Displaying items by tag: Wetlands

Wetland restoration under the microscope

Restored wetlands on private farms deliver ecosystem services and increase diversity, with varied results, a recent study has found. Shannon Bentley, a master’s student at Victoria University and the first recipient of a Wetland Care Scholarship funded by Ducks Unlimited NZ, is studying how wetland restoration on farms changes plant, soil, and microbial characteristics. In 2018-2019, as a part of the research group, Wetlands for People and Place, she sampled 18 privately restored wetlands and paired unrestored wetlands on farms in the Wairarapa.

For her master’s thesis, she analysed the wetland plant communities, soil physiochemical characteristics, and soil microbial communities to understand how they change with restoration. She found that wetland restoration on private property shifts plant, soil, and microbial characteristics towards desirable remnant wetland conditions. She also showed that the outcomes of wetland restoration varied within and between wetlands.

More than 40 per cent of New Zealand is held in private ownership, and private property holds huge potential for wetland restoration, containing 259,000km of stream length (Daigneault, Eppink, & Lee, 2017). Additionally, wetland degradation is extensive in lowland environments which are primarily in private ownership.

The outcomes of wetland restoration undertaken by landowners’ own prerogatives are poorly tracked. Private restoration is driven by personal preferences and finances, so the extent and form of restoration are varied. For example, the 18 wetlands sampled in Shannon’s study were restored in many different contexts and using many different techniques.

Wetlands differed in time since initial restoration (6 months to 42 years ago), size (0.4ha to 33.7ha), upstream watershed area (4ha to 2,263ha), dominant plant community (woody v herbaceous), and the number of restoration techniques used (2 to 8).Wetland restoration is beneficial for a number of reasons, but particularly for regaining wetland ecosystem services and increasing native biodiversity. Ecosystem services are ecological processes and functions that have beneficial outcomes for humans.

Compared with all other ecosystems, wetlands produce the highest levels of ecosystem services per unit area. This high production of ecosystem services is due to wetlands’ unique biology and geology resulting from their position at the interface of water and land. Wetlands are particularly effective at producing the ecosystem services of water purification, flood abatement and climate regulation through carbon sequestration.

Shannon found that with restoration, soils regained wetland traits, providing more ecosystem services. The restored soils had higher carbon content, lower bulk density, and lower plant-available phosphorous. Increased soil carbon content shows the carbon sequestration potential of soil expands with restoration.

Additionally, reduced plant-available phosphorous indicates restored wetlands can take up phosphorous and improve downstream water quality.

And finally, with increased carbon and reduced bulk density, water moves through the wetland soils slower to reduce peak flood heights.

Shannon found wetland soil microbes increased in biomass and fungal dominance after restoration. These changes, in part, explained the increase in capacity for wetlands to deliver ecosystem services.

Soil microbes are responsible for decomposition and nutrient cycling. A greater mass of microbes means restored wetlands have more capacity for biogeochemical cycling and decomposition, which can accelerate processes such as carbon burial, as

seen with the increased carbon in restored wetland soils compared with unrestored soils.

The presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) also increased after restoration. AMF help plants survive and reduce phosphorous in soils, thus contributing to cleaner waterways.

Each restored wetland showed a lot of variability of soil and microbial responses within and across wetlands. Because wetlands are found along a hydrological gradient between saturated soils and drier, upland soils, the microbial and soil properties differed according to the landscape position.

Soils close to the water’s edge, as a result of being saturated, had more carbon, microbial biomass, and more fungal biomass, and were less dense. By examining the plant communities, Shannon found that, after restoration, plant diversity increased within the plot and across the landscape. This means that with restoration, habitat heterogeneity increases, a beneficial outcome that increases ecosystem stability and the number of ecosystem services produced.

Additionally, she found that wetland soils and plant and microbial communities showed different levels of recovery that were not consistent with the length of time that they had been restored.

Some projects’ soil and microbial characteristics recovered faster than others. The main difference between fast and slower-recovery wetlands was the hydrological regime.

Restoration projects that occurred on isolated hydrological systems such as depressional, rainwater-fed wetlands took far longer to re-establish remnant wetland conditions. Projects undertaken on flowing hydrological systems such as springs and streams underwent successional processes faster to establish wetland conditions that have a higher production of ecosystem services.

The study has shown that restoring wetlands on private farms increases the ecosystem’s ability to simultaneously produce multiple different ecosystem services and support more biodiversity.

As food production demands continue to rise simultaneously as land becomes more scarce, agricultural systems are becoming more industrialised and intensive. This is placing pressure on natural ecosystems, as seen by reduced water quality, native habitat, and changing landscapes from carbon sinks to sources.

There is increasing recognition that we need mixed agroecosystems so food production does not compromise other ecosystem services.

Wetland restoration is gaining significant traction as a solution to issues surrounding water quality, climate regulation, flooding, and loss of native habitat, and this study has shown that private restoration is effective tool to do just this.

Shannon concludes her report by saying: “I would like to thank all the landowners that generously allowed us to sample their wetlands; each site we visited was so beautiful and unique.

“I thank Ducks Unlimited for the funding that allowed me to do this research. I also thank the Holdsworth Foundation, the Sir Hugh Kawharu Foundation, Wairarapa Moana Trust, and Victoria University for the financial support I have received.

“Finally, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr Julie Deslippe and Dr Stephanie Tomscha for their guidance and help in producing this research.”

Spectacular Rakatu

With international travel off the agenda for now, it may be time to check out some of New Zealand’s public-access wetlands.

One such gem can be found on the Southern Scenic Highway between Manapouri and Tuatapere.

If you are heading south from Manapouri, take a right after the sign for Rakatu Wetlands and at the end of a 1km gravel road, there’s a car park with information boards.

There are four main walks, from 15 minutes long to two to three hours. It’s a spectacular setting with Fiordland National Park as its western backdrop, and no less impressive are the flush toilets up the track to the lookout. Complete with toilet paper and soap, they are an unexpected bonus to visitors expecting the usual pongy long drop.

The 270-hectare wetland complex was created for the benefit of fish and waterfowl as well as protected bird species to mitigate and remedy the adverse effects of the Manapouri Hydroelectric Power Scheme.

It is administered by the Waiau Fisheries and Wildlife Habitat Enhancement Trust.

Rare carnivorous plant found

A seldom-seen carnivorous species has been found during a survey of rare plants at Waikato’s Whangamarino Wetland.

It’s been more than a decade since threatened plants have been surveyed at Whangamarino Wetland, with the last survey in 2009.

Waikato District biodiversity rangers Lizzie Sharp and Kerry Jones, and plant expert Britta Deichmann waded into the boggy wetland for 12 days between September 2020 and April this year.

“We were particularly excited when we found Utricularia australis or yellow bladderwort, an aquatic carnivorous plant,” Lizzie Sharp said.

“We had several ID books out and a lively debate about whether it was yellow bladderwort or the invasive weed Utricularia gibba or humped bladderwort.”

The difference between the two plant species is the number of divisions in the

leaves, and closer inspection revealed it was yellow bladderwort, which is known only in the North Island.

“Yellow bladderwort was found at one site in the 2009 survey, and prior to that, at 11 sites based on historic data.

“By 2009, 10 of those sites had been infested with humped bladderwort, and as more than 10 years have passed since that survey, we expected the worst ...”

The bog in the Whangamarino Wetland is treacherous so visits by the public are discouraged. There are no tracks into the swamp, but people are permitted on the Maramarua and Whangamarino rivers and Reao Stream.

For more information about Whangamarino Wetland and its biodiversity, visit: www.doc.govt.nz/our-work/freshwater-restoration.

A long road that doesn’t have a turn in it

Farmer and conservationist Russell Langdon is philosophical about the recent flooding that swept through his property.

Russell Langdon, 89, has had his share of challenges at the wetland reserve he has established on his farm in Mid-Canterbury, near the South Branch of the Ashburton River.

The May floods were the latest hurdle. “The river broke out and came right through here. It flattened a few fences and damaged aviaries, but it’s nothing we can’t handle. The birds survived all right.”

He said the clean-up at Riverbridge, however, would take a long time. Riverbridge Conservation Park is an 8.3ha wetland habitat with half-a-dozen ponds and enclosures for native wildlife on Russell’s farm at Lagmhor, near Westerfield, southwest of Ashburton.

Among the birds he breeds are brown teal/pāteke and kākāriki. He used to breed whio but a freak snowstorm in 2010 put paid to that.

The whio enclosure was destroyed and the ducks were gone. The Department of Conservation removed Riverbridge from the whio breeding programme, and now it says Orana Wildlife Park and the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust fulfils the requirements.

Russell has had plenty of run-ins with bureaucrats over the years – “they weren’t raised under a hen like me” but he takes it all in his stride. As he says, “It’s a long road that doesn’t have a turn in it”.

His land sits on top of an old river bed and the natural water level lies only a metre or so down, making it ideal wetland country. The land slopes east towards the sea “about 30 feet to the mile” so if you dig down and plug up both the eastern and western sides of the hole, a pond will form naturally. Russell grew up on a farm at Westerfield that his father bought after World War one, and so he only moved a short distance when he bought his farm at Lagmhor 40 years ago “when sheep were king”.

Russell’s stock numbers soon grew from 800 to 4000 and, along with a stint in the farm machinery business which involved a lot of travelling, selling mainly Case headers, he led a busy life. Riverbridge was just farm paddocks when Russell started transforming it into a habitat for waterfowl and other birds. It is now a fully formed wetland with ponds and native forest, mostly unplanned and planted to encourage wildlife to thrive.

Russell says his family were all great tree planters and he has planted 1000s of trees over the years.

Riverbridge started taking shape 21 years ago when Russell planted trees as a millennium project. “We made a lot of mistakes but who hasn’t.”

Among the trees on the property are matai, kahikatea, totara, cabbage trees, olearia, coprosmas, flax, kowhai and lacebark.

He says he still has a lot more trees to plant, with a hand from his brother John, two years his junior.

Just inside the entrance to Riverbridge is the old Westerfield schoolmaster’s house, built in 1888. Russell bought it in 1964 and relocated it to host school groups and tourists.

At the time, DUNZ had a South Island chapter, and Russell had had plans to use it as accommodation for DU members and other groups.

The walls are lined with information about wetlands, posters on endangered species and newspaper clippings about the park.

The wetlands start and stop in the property, so there’s no predatory trout, making it a safe environment for the critically endangered Canterbury mudfish.

Russell also has plans to introduce freshwater crayfish/koura into the wetland. The biggest pond is quite shallow, making it ideal for wading birds including pied stilts, spoonbills, and scaups and shovelers are also happy there. There’s marsh crakes too but they are hard to spot, and some buff weka.

Sharing the kākāriki enclosure at Riverbridge are a pair of Reeves’s pheasants though the male needs to be moved and Russell is not looking forward to that task. “If you go in there, he takes to you,” he says.

The lower part of the pāteke enclosure is covered in aluminium mesh which allows bugs in, but no predators.

The park is protected by a QEII convenant and it receives funding through grants applied for through the Riverbridge Native Species Trust. These days, Russell, who was awarded a QSM in 2006 for his services to conservation, says he potters around Riverbridge, leaving the farming to his nephew – and for now his focus is on cleaning up after the floods.

Wairio on show

About 30 people braved squally rain on Sunday, May 9, for a guided tour of Wairio Wetland led by Ducks Unlimited NZ President Ross Cottle and Director Jim Law.

The event was a Rural Women New Zealand annual event to raise money for the Associated Country Women of the World to help fund community projects in developing countries.

Before setting out, Ross and Jim told the visitors about DU’s long involvement with the wetland – from Stage 1, its initial project about 17 years ago through to the latest development in Stage 4.

Ross said the wetland’s only water source in 2005 was courtesy of high wind dumping water into it from Lake Wairarapa to the west, but it didn’t retain it, and the water flowed straight back into the lake.

DU put in a bund wall, which was moderately successful, holding the water through the bird breeding season, but by December, it had dried out.

The next step was to dig down to a lower level to keep the water there longer, which was more successful, holding the water till the birds had bred and fledged. At the same time, DU planted out native species and these are now well established in Stage 1.

From there, it was on to Stage 2 and 3, and every low spot was fenced off with a bund wall.

Stage 3 was handed over to Victoria University because “we wanted some science behind it”, Ross said. It was envisaged that the project would provide a template for wetland restoration.

“Next thing, someone had a bright idea to put in a bund wall” between the three stages and the lake. About two weeks later, a mighty wind blew water in from the lake and “we had 100 acres of water”. After that success, DU extended the bund all the way back to Stage 1.

This was “amazingly successful” and has created a wetland of more than 250 acres of water.

“We were successful beyond our wildest dreams,” Ross said.

Jim said Wairio had been a ground- breaking project, with the Department of Conservation handing over the wetland’s management to DU – at the time it was unheard of for DOC to hand over restoration of its land to a local group.

“It only took us two years to convince DOC to let us spend our money on their land.”

DU has spent more than $200,000 in the past 17 years. About half of this has come from donations, which began rolling in once people saw how Wairio was being transformed and the return of wildlife.

On the 4.2km walk, Jim led the visitors along the bund wall track through Stage 4 of the wetland, where he described DU’s vision of the future – when stands of kahikatea would replace the current open areas of fescue.

With a rainbow in the background, and Ross bringing up the rear in his side-by-side to assist any stragglers, the tour covered Stages 3 and 2 before reaching its conclusion at Stage 1.

On a small detour from the main track to the water’s edge at Stage 4, the group had a preview of the proposed site for a viewing hide which DU has built. It is now waiting for a resource consent to place it on the site.

Birdlife has flourished at Wairio since DU took over, and the number of royal spoonbills, which previously had not been seen for 30 years, have surpassed 100, and they are breeding there.

Bittern numbers have remained stable in the past four or five years, despite a continuing decline throughout the rest of New Zealand.

Over a hot cuppa back at the cars, the visitors said the tour had been a revelation and they were highly impressed with their tour guides’ continuing passion and enthusiasm for the project.

Tracking wetland changes through eDNA

A study has shown that environmental DNA, known as eDNA, may be valuable in measuring biological changes in wetlands. The eDNA is extracted from soils, air, water, and other substrates.

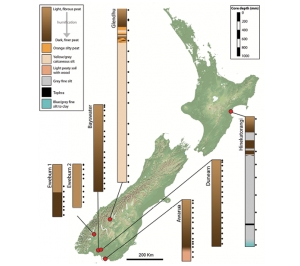

Researchers from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research sequenced microbial DNA from soil cores taken down to 4 metres below the surface in seven New Zealand wetlands in one of the few studies globally to have studied wetland microbes at such depths.

“The results showed distinct changes in microbial communities as we went deeper,” says study co-author Dr Olivia Burge.

Biodiversity monitoring in wetlands tends to focus on large organisms such as birds and plants, which can be relatively slow to respond to environmental change.

Lead author Jamie Wood says the strength of eDNA is that it allows researchers to study microbial groups (bacteria and archaea), which may respond faster to environmental change.

As a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission. This is

a process driven by microbes, and the researchers saw an increase in the types of microbes responsible in the upper

layers of the more modified wetlands.

“An unexpected finding was that the effects of drainage also appeared at greater depths, below the water table, where the relative proportion of microbes responsible for carbon fixation and methane generation decreased,” he says. As part of the study, the researchers compared three similar wetlands with different degrees of human modification. When a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission.

“Ultimately eDNA may provide a useful tool for monitoring real-time wetland condition and identifying when critical thresholds are being approached,” says study co-author Beverley Clarkson.

Restored wetlands bring diversity

DU's inaugural scholarship recipient Shannon Bentley is in the final stages of analysing data for her thesis on wetland restoration.

She says she is exploring how restoring wetlands from pasture changes plants, microbes and soil.

"Restored wetlands are home to more diverse native plant communities and soil microbial communities than pastures, preliminary results show.

"This diversity produces a wide variety of benefits for people. For example, restored wetland soils have an increased capacity to store carbon, attenuate floods, and remove excess nutrients. "However, restoration creates a wide variety of responses, with every restored wetland being different."

More to come from this space, she says.

Takitakitoa impresses trustees

"The best bang for your buck" is how New Zealand Game Bird Habitat

Trust Chair Andy Tannock described Takitakitoa Wetland in Otago on September 19.

Trustees visited the wetland near the Taieri River during the annual meeting of the trust which was held in Dunedin.

It was the first meeting of the new board appointed by the Minister of Conservation in July. It consists of Andy Tannock, DU Board member Neil Candy, former DU president John Cheyne, Jan Riddell, Mark Sutton and Chantal Whitby.

The trust met to review 14 applications made to the trust for wetland projects across the country for 2020 – they subsequently approved 11 of the applications.

The award-winning Takitakitoa project has previously received funding from the trust.

Takitakitoa has been one of the largest wetland enhancement projects undertaken without extra funding help from non-Fish & Game sources. Otago Fish & Game was gifted the lower portion of the wetland in 1994, around 40 hectares, and later obtained the upper portion of the 70ha wetland, through a land swap deal.

The project was launched with a $50,000 grant from the Game Bird Habitat Trust which was largely spent on constructing a 350-metre bund so the valley floor,

which was drained in the 1960s, could be reflooded. This took about two years to complete. Otago Fish & Game Council also put funds into the project.

"It was basically taking 32 hectares of drained, failed farmland and turning it back into wetland," says Otago Fish & Game chief executive Ian Hadland. "Takitakitoa is a shining example of hunter funding being used for greater conservation benefit.

This is an ecological restoration project which has benefits for not just duck hunters, but anyone interested in enhancing or conserving natural habitat for the future."

As soon as water refilled the wetland, all sorts of wildlife turned up, species that had not been previously observed there while it was in its degraded state, he says. "There’s clearly conservation benefits there that even I didn’t expect. Some creatures turned up that I didn’t even know were in the neighbourhood … like the pied stilts. There are probably 30 to 50 that have moved in to live and raise their chicks."

Wildlife included species well outside of Fish & Game’s area of interest such as inanga (whitebait), fernbirds, grey teal and royal spoonbills.

However, Ian points out that mallard ducks and some other game birds have also colonised the area, and allowed for the wetland to be used for novice hunting in particular.

"Getting the next generation of hunters out there to appreciate wetlands and learn their value is important. Those young hunters will undoubtedly fund similar conservation efforts in the future." Takitakitoa is a project that Fish & Game can hold up as "a great example of a duck hunter-funded conservation project", he says.

For more about the wetland and how to apply for Game Bird Habitat Trust funding, go to: youtube.com/watch?v=JtpRBbp6t1w.

In December the Game Bird Habitat Trust was granted $360,000 over three years through the Government's One Billion Trees project.

The money will be used to establish plantings on projects that the trust

supports around New Zealand.

Trust chair Andy Tannock says this is a significant boost for wetland habitat projects and complements the trust’s goals.

Andy says the trust will be working on setting up a process to support the planting of natives such as flaxes and woody species at sites that have received the trust's funding support. Many of the projects are on private land.

Andy acknowledges the work of Dr Matt Kavermann, the senior fish and game

officer for Wellington Fish and Game Council who worked with the Ministry for Primary Industries to establish the grant.

A pond for pateke

Te Henga wetland, which covers 160 hectares and is the biggest in Auckland, has the potential to be the ideal wildlife habitat with acres of reeds, raupō, sedges, open water ponds and the Waitākere River coursing through it.

Forest & Bird’s project Habitat te Henga was born from a desire to protect the

wetland. It started in 2014 with intensive stoat control, using 100 DOC 200 traps, several A24s and some cat traps.

Two trap lines totalling 30 kilometres were regularly checked and reset by a dedicated trapper. Scores of DOC 200s and A24s have been added since.

Effective predator control was required before translocation of pāteke could be considered and the first contingent of 20 pāteke was released in 2015, with a survival rate of 80 per cent, leading to another release of 80 birds in 2016. This has been covered previously in Flight magazine.

This success brought us closer to that ideal habitat and aroused interest and support from the local community and a range of other organisations.

Matuku Reserve Trust Board was established when the last block of bush and wetland came up for sale. The trust was able to buy it in November 2016.

The property, at the head of the Te Henga wetland in West Auckland, has raupō

and sedge beds, and open water ponds along the meanders of the former course of the river.

There are remnant pukatea and kahikatea at the foot of mixed kauri-podocarp-broadleaf forest from which small streams and seeps enter the flats.

With several other conservation projects including the Ark in the Park, Habitat

te Henga, and Forest & Bird’s Matuku Reserve alongside it, the 37-hectare property has been named Matuku Link. Here, a nursery has been established providing most of the plants that are converting the kikuyu-covered flood plain into a range of wetland habitats. An old barn has been transformed and provides not only a volunteer base but already does duty as a site for wetland education to the many school, service, business, and community groups that help with planting and bird releases. An aim is to have an on-site educator to work with schools.

Dozens of local residents have become involved as part of a buffer zone, collecting their traps or bait from the barn and local interest is really heightened when, as has happened in the past two years, pāteke have bred in their ponds or streams.

Also exciting for our neighbouring conservation group to the north was their discovery last year of a pāteke pair that had dispersed several kilometres into the forest-clad stream that disgorges into the te Henga wetland.

New ponds have been constructed at Matuku Link, with one of them sporting a family of seven pāteke ducklings. A more established pair on an existing pond are

so placid and accommodating that almost all visitors get to see them plus or minus their ducklings.

A further new pond was part of a survey for a PhD study on ponds and sampling from its inception over the year showed that it only took five to six months until

the Macroinvertebrate Community Index (MCI) matched that of established ponds. The MCI measures water quality.

Measuring outcomes for wildlife with predator control in place has involved

biennial audio recordings for matuku and pūweto. Pūweto are also surveyed annually. Goodnature A24 traps were deployed 18 months ago between an

existing DOC 200 array to see if a benefit to wildlife could be shown using pūweto as an indicator species.

The DOC 200 traps have been in place for six years and with the recording of fortnightly trap catch data and sightings or detections of matuku [bittern], pūweto [crake] or pāteke, we have a basis to see if change is detectable.

Rodent monitoring is undertaken three times a year by Auckland Zoo staff as part of its Conservation Fund outreach.

Native freshwater fish present include both long finned and short finned tuna, and one stream surveyed also had Cran’s bully, common bully, banded kōkopu and an unidentified galaxiid. These surveys have been done by Whitebait Connection which has also tested water quality parameters. Testing showed high health

of the river and streams.

A second forest-covered stream surveyed showed only eels and kōura but the

presence of a large overhanging culvert is the likely cause of the difference. With Whitebait Connection’s help, a fish ladder has been constructed and followed by

repeat surveying.

At other sites, galaxiids have wasted no time in colonising upstream once

impediments are removed and we also trapped a banded kōkopu upstream of

the culvert within a fortnight.

As well as continuing to use G-minnow traps, we will be taking water samples

to test for eDNA (environmental DNA). Multi-species testing of DNA in the

water will show what fish we have but it is also possible our streams have Hochstetter’s frog and Latia, the native limpet [the world’s only mollusc with bioluminescence].

The rest of the wetland is privately owned, but access to see wetland

habitats is now possible at Matuku Link. River flats make for easy walking but

accessibility for wheelchairs and buggies is being enhanced with good surfaces

and our first boardwalk has its official opening at our World Wetlands Day event in February 2021.

Building this boardwalk and other infrastructure was made possible by the post-Covid Jobs for Nature scheme. Our World Wetlands Day event is one of two open days we usually hold each year but now the barn is finally renovated, we

expect to open more frequently.

The annual kayak trip down the river offers visitors an intimate view of a large healthy wetland as well as being a great fundraising event. This year the event

will be on Saturday, April 27.

Our newest pond, made possible by Ducks Unlimited NZ, is slowly filling and once the plantings are established, we look forward to seeing pāteke and other wetland birds using it.

For more information, visit www.matukulink.org.nz and www.facebook.com/matukulink.

Mission impossible

Contractors wildlife expert Sandy Bull and Ecoworks' Steve Sawyer bring birdlife into Nick's Head Station and look after the 2-metres-high predator-proof fence, which protects 35 hectares of native bush and a wide array of wildlife.

About 60 tuatara were translocated from Stephens Island in Marlborough Sounds, and now, safe within the fence, their numbers have grown to more than 100.

There are also about 180 nesting gannets, about 55 to 60 grey-faced petrels, sooty and fluttering shearwaters and even an arctic skua has been seen within the fence.

"Initially, they said we couldn't do it," Sandy says.

To attract the seabirds, Steve smothered the rocks with white paint to look like guano and installed a sound system to replicate the calls of various seabirds. The gannets have been nesting there for several years now.

Sandy says there are plans to translocate saddlebacks and giant weta. He has also been involved in translocating pāteke to the wetland and about 200 have been released. He says they are now moving around the region and another survey of bird numbers is due but it is clear the pāteke are doing well.

Sandy told DU members that he was well aware of the wealth of knowledge within DU and members' involvement with wetlands around New Zealand.

He says Gisborne is desperately short of wetlands. The biggest is Lake Repongaere, covering about 110 acres. "There are farm ponds all over Gisborne attracting wildlife but we are very short of big wetlands. This one [at Nick's Head Station] is a joy to behold."

Some of the visiting and resident birds:

- pukeko – numerous (some have been culled);

- paradise shelducks;

- shags – black, pied, little, little black and kawau;

- white faced herons; bittern – though they are seldom seen;

- pied stilts;

- kōtuku;

- royal spoonbills;

- godwits – spotted recently;

- a nesting colony of black billed gulls, the world's rarest gull;

- black-fronted terns – spotted once; dab chicks;

- NZ scaups – in low numbers;

- graylards – interbred with mallards and grey teal;

- grey teals;

- shovelers;

- Canada geese; penguins – a colony on the beach;

- oystercatchers; pāteke;

- gannets;

- petrels;

- Arctic skuas;

- fluttering shearwaters;

- sooty shearwaters