Trust. These days, Russell, who was awarded a QSM in 2006 for his services to conservation, says he potters around Riverbridge, leaving the farming to his nephew – and for now his focus is on cleaning up after the floods.

Wairio on show

About 30 people braved squally rain on Sunday, May 9, for a guided tour of Wairio Wetland led by Ducks Unlimited NZ President Ross Cottle and Director Jim Law.

The event was a Rural Women New Zealand annual event to raise money for the Associated Country Women of the World to help fund community projects in developing countries.

Before setting out, Ross and Jim told the visitors about DU’s long involvement with the wetland – from Stage 1, its initial project about 17 years ago through to the latest development in Stage 4.

Ross said the wetland’s only water source in 2005 was courtesy of high wind dumping water into it from Lake Wairarapa to the west, but it didn’t retain it, and the water flowed straight back into the lake.

DU put in a bund wall, which was moderately successful, holding the water through the bird breeding season, but by December, it had dried out.

The next step was to dig down to a lower level to keep the water there longer, which was more successful, holding the water till the birds had bred and fledged. At the same time, DU planted out native species and these are now well established in Stage 1.

From there, it was on to Stage 2 and 3, and every low spot was fenced off with a bund wall.

Stage 3 was handed over to Victoria University because “we wanted some science behind it”, Ross said. It was envisaged that the project would provide a template for wetland restoration.

“Next thing, someone had a bright idea to put in a bund wall” between the three stages and the lake. About two weeks later, a mighty wind blew water in from the lake and “we had 100 acres of water”. After that success, DU extended the bund all the way back to Stage 1.

This was “amazingly successful” and has created a wetland of more than 250 acres of water.

“We were successful beyond our wildest dreams,” Ross said.

Jim said Wairio had been a ground- breaking project, with the Department of Conservation handing over the wetland’s management to DU – at the time it was unheard of for DOC to hand over restoration of its land to a local group.

“It only took us two years to convince DOC to let us spend our money on their land.”

DU has spent more than $200,000 in the past 17 years. About half of this has come from donations, which began rolling in once people saw how Wairio was being transformed and the return of wildlife.

On the 4.2km walk, Jim led the visitors along the bund wall track through Stage 4 of the wetland, where he described DU’s vision of the future – when stands of kahikatea would replace the current open areas of fescue.

With a rainbow in the background, and Ross bringing up the rear in his side-by-side to assist any stragglers, the tour covered Stages 3 and 2 before reaching its conclusion at Stage 1.

On a small detour from the main track to the water’s edge at Stage 4, the group had a preview of the proposed site for a viewing hide which DU has built. It is now waiting for a resource consent to place it on the site.

Birdlife has flourished at Wairio since DU took over, and the number of royal spoonbills, which previously had not been seen for 30 years, have surpassed 100, and they are breeding there.

Bittern numbers have remained stable in the past four or five years, despite a continuing decline throughout the rest of New Zealand.

Over a hot cuppa back at the cars, the visitors said the tour had been a revelation and they were highly impressed with their tour guides’ continuing passion and enthusiasm for the project.

Boardroom above the clouds

DU Director Dan Steele hosted a DUNZ Board of Directors meeting at his place – Blue Duck Station on the banks of the Whanganui and Retaruke rivers – over Queen's Birthday Weekend in June.

The visit included the formal board meeting and a tour of the station, including a trip up by ATV to see The Chef's Table, the restaurant that Dan co-owns with acclaimed English chef Jack Cashmore.

The restaurant's hilltop location has spectacular 360-degree views of Tongariro and Whanganui national parks, and though Mt Taranaki was shrouded in cloud on the Saturday morning, Mt Tongariro, Ruapehu and Ngauruhoe more than made up for the no-show.

Other ports of call on the tour of the station included the old homestead perched on the bank of the Whanganu River where Dan's parents live, and, up the Retaruke, the remnants of the ill-fated Berryman bridge, which collapsed in 1994, killing beekeeper Ken Richards.

Dan's colourful warts-and-all commentary on the history and characters of the region was eye-opening and capped off an entertaining and educational weekend.

Zealandia calling

It's time to send in your registration for DUNZ's 47th Annual Conference and Dinner, which will be held in Wellington on August 20-22.

The conference venue, the James Cook Hotel Grand Chancellor on The Terrace, has direct access by lift down to the shops on Lambton Quay.

Saturday's field trip to Zealandia promises a glimpse of some of the 40 species of wildlife thriving within the predator-free fence of the 225-hectare urban sanctuary.

A silent auction will be held as usual in conjunction with the Saturday evening dinner.

The James Cook has agreed to hold rooms for DUNZ members until July 20, so if you wish to stay in the hotel, make sure you register for the conference before then.

Contact Mary and Paul Mason at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. for more information, or post your registration form to PO Box 165, Featherston 5740.

From the President

The duck shooting season is upon us so I would like to share some observations I have made.

Some long-term hunters (50-plus years) say the season has been one of the worst they can remember.

Fish & Game has been telling us that the bird counts are 15 per cent better than last year. Frankly, I do not believe it.

The paradise duck numbers appear to be doing OK, along with the grey teal, but the mallards seem to be in real trouble.

Fifteen years ago, the pond in front of our house was crowded with ducks when the duck shooting season was on; that is not the case now with fewer than 20 birds there at any one time.

I was talking to Anne Richardson at Peacock Springs last month and she said there used to be hundreds of ducks camped there during the season; now there are hardly any.

I have three reasons why I think this is:

• The introduction of steel shot

Steel does not have the same killing power of lead. This leads to a lot more wounded birds that fly away and die elsewhere and do not get counted in the daily bag.

• The unpinning of semi-automatic shotguns

This allows five shots to be fired and creates many more wounded birds because they are much further away.

• The season is too long

When I first started shooting, the season was the month of May – four weeks and then it was over. I would like to see it

reduced back to that again.

The birds are pairing up now and to give them the best chance, they need to be left alone.

Curiously, the major decline of the mallard population started about the same time as steel shot and unpinned shotguns were allowed.

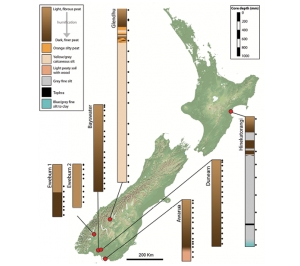

Tracking wetland changes through eDNA

A study has shown that environmental DNA, known as eDNA, may be valuable in measuring biological changes in wetlands. The eDNA is extracted from soils, air, water, and other substrates.

Researchers from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research sequenced microbial DNA from soil cores taken down to 4 metres below the surface in seven New Zealand wetlands in one of the few studies globally to have studied wetland microbes at such depths.

“The results showed distinct changes in microbial communities as we went deeper,” says study co-author Dr Olivia Burge.

Biodiversity monitoring in wetlands tends to focus on large organisms such as birds and plants, which can be relatively slow to respond to environmental change.

Lead author Jamie Wood says the strength of eDNA is that it allows researchers to study microbial groups (bacteria and archaea), which may respond faster to environmental change.

As a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission. This is

a process driven by microbes, and the researchers saw an increase in the types of microbes responsible in the upper

layers of the more modified wetlands.

“An unexpected finding was that the effects of drainage also appeared at greater depths, below the water table, where the relative proportion of microbes responsible for carbon fixation and methane generation decreased,” he says. As part of the study, the researchers compared three similar wetlands with different degrees of human modification. When a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission.

“Ultimately eDNA may provide a useful tool for monitoring real-time wetland condition and identifying when critical thresholds are being approached,” says study co-author Beverley Clarkson.

Pukaha farewells leading lady

Pukaha Wildlife Centre's summer was overshadowed by the death of their treasured white kiwi, Manukura, who was farewelled in a special service on January 9.

However, Pukaha’s captive breeding ranger Tara Swan says there have been "lots of positive, happy things happening in the bush since our dear Manukura left us”, including the hatching of her 'niece or nephew', a chick from Manukura's brother, Mapuna.

"The little white patch you can see on the tip of the chick's head is almost like a little throwback to the white feather gene of Manukura (someone called it 'Manukura's kiss')," she said.

"We have had so many yellow crowned akariki hatch, with 16 fledglings and five still in the nest across two pairs, and all our kaka have been successful this year, with five kaka fledged across the aviaries," Tara said.

These birds will be released at Cape Sanctuary in Hawke’s Bay later on in the year.

What bird bands tells us

Anyone reporting a duck band is eligible for some great prizes, so leaving bands in the maimai is a sort of lose-lose for everyone.

The first group to use modern bird bands in New Zealand was the Southland Acclimatisation Society in 1911. It ordered 100 aluminium bands from the United States marked “S” and 1 to 100.

These were fitted to mallard ducks reared at its Mataura Hatchery that were then taken 60 kilometres away by rail to be released on Mr Foster’s lagoons at Thornbury.

Though they had never seen the outside of their rearing pens, within a few weeks, a pair had found their way back to the hatchery.

Banding not only reveals the uncanny ability of ducks to find their way around the globe, but also provides vital information to waterfowl managers about the health and survivorship of waterfowl populations.

Southland’s experiment was soon dwarfed by the NZ Wildlife Service and other acclimatisation societies working together from about 1947 onwards to band thousands of mallard and grey ducks.

The early banders used peas as bait and made traps out of willow hoops covered in wire mesh next to lakes like Waihola near Dunedin and also in the Wairarapa.

Back then, bands were made from aluminium, but more recently are made from stainless steel supplied by a Swedish firm. These come pre-numbered with a DOC return address – the department collectively administers all the non-game bird banding scheme records as well.

At present, anyone reporting a duck band is eligible for some great prizes, so leaving bands in the maimai is a sort of lose-lose for everyone involved, not least the ducks themselves. If you find a game bird band, the 24/7 freephone to report it is 0800 BIRD BAND.

Why not do it on your mobile as soon as you get your band before it gets mixed up with other bands or lost. One unique mallard band from Australia, shot in Gordonton, Waikato, was lost for 20 years until it was found under a carpet.

Auckland-Waikato and Eastern Fish & Game are now the main duck banders, with thousands of birds being banded each year. Some individual catches in the Hauraki Plains have well exceeded 1000 in one hit.

Maize is placed where ducks frequent, and they tell all their mates. Slowly, the ducks are accustomed to having cages nearby until they take them for granted. Volunteers play a key role in feeding out and also on the day of the catch, helping process birds and some even help Fish & Game staff to band the ducks under close supervision. It’s a great family affair as kids are a useful height in the low cages.

Birds are recorded as adult or juvenile, male or female and mallard or grey. Grey hybrids are also noted but beware that mallard males undergo what is known as an eclipse plumage in which they lose their distinctive green head and chestnut breast.

They instead assume a temporary summer plumage much more like the female mallard.

As this is a progressive moult, they are found in various stages and I suspect a lot of speculation about hybridisation is simply about eclipse drakes that would look exactly the same even if they were the only species present. The same bird in winter might be a classic greenhead. In the hand, a true grey has just one solid white bar on their lower wing speculum whereas the mallard has two distinct larger bars above and below. Birds that have 1½ tend to be hybrids. However, DNA tests have revealed that almost all greys now have mallard blood in them and vice versa.

It is worth noting, however, that when modern duck banding traps are located next to the few remaining large wetlands – the natural historic habitat of the native grey duck – we still get good numbers of them.

However, the problem is that most of these freshwater wetlands have long since been drained for agricultural production – 99 per cent in Rodney area, for instance.

The grey duck collapse in the Waikato actually preceded the mallard establishing even rudimentary bridgeheads by at least 10-years and was instead closely tied in with huge-scale wetland drainage projects of thousands of acres.

Without the adaptable mallard today, which is far more at home in much-modified environments, it is doubtful we would still have duck seasons as we know them.

Banding has shown some impressive results. Most mallards are sedentary types that rarely venture 20 kilometres from their banding site, but some turn up in all sorts of places around New Zealand.

A few mallards banded in New Zealand have found their way overseas to such places as New Caledonia and French Tahiti.

If you think about how difficult it would be to navigate a plane to find a small island 2000km away, even the smallest error would mean the ducks’ certain demise in the vast Pacific Ocean.

This is an even more incredible accomplishment than the annual migration of mallards in North America and Europe, their natural homes, as there is no historic template for these Pacific travels.

In droughts, it was thought ducks vacate their region for wetter ones, but banding has shown they instead simply move from dry wetlands and ponds to nearby larger rivers and coastal areas, returning when heavy rains again hydrate inland waterways.

The primary purpose of banding is for us to obtain population estimates, survival rates and harvest rates from which to judge the appropriate length of the game season, limit size and so on.

In particular, we notice that juvenile female mallards, which are vulnerable not only in nesting time but also while brood rearing, suffer high hunting mortality rates.

The drakes on the other hand are free to 'swan off' once incubation begins and their increased survivorship reflects this. This is why we recommend 'Go for Green' to hunters, meaning aim to harvest those surplus drakes.

Banding game birds has also been used to study black swans, Canada geese, paradise shelduck, released pheasants and partridge as well as wild quail. Though shoveler ducks are extremely hard to catch, dedicated researchers managed to band enough broods to gain some appreciation for their life history and large-scale movements the length of New Zealand. Likewise, with grey teal, which can be caught in nest boxes.

Because of banding we know that grey teal often come back to nest in the same nest box every year, sometimes rearing two broods in a single year. This makes them very productive.

If any DU members would like to participate in duck banding, Fish & Game is always looking for helpers particularly in the Auckland-Waikato and Eastern regions.

Why not come along and find out where all that duck bling is coming from.

Contact the author and register your interest to be notified closer to banding time.

Our magnificent seven (RAMSAR Sites of NZ)

To celebrate World Wetlands Day on February 2,

which marks the signing of the Ramsar Convention in 1971, Department of Conservation staff provide a rundown of Ramsar sites in New Zealand.

More than 10,450 hectares of Wairarapa Moana became a Ramsar site in August – including the Wairio wetland that Ducks Unlimited has been instrumental in restoring.

The designation highlights the importance of the large and varied wetland which is home to more than 50 threatened species such as tarapirohe (black-fronted tern), tuna (longfin eel) and panoko (torrentfish).

Though Wairarapa Moana has been getting most of the attention recently, there are six other Ramsar sites spread across Aotearoa – some of which have been recognised since 1976.

Some are accessible to the public and, with overseas travel curtailed because of Covid-19, it may be a good time to explore these special places.

Firth of Thames, Waikato

The Firth of Thames is one of two internationally significant Ramsar Convention wetlands in DOC's Hauraki District. The tidal estuarine environment is a biodiversity hotspot for a range of bird species: in peak season more than 20,000 birds can be found on the tidal flats and mangroves between Thames and Pukorokoro-Miranda.

Among the species found across the 8200 hectare estuary are godwits, knots, skua, oystercatchers and tern, plus dozens of others.

The Firth is a key location in the East Asia-Australasian flyway, the lengthy and internationally significant pathway for many migratory bird species in the wider Asian-America-Pacific region.

In fact, it’s the birds that are particularly vital to giving the Firth its Ramsar status, such is the site’s importance to the ongoing protection of the assortment of species.

DOC has a long relationship with the Miranda Shorebird Centre, on the western coast of the Firth of Thames, where visitors can learn about the various species before venturing to the shore to observe the birds for themselves.

DOC’s usual advice applies for visitors – enjoy the birds from a distance, do not get too close, take only photographs (or video) and leave only footprints. The Firth is suitable for more experienced and competent kayakers and canoeists, but those venturing into the area should go properly prepared – wear lifejackets, take communication methods, and advise someone of your plans for the day.

Conditions in the Firth can change quickly and visitors should check tides.

Whangamarino, Waikato

About a 45-minute drive north of Hamilton lies the internationally recognised wetlands of Whangamarino. The 7000-hectare mosaic of swamps, fens and peat bogs has been a Ramsar site since 1989. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for the public to get up close and personal to the raised peat bog as they are both treacherous and delicate – people traipsing through can damage sensitive plants, disrupt cryptic bird species and may introduce noxious weeds into a habitat where they are extremely hard to control.

Those wanting to catch a glimpse of the wetland can visit the Whangamarino Redoubt and Te Teoteo pa or the Meremere redoubt. While in some areas, there is a boundary of introduced willow, just inside this fringe are expansive native wetlands where you can see the endemic wire rush (Empodisma robustum) and tamingi (Epacris pauciflora), key species in the raised peat bog of Whangamarino.

Hiding beneath these are some very rare orchids such as the critically endangered swamp helmet orchid.

There are three rivers, the Whangamarino, Reao and Maramarua, on which kayaking and boating is permitted. If you move slowly and quietly, you may just glance the critically endangered matuku (Australasian bittern).

Whangamarino is home to a wide range of threatened flora and fauna including the swamp helmet orchid, tētē (grey teal), pūweto (spotless crake), black mudfish, North Island fernbird and weweia (dabchick).

Whangamarino is one of two Ramsar sites being enhanced through DOC’s wetland restoration programme, Arawai Kākāriki.

Awarua-Waituna Wetland, Southland

Just a short drive from Invercargill is the 20,000-hectare coastal lagoon, wetlands and estuary system of Awarua-Waituna, one of the largest remaining wetland systems in Aotearoa. The dynamic lagoon periodically opens to the sea, changing its waters from freshwater to estuarine.

The area is home to a wide variety of rare and threatened birds, fish, lizards, invertebrates and plants, including matuku (Australasian bittern), tūturiwhatu (NZ dotterel), koitareke (marsh crake), giant kōkopu, tuna (longfin eels), and several threatened species of moth.

Several walking options ranging from 10 minutes to two hours are on offer. These start at the lagoon and head through the wetlands on a mixture of boardwalks and gravelled tracks and offer good opportunities for spotting wildlife. Kayaks and small boats can also be used on Waituna Lagoon during high tide or when the outlet is closed. Awarua-Waituna is one of two Ramsar sites being enhanced through DOC’s wetland restoration programme, Arawai Kākāriki.

Farewell Spit, Golden Bay

Found at the north-west corner of the South Island, Farewell Spit is the longest sand spit in Aotearoa at 25 kilometres long.

An area covering over 11,000 hectares was listed as a Ramsar site in 1976.

Both estuarine and freshwater wetlands occur and it supports an array of rare habitats in the dune system.

The area is an internationally renowned bird sanctuary with more than 100 species recorded in the area. In spring, it attracts thousands of migratory wading birds from the Northern Hemisphere. During summer, the immense tidal

flats can support more than 30,000 shorebirds, a magnificent sight.

Visitors can walk a short distance out from the base of the spit (but should

stay on the beaches and marked tracks to avoid possible quicksand), but those wanting to travel the full length to the lighthouse at the tip will need to join

a trip from one of the licensed tour operators.

Manawatu River Estuary, Manawatu

About five minutes’ drive from Foxton is the Manawatu River Estuary, which was designated a Ramsar site in 2005. The 200-hectare estuary is an important feeding ground for international migratory birds and offers diverse birdwatching opportunities, including several threatened species such as, ngutu pare (wrybill), matuku (Australasian bittern) and taranui (Caspian tern).

Much of the wetland is saltmarsh which is difficult to access but there is walking access from off Holben Parade near the picnic shelter to the sand and mud flats There are two bird viewing platforms in the area.

Kopuatai peat dome, Waikato

About 25km inland from the Firth of Thames, on the Hauraki Plains, lies the Kopuatai Peat Dome. The 10,000-hectare site is the largest raised peat bog in New Zealand, and is unique globally. Kopuatai is a highly sensitive ecological environment, and as a result, DOC asks wetland enthusiasts to respect requests not to visit the sensitive wetland areas. Access to Kopuatai is not straightforward: the site is surrounded on all sides by privately owned land, and so visits are by arrangement only and require planning.

DOC’s Hauraki District staff can work with researchers and scientists

to arrange visits to Kopuatai, but this takes time so early contact and detailed planning are required.

■ For more information on NZ’s Ramsar wetlands, please visit doc.govt.nz.