Super User

New members for this quarter

(F) denotes Full membership

(S) denotes Supporter member

(T) Trade membership

Grey Teal to Nga Manu Trust

The birds are to be released at the Nga Manu sanctuary near Waikanae which has a park-like setting with bush walks,

swamps and ponds.

DU Exports NZ Shoveler

August, sent by Ducks Unlimited.

Our cover shows DU member Julian Hayes about to place the first of the shoveler into the export crate.

Spoonbills New Zealand

Reports of sightings in the past decade point to a growing population of royal spoonbills in New Zealand. Te Papa bird expert Dr Colin Miskelly backs this up, saying there are signs that the spoonbill, kotuku ngutupapa, is "increasing at a rapid rate".

The first spoonbill sighting was recorded in New Zealand at Castlepoint in 1861.

Sightings increased through the 1900s, with breeding first recorded next to the white heron colony at Okarito, south Westland, in 1949.

Since then it has successfully colonised New Zealand from Australia and is now widespread, breeding on both main islands, and dispersing to coastal sites across the country after the breeding season.

In 1977 the New Zealand population was estimated at 52 birds. The most up-to-date estimate (in 2012) was 2,360 birds, though the population is now thought to have exceeded 3,000.

A colony and nest count during the 2013-14 breeding season found 19 colonies with at least 614 nests.

It breeds in the exposed canopy of tall kahikatea trees, on the ground near estuaries, rivers and harbours, in reeds, in low shrubs, and on steep rocky headlands, tending to breed near white heron and shag colonies.

It prefers freshwater to saltwater but can inhabit both. Royal spoonbill is one of six spoonbill species worldwide but the only one that breeds in New Zealand.

Source: Szabo, M.J. 2013 [updated 2017]. Royal spoonbill. In Miskelly, C.M. (ed.) New Zealand Birds Online. www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz.

AGM 2020 Minutes

Ducks Unlimited New Zealand 45th Annual General Meeting,

3 August 2019 9am, Quality Inn, Whanganui

President Ross Cottle welcomed members to the 45th Annual General Meeting. Welcome to guest speaker Murray Stevenson.

APOLOGIES:

Liz Brook; Dawn Pirani; Paul Pirani;

John Cheyne; Sharon Stevens-Cottle; Myra Smith; Glenys Hansen.

Motion: That the apologies tendered are accepted. Moved: John Bishop. Seconded: Jan Abel. Carried

MINUTES OF THE LAST AGM Circulated and copies available at the AGM.

Motion: That the minutes of the last AGM be accepted as a true and complete record. Moved: Will Abel. Seconded: Di Pritt. Carried

PRESIDENT’S REPORT – READ BY ROSS COTTLE

Moved: Ross Cottle. Seconded: Adrienne Bushell. Carried

Financial Report – John Bishop

Explanation of charitable trust requirements. Revenue stream Pharazyn, Treadwells, Muter Trusts, John Mortimer, South Wairarapa Rotary. South Island trip by Ross and Jim around $600 annually. Board of Directors expenses minimal, lot of meetings by Skype with annual trip to Ohakune.

Motion: That the financial report be accepted. Moved: John Bishop. Seconded: Di Pritt. Carried

Waterfowl and Wetland Trust Report – David Smith

The Trust is in good shape. The 2017 balance in Trust $516,000-ish, since then paid $40,000 to DUNZ. Currently $510,394, money paid out covered by Trust. Original fund $200,000 twenty years ago.

Motion: That the Trust report be accepted. Moved: David Smith. Seconded: John Bishop. Carried

Election of officers

Board selects President Ross Cottle, Vice-President Dan Steele, Director William Abel. Nominate Jim Law, John Dermer to stay on. Nominated: Di Pritt. Seconded: Jim Campbell. Carried

Wetland Care – William Abel

2019 short on projects, centred on Wairio and project in Masterton.

Royal swans – William Abel

No trip to South Island, no swans and no cygnets.

Website – Paul Mason

Membership – 280 members, 57 still to pay subs. Includes 61 life members, honorary members. Moving more to electronic payments. Survey done on email/post preference for communications. Flight magazine available on website, can be searched by subject. More of the earlier magazines are being scanned on to the website.

Wairio Wetland – Jim Law

Reticulation of water from Matthews and Boggy Pond. GWRC has done work reticulating. Less has been spent this year – about $5,000. Reticulation funded by GWRC – around $30,000. DUNZ has spent $220,000 in total on Wairio. Partners are GWRC doing predator control, DOC – cutting grass on track. Victoria University – research sites at Wairio, planting more specimen trees. Planting day in July with a good write-up in Times Age. Ross took reporter Piers Fuller around wetland who wrote a national article on Stuff. Restoration committee has $10,000 in Trust. Significant donation of $15,000 also in Trust. Members should feel proud of this project.

Whio, blue duck – Peter Russell

Released 72 birds, North Island around 30 at Blue Duck Station. First release in 2000 was 7 birds. Flocks in South Island in three areas. Tasman , concern because of mast year with success because of

trapping and 1080. Successful year.

Scholarship

Three-year trial of 4 students – $5,000 each, Victoria, Massey, Christchurch, Waikato. Possibility of 1 Victoria student in 2020 to work at Wairio. Emma has given suggestions to unis of topics of study.

General Ian Jensen – vote of thanks to Board members and for the organisation of the AGM weekend.

Meeting closed at 10am.

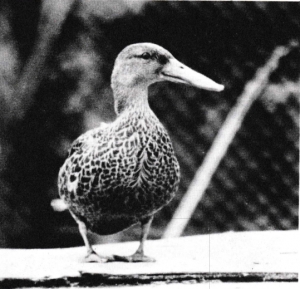

Look out for grey teal bands

DU member John Dyer wants to enlist members’ help in tracking grey teal and reporting on any banded birds they come across.

Small numbers of grey teal (tete), which have been known to fly the length of the country, are being banded near Pokeno, Waikato, so you might find a banded grey teal anywhere between Kaitaia and Invercargill.

The band in the photo is the style being used; marked “SEND DOMINION MUSEUM NEW ZEALAND”. At one stage the Dominion Museum in Wellington administered bird banding before the Wildlife Service and later Department of Conservation took on that role.

Some of these older bands are still being used and some longer-lived birds that were around then are probably still alive. Grey teal, however, tend to have a much faster natural turnover and a five-year-old bird is an old one.

It’s suggested any recovered bird band details, (number, species, where, when, how, who found it and your contact details), should be registered by phoning 0800 BIRD BAND, which is a freephone, 24/7 number. You can also go online.

Keep the band somewhere safe and if you don’t get a reply, chase it up. This 0800-number also applies to mallard/ grey duck bands.

If you are cleaning out grey teal nest boxes, be aware that if you find a skeleton, a band may have slipped off its leg into the accumulated straw.

You could prise the straw apart over something solid like a boat bottom rather than over water. If instead you do hear a “plop”, be aware they are not magnetic. How do we know this, you ask? From sifting through mud and water around the nest box with a garden sieve until the lost band was finally recovered.

Grey teal females are somewhat easy to catch on their nest to apply bands to and they are not put off by such research.

The bands show they will often come back to the same nest box or a nearby one for the next few years – sometimes twice in one year.

But you will need a DOC permit to catch and band them. However, Z-series (grey teal and shoveler sized) bands are much easier to apply compared

with #27 mallard/grey duck bands.

If you’d like to help band grey teal and/or mallard and grey ducks in the Auckland/Waikato region; contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Some grey teal bands in the past have been recovered in the hunting season when the protected grey teal have been flying in poor light with similar looking grey ducks, for instance. It was not unusual for the hunter to report that “they found a grey teal band”. The important thing is that the information was passed on.

Ducks Unlimited New Zealand started the grey teal nest box scheme, Operation Gretel, around 1974 when the late Jack Worth of Hamilton thought it might be a great way to increase grey teal numbers.

He imported plans of Carolina wood duck nest boxes from the United States and trialled them. The scheme has worked spectacularly ever since.

There is now detailed how-to information online if you too want to play a part making, installing and/or servicing grey teal nest boxes: visit fishandgame.org.nz.

Using game cameras to catch wildlife on film or video is also a fun way of getting new insights into wildlife activity on your pond such as around grey teal nest boxes. But mind the flood levels.

Another lost duck?

Alan Fielding follows up his story on the white-eye duck with that of another duck disappearance – the pink-eared duck.

The pink-eared duck or zebra duck (Malacorhynchus membranaceus), whose Maori name appears to be lost with it, is one of only two genera of the tribe Malacorhynchini, the other being the Salvadori’s duck from New Guinea.

The pink-ear, known in New Zealand from bone fragments of two individuals found by Dr Robert Falla in 1939-41 at Pyramid Valley, north Canterbury, is of geologically recent origin (about 3,500 years), strongly suggesting they are of the Australian species which is widely distributed in inland south-east and south-west Australian and also to a lesser extent in the north-east.

Taxonomical discussions have suggested that the bone fragments may be of a separate species – the so-called Scarlett’s duck – but there remains the doubt.

Pink-ears are a highly nomadic species and their numbers vary greatly depending on the rainfall. Their outstanding mobility makes it easy to see how after a good westerly storm, this country might have been attractive to them. Although the lack of much evidence suggests these birds were vagrants and did not breed here, a stray pink-ear turned up in Auckland in 1990, proving just how mobile the species is.

One thing remains certain: they were self-introduced and therefore indigenous. Their numbers in New Zealand may have escaped suitable preservative sedimentation and they were perhaps more numerous. If this had been during the pre-Maori period,it could explain the loss or non-existence of a name.

Pink-ears are astonishingly quiet, trusting birds which leads one to wonder whether that led to their downfall in colonising New Zealand. These ducks are unmistakable and quite delightful with their distinct zebra stripes and large bill – a bill that is spatulated to a much greater degree than the shovelers and gives them a distinct square-tipped appearance.

Unlike shovelers, the young pink-ears are hatched with the spatulate bill already present along with the distinct “pink ear”, a small pinkish patch slightly behind the eye and difficult to see at a distance. This, as with the zebra stripes, is pale in the juveniles.

The strangely large bill, with its nostrils higher up than usual, is an efficient strainer of tiny organisms such as algae, plankton, insects, crustaceans, and molluscs from the water and mud. This foraging takes place usually without up-ending and never by diving.

Breeding is usually heralded by the sudden invasion of typically shallow, seasonal wetlands (rainfall not exceeding 40mm a year), preferably of long-established origin so that food species populations are high.

The water levels may recede quite rapidly so reproduction needs to be speedy and opportunistic so the nests, typically drowned in down, may be built almost anywhere, often in great density – and might be dispensed with altogether and replaced with “dump laying” even on top of active nests.

If conditions remain suitable, however, they may breed for almost the whole year, with both parents sharing nursery duties. It is thought they may pair for life. Both genders make a chirping, twittering, strange whistling sound, which while soft and deeper in the females and “purring” when communicating with young, can be quite noisy en masse. In flight, these birds utter an unusual trilling sound. Incorrectly believed to be weak fliers, they are quite strong and outstandingly manoeuvrable, extremely gregarious and freely sociable with other waterfowl, notable grey teal.

A highly specialised and successful species, it can inhabit seasonal inland shallow waters, brackish, marine or fresh, through to permanent deeper water and even coastal inlets and mangrove wetlands.

Considering the huge numbers of plant and animal species that have been lost to this country, why not recover what we can, even if it is not endemic?

established several public and private protected areas. He also instigated and coordinated the first National Mangrove Symposium (in Northland) for the Nature Conservation Council.

Good neighbours

ISAAC CONSERVATION AND WILDLIFE PARK CENTRE

A short drive from Christchurch Airport is a 1100-hectare block of land where construction, quarrying, concrete and asphalt companies, livestock and salmon farming co-exist with conservation in a unique business model.

The land is owned by the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust, which was formed in 1977 to continue the conservation work of Sir Neil andLady Isaac, Diana, who had ownedand lived on the land. “Their intention was to leave the place in a better condition than they found it,” says trust administration manager Catherine Ott.

In the early 1950s, Sir Neil and Lady Isaac founded Isaac Construction.

The tagline of combining construction with conservation demonstrates the construction company’s commitment to conservation.

Today the successful construction company is one of the leaseholders on the land which provide the income for the land rehabilitation and conservation activities. Catherine says this business model is really important because it means the trust is self-funding and can exist in perpetuity without the need to fundraise. The assured income also allows planning for the future with confidence.

The main focuses of the trust are the conservation of endangered native flora and fauna, conservation of heritage buildings and the study of conservation through education and research.

Peacock Springs, which covers 73 hectares, is the main conservation area where the endangered NZ species are bred for release into the wild. It is off-limits to the public.

The trust has a memorandum of understanding with the Departmentof Conservation who has requestedthat the trust currently focus on fivebird species – whio (blue duck), pateke (brown teal), black stilt (kaki), orangefronted kakariki and the New Zealand shore plover.

The orange-fronted kakariki numbers were desperately low, Catherine says, and though the DOC put them on predator free islands, they didn’t thrive as well as expected. DOC now release them in the south branch of the Hurunui in the Arthurs Pass region where intensive predator control is undertaken. At the time of writing there are thought to be 200 to 300 orangefronted kakariki alive there, however this population could crash at any time. “We have specialised knowledge

garnered over 20 years in the captive breeding for release. Another reason for our success is because we are not open to the public. The aviaries are not designed for display but for breeding, so you may never see a bird.’’

The kakariki thrive best in dense, dense bush. “Our aviaries are so densely planted, when chicks fledge, it can be very difficult to locate them.”

Catherine says Peacock Springs has also focused on waterfowl and wading birds because it has a good source of water running through the aviaries,

encouraging invertebrates such as water boatman that assist the young birds to learn to forage.

The birds are being bred for release into the wild so some of the aviaries are 7 metres high, allowing the birds such as black stilt to build up strength to fly to escape from predators.

Catherine says that although the public are excluded from most of the conservation activities, an area is open to the public on the easternmost boundary except during lambing and other farming operations. The Isaac Loop track and Isaac Farm Walk are easily accessible from Clearwater Golf Course.

“We have retired a significant portion of land beside the Otukaikino stream and fenced it and planted about 50,000 natives along the loop track. We also have a planting programme across other areas of the Isaac site as part of

our quarry reclamation programme to provide stepping stones for birdlife and invertebrates,” Catherine says.

The trust employs 16 to 20 staff, with more needed during the breeding season. Most are skilled with aviculture experience.

Lady Isaac was not just a wildlife conservationist, but also a conservationist of historic buildings.

The development of the Isaac Heritage Village is based around 14 relocated historic Canterbury buildings. Many of these unique and irreplaceable buildings (c1860 to 1940), were threatened with demolition. The village will eventually be open to the public.

Let’s hit them with some tech

DU Director Dan Steele looks at another tool to help in the fight against predators.

The biggest problem with conservation in New Zealand is complacency and believing that someone else is looking after mother nature on your behalf.

So many people leave things to the Department of Conservation and believe that that’s enough.

It’s not, it’s going to take a huge combined effort from many New Zealanders and particularly landowners to slow the decline in our biodiversity caused by these introduced pests.

But it is not easy to start a conservation project, it is usually an extra job for already busy landowners and who pays, how is it going to be maintained and what should be done?

We ran a really good trapping demonstration for our local sustainable farming group last week, the Taumarunui Sustainable Land Management Group.

Mustelid expert Professor Carolyn (Kim) King, of Waikato University, gave a great overview of New Zealand pests, how we got to this point and whether pest-free New Zealand has any hope of success. The jury is still out on this.

But she believes future technology may well make it possible.

We’re trying to demonstrate that it’s quick and easy to set a few traps around the farm; knowing what to do is often the biggest obstacle with farmers. Then of course there is the capital cost to set up traps and the ongoing maintenance. Goodnature, a Wellington pest company founded 13 years ago, is certainly making the setup and the maintenance easy with their well thought-out technology.

The new Chirp feature on their traps provides bluetooth information from the trap direct to your smartphone.

You link your phone to the trap and it logs the GPS coordinates, and when you check the trap, it tells you how many strikes the trap has had and when.

Then once you’re back into cellphone reception or internet connection, the information is automatically uploaded to the cloud onto the Goodnature world map.

Your traps and kills can be viewed by anyone looking at the map – they show up orange.

Cunningly though, when people are viewing your traplines, they can only see to within 150 metres of where you have your traps placed, so people can’t turn up and steal or sabotage your traps. The owner of the traps can however have their GPS coordinates down to a metre or two.

We are finding the A24 Goodnature traps a good way for people to sponsor some traps, to be involved and stay in touch with how the conservation work

is performing.

It’s so important to be holding our ground against predators; this week at Blue Duck Station, we have had a kaka sighting and a report of a bittern booming.

The Goodnature A24 rat and stoat trap automatically kills 24 rats or stoats (and mice) one after the other, before you need to replace the CO2 gas canister. When the pest tries to reach the lure inside the trap, they brush past a trigger which fires a piston, killing them instantly. The piston retracts and resets ready for the next pest. The trap comes with a pump that refreshes the lure automatically for six months. Three different trap kits are available: a trap-only kit, a trap with a counter or a trap with Chirp.

World Wetlands Day events

The 2020 Puweto Festival honoured the day at Lake Rotopiko, which DU visited during its 2018 conference in Hamilton. Wetland bird masks, a critter colour-in, mudfish scrabble, eels and ladders, live geckos, kahikatea tree climbing and a virtual reality lake dive were among the offerings for families who attended.

The event was named after the shy puweto/spotless crake that lives around the margins of the lake.

Rotopiko is being developed into a National Wetland Centre, with newly completed boardwalks, information panels and an interactive discovery trail. During the festival, Treelands (local arborists) climbed up kahikatea to install bat roost boxes – something they have been doing all over the region. Other activities around the country included a guided walk at Harbourview-Orangihina Park in Te Atatu on 1 February and Matuku Reserve Trust in West Auckland had an open day to show off its wetland restoration and give the public a chance to see pateke.

In Wellington, Zealandia visitors were able to talk to experts from organisations including the Hakuturi Roopu, Greater Wellington Regional Council and Lakes380 to learn more about freshwater and wetlands in New Zealand.

In Marlborough, visitors were invited to check out a community-led wetland restoration project and walk around the Grovetown Lagoon. A guided walk was held around the Travis wetland in Christchurch.

The QEII National Trust took the opportunity on World Wetlands Day to introduce a new QEII wetland covenant to protect the Galloway Wetlands in Ashburton.

The trust said: “Craig and Lyn Galloway bought their farm in 1986 on the south bank of the North Branch of the Ashburton River. When they purchased the property, all paddocks had been developed except for the wetland paddock which remained uncultivated.

“Craig and Lyn applied to the Ashburton Water Zone committee for a grant to expand their successful riparian planting programme to the margin of a stream and man-made pond.

“Spring-fed channel wetlands like theirs have virtually disappeared elsewhere on the Canterbury Plains. They decided to place a covenant over the whole

6-hectare wetland complex to preserve the relict pre-human vegetation.

“The covenant is a rare example of the highly diverse wetland complex and landform created by hydrologically connected springs associated with braided rivers. The wetland ecotone contains a spring-fed mossy fen, bog rush channel wetland, stream, manmade ponds, pukio and kiokio fern swamp, and toetoe marsh.

“The Galloway Wetlands protect the only known manuka, sphagnum moss and the pink-flowered wetland ladies tresses orchid (Spiranthes novae-zelandiae) on the Ashburton Plains.” Matagouri and the rhizomatous shrubby violet known as a porcupine shrub have survived on the stony ridges in the covenant but both are rarely encountered elsewhere in the region, the QEII Trust said.

The landowners plan to supplement these species with new plants, grown from seed sourced from the local area. This covenant is one of very few

that meet all four national priorities for protecting rare and threatened biodiversity on private land.

But it was not all good news for wetlands. In a statement released to mark World Wetlands Day, Forest and Bird said West Coast landowners had wiped out more wetlands in the past 20 years than landowners in any other region. Aerial images from around the country supplied by Landcare Research showed that wetlands on private land were still disappearing at an alarming rate.

The West Coast was the largest wetland region in New Zealand, with nearly 84,000 hectares of freshwater wetlands, 14 per cent of them in private ownership, Forest and Bird said.