Tracking wetland changes through eDNA

A study has shown that environmental DNA, known as eDNA, may be valuable in measuring biological changes in wetlands. The eDNA is extracted from soils, air, water, and other substrates.

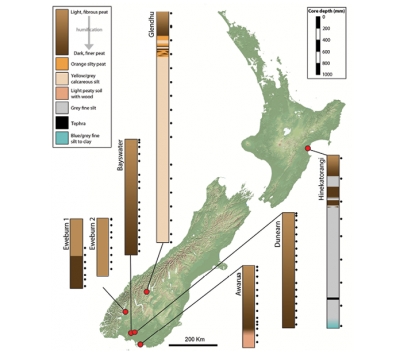

Researchers from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research sequenced microbial DNA from soil cores taken down to 4 metres below the surface in seven New Zealand wetlands in one of the few studies globally to have studied wetland microbes at such depths.

“The results showed distinct changes in microbial communities as we went deeper,” says study co-author Dr Olivia Burge.

Biodiversity monitoring in wetlands tends to focus on large organisms such as birds and plants, which can be relatively slow to respond to environmental change.

Lead author Jamie Wood says the strength of eDNA is that it allows researchers to study microbial groups (bacteria and archaea), which may respond faster to environmental change.

As a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission. This is

a process driven by microbes, and the researchers saw an increase in the types of microbes responsible in the upper

layers of the more modified wetlands.

“An unexpected finding was that the effects of drainage also appeared at greater depths, below the water table, where the relative proportion of microbes responsible for carbon fixation and methane generation decreased,” he says. As part of the study, the researchers compared three similar wetlands with different degrees of human modification. When a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission.

“Ultimately eDNA may provide a useful tool for monitoring real-time wetland condition and identifying when critical thresholds are being approached,” says study co-author Beverley Clarkson.