Displaying items by tag: Pateke

A pond for pateke

Te Henga wetland, which covers 160 hectares and is the biggest in Auckland, has the potential to be the ideal wildlife habitat with acres of reeds, raupō, sedges, open water ponds and the Waitākere River coursing through it.

Forest & Bird’s project Habitat te Henga was born from a desire to protect the

wetland. It started in 2014 with intensive stoat control, using 100 DOC 200 traps, several A24s and some cat traps.

Two trap lines totalling 30 kilometres were regularly checked and reset by a dedicated trapper. Scores of DOC 200s and A24s have been added since.

Effective predator control was required before translocation of pāteke could be considered and the first contingent of 20 pāteke was released in 2015, with a survival rate of 80 per cent, leading to another release of 80 birds in 2016. This has been covered previously in Flight magazine.

This success brought us closer to that ideal habitat and aroused interest and support from the local community and a range of other organisations.

Matuku Reserve Trust Board was established when the last block of bush and wetland came up for sale. The trust was able to buy it in November 2016.

The property, at the head of the Te Henga wetland in West Auckland, has raupō

and sedge beds, and open water ponds along the meanders of the former course of the river.

There are remnant pukatea and kahikatea at the foot of mixed kauri-podocarp-broadleaf forest from which small streams and seeps enter the flats.

With several other conservation projects including the Ark in the Park, Habitat

te Henga, and Forest & Bird’s Matuku Reserve alongside it, the 37-hectare property has been named Matuku Link. Here, a nursery has been established providing most of the plants that are converting the kikuyu-covered flood plain into a range of wetland habitats. An old barn has been transformed and provides not only a volunteer base but already does duty as a site for wetland education to the many school, service, business, and community groups that help with planting and bird releases. An aim is to have an on-site educator to work with schools.

Dozens of local residents have become involved as part of a buffer zone, collecting their traps or bait from the barn and local interest is really heightened when, as has happened in the past two years, pāteke have bred in their ponds or streams.

Also exciting for our neighbouring conservation group to the north was their discovery last year of a pāteke pair that had dispersed several kilometres into the forest-clad stream that disgorges into the te Henga wetland.

New ponds have been constructed at Matuku Link, with one of them sporting a family of seven pāteke ducklings. A more established pair on an existing pond are

so placid and accommodating that almost all visitors get to see them plus or minus their ducklings.

A further new pond was part of a survey for a PhD study on ponds and sampling from its inception over the year showed that it only took five to six months until

the Macroinvertebrate Community Index (MCI) matched that of established ponds. The MCI measures water quality.

Measuring outcomes for wildlife with predator control in place has involved

biennial audio recordings for matuku and pūweto. Pūweto are also surveyed annually. Goodnature A24 traps were deployed 18 months ago between an

existing DOC 200 array to see if a benefit to wildlife could be shown using pūweto as an indicator species.

The DOC 200 traps have been in place for six years and with the recording of fortnightly trap catch data and sightings or detections of matuku [bittern], pūweto [crake] or pāteke, we have a basis to see if change is detectable.

Rodent monitoring is undertaken three times a year by Auckland Zoo staff as part of its Conservation Fund outreach.

Native freshwater fish present include both long finned and short finned tuna, and one stream surveyed also had Cran’s bully, common bully, banded kōkopu and an unidentified galaxiid. These surveys have been done by Whitebait Connection which has also tested water quality parameters. Testing showed high health

of the river and streams.

A second forest-covered stream surveyed showed only eels and kōura but the

presence of a large overhanging culvert is the likely cause of the difference. With Whitebait Connection’s help, a fish ladder has been constructed and followed by

repeat surveying.

At other sites, galaxiids have wasted no time in colonising upstream once

impediments are removed and we also trapped a banded kōkopu upstream of

the culvert within a fortnight.

As well as continuing to use G-minnow traps, we will be taking water samples

to test for eDNA (environmental DNA). Multi-species testing of DNA in the

water will show what fish we have but it is also possible our streams have Hochstetter’s frog and Latia, the native limpet [the world’s only mollusc with bioluminescence].

The rest of the wetland is privately owned, but access to see wetland

habitats is now possible at Matuku Link. River flats make for easy walking but

accessibility for wheelchairs and buggies is being enhanced with good surfaces

and our first boardwalk has its official opening at our World Wetlands Day event in February 2021.

Building this boardwalk and other infrastructure was made possible by the post-Covid Jobs for Nature scheme. Our World Wetlands Day event is one of two open days we usually hold each year but now the barn is finally renovated, we

expect to open more frequently.

The annual kayak trip down the river offers visitors an intimate view of a large healthy wetland as well as being a great fundraising event. This year the event

will be on Saturday, April 27.

Our newest pond, made possible by Ducks Unlimited NZ, is slowly filling and once the plantings are established, we look forward to seeing pāteke and other wetland birds using it.

For more information, visit www.matukulink.org.nz and www.facebook.com/matukulink.

Report on Operation Pateke (Brown Teal)

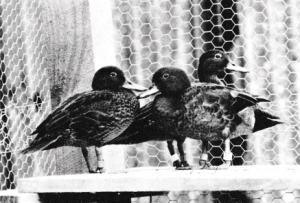

Mr F.N. Hayes outlined the year's highlights - among them the first official recording of captive reared Brown Teal in the wild on the mainland; and the outstanding figure of 101 birds reared to maturity by DU members — expressing thanks to all concerned and particularly the N.Z. Wildlife Service and Messrs J. Gill, 5- Bronger, J. Campbell, J. Glover and W. Clinton—Baker. of the 101 birds reared, 64 were released on Matakana Island, 22 were retained for flock mating and 15 kept fcrrelease in August at Puke Puke Lagoon. Including the 25 birds reared by the N.z. Wildlife Service, Brown Teal reared in New Zealand last breeding season numbered approximately ten per cent of the estimated world population.

In the United Kingdom the Wildfowl Trust has reared 30 birds in the two seasons since Ducks Unlimited sent two females for its collection. It would be some time before the target of 50 breeding pair would be reached but the group was confident this figure would be achieved. The objective for the coming year was 40 pair held by 20 Ducks Unlimited members.

Mr Hayes advised that the Wildlife Service had paid Ducks Unlimited $ 5 for each bird released to the wild - this was passed to breeder members, together with a further $ 5 as a token reimbursement of cost for rearing to maturity. Favourable comments had been received concerning the Brown Teal booklet produced following the Brown Teal seminar in 1980 and thanks expressed to Mrs C.L. Pirani for assistance with production and Dr M. Williams of the Wildlife Service for technical assistance.

Mr Hayes concluded by stating Ducks Unlimited was confident the current season's record would be exceeded in the coming year and that the group was searching for further release sites. He answered questions concerning publicity on television and in scientific journals; population levels; fundraising for the project and stated that the aim was to maintain a stable population level for Brown Teal in the years ahead.

Report

Brown Teal released at Puke Puke Lagoon:

On 9 August 1981 DU released 12 Brown Teal at Puke Puke Lagoon, Foxton — 8 females and 4 males. This is the first time DU has released birds at this time of year and the resident Wildlife Service technician at Puke Puke Lagoon will be keeping a close watch to see how the birds adapt. All 12 birds were those reared towards the end of last breeding season, too late for release during last summer. Thanks to Mr J. Glover for holding most of the birds during the winter. The latest release brings to 76 the number of Brown Teal released during 1981.

Brown Teal at the Wildfowl Trust, Slimbridge: The Wildfowl Trust reports an excellent 1981 breeding season. Slimbridge reared 25 and the two other centres, Martin Mere and Peakirk, have also done well but no figures are available as yet. Overall this indicates that over 50 Brown Teal have been reared in the United Kingdom since DU sent two females in 1979. The Trust now plans to distribute pairs to their other two centres, to leading aviculturists in the United Kingdom, Europe and possibly the United States. The Wildfowl Trust and Ducks Unlimited feel that this is a very important safety aspect should anything unforeseen occur with the species in New Zealand.

1981/82 breeding season: Several breeders have reported eggs being laid during August and hopes are high that DU will break last season's record of 101 Brown Teal reared. This season we will have 40 pair of Brown Teal held by 18, possibly 20, members — well on the way to the 50 breeding pair target. The Wildlife Service will have 10 pairs for the coming season.

Pateke numbers improving

The brown teal (pāteke) is one of three endemic teal to New Zealand and the only one to fly. Both the Auckland Island and Campbell Island teal are flightless.

Mainly nocturnal and half the size of a mallard, this shy, omnivorous duck spends time on land foraging for invertebrates, seeds, fruit, grass, and foliage. With dark brown plumage, the males are particularly distinctive from their female counterparts during breeding time in late winter.

The slightly larger males in breeding plumage obtain a green iridescence on their heads, a dark chestnut breast plus occasionally a thin white neck ring too.

Like many of our native birds, this small-necked dabbling duck has dramatically suffered from mammalian predators, loss of habitat and hunting, resulting in a plummeting population to only 700 birds in the wild by the 1990s.

Brown teal were once widespread, but thanks to brown teal species co-ordinator Kevin Evans and the Department Of Conservation brown teal recovery group, in the past 15 years, this population decline has not only been halted, but reversed, building up to about 2500 birds in the wild today.

Numbers are slowly recovering and there are several contributors to this success:

Captive breeding facilities across New Zealand that produce birds for release.

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT), which provides facilities for flock mating for other institutions, and breeding plus pre-release conditioning and processing (banding, transmitter attachment, worming, disease screening, etc). Every captive raised bird goes to ICWT as its aviaries have stream-fed waterways for foraging, plus special feeders where the brown teal learn to obtain food. These feeders are also located at release sites.

DOC together with community groups undertake intensive predator control at release sites.

There are generally four releases of brown teal a year and the latest release of 32 birds was in August in the Abel Tasman National Park in an area managed by Janszoon.

Preparing the birds for release is an exhausting but rewarding task for all those involved at ICWT (assisted by Kevin Evans).

All release sites are vigorously assessed to ensure pāteke are released into areas with adequate protection and habitat to support self-sustaining populations.

[Ducks Unlimited was instrumental in early conservation efforts from 1975 with its ‘Operation Pateke’, New Zealand’s first large-scale co-ordinated brown teal breeding programme. – Editor]

Pateke doing well

Pateke Spotter: On the October 5 last year, Wayne Watson counted 32 Pateke at Whananaki, on Northland’s east coast - just north of Whangarei.

DU released Pateke at Whananaki in the 1980s and while they survived for long periods the massive predator expansion in Northland caught up with them, but now there is some serious predator control taking place on Northland’s east coast with very positive results.

Pateke success at Tawharanui

Pateke success at Tawharanui

Matt Maitland

Senior Ranger Open Sanctuaries

Northern Regional Parks

To save Pateke

To save Pateke Knowledge, care and endurance

Positive aspects of the recovery programme

1. Flock mating/natural pairing of Pateke was the key to the highly successful captive breeding programme – together with the enthusiasm of participants. Flock mating is now being used in a number of rare waterfowl recovery programmes.

2. Captive reared brown teal adapt readily to a wild environment, natural or created.

3. In Northland captive reared Pateke released at Mimiwhangata, Whananaki and Purerua between 1986-1992 survived for long periods and produced offspring – in spite of little predator control, with predator control Pateke are doing well.

4. Where predator control programmes have been in operation at suitably selected quality release sites in Northland (and more recently on the Coromandel) Pateke have survived very well and have successfully reared many progeny.

5. In the absence of waterfowl hunting and predators, captive reared brown teal released into quality Pateke habitat have few problems adapting to the wild.

6. A gradual transition from captive bred to wild, using pre-release pens and a supplementary diet was successful.

7. Brown teal are by far the most predator vulnerable species amongst all species of waterfowl

8. Captive reared teal released on off-shore islands that have suitable predator-free habitat survive and breed well.

9. When the release of captive reared Pateke into quality habitat is coupledwith predator control, a pre-release aviary, supplementary feeding and with the site having an adequate area for a significant population increase (such as at: Mimiwhangata, Purerua and Port Charles), the recovery process is a very simple one!

10. Between 1969-1992 it was learnt that releasing captive reared Pateke at a large number of unsuitable and disconnected habitats, with 35 different sites being used, achieved little, was counterproductive and very expensive.

11. Since the 2000 Audit of the recovery programme steady progress has been made towards increasing the wild populations of Pateke.

Starting in 2009 a150 captive reared Pateke have been released in Fiordland, but it is too early to predict the outcome of this programme.

Pateke were once widespread throughout Fiordland, the habitat is still excellent and with ongoing predator control a South Island population could be re-established.

The 2000 audit of the pateke recovery programme

Recovery mode

The recovery on the Coromandel clearly endorses the philosophy that provided Pateke have suitable habitat, protection from predators and ongoing management support they will survive and breed very successfully, with the success on the Coromandel possibly being the most rapid recovery of an endangered duck.

Negative aspects of Recovery programme

Between 1975 and 2002 there were 2000 Pateke released into mainland wetland sites, with all releases failing to slow the species decline, largely due to:

• Lack of continuity amongst Pateke management personnel and others directly involved in planning the survival of Pateke.

• Sites used were poorly selected.

• No pre-release study to see if there was an adequate food source.

• No pre-release study to determine whether the habitat was suitable.

• Little predator control and little knowledge of the subject.

• Little understanding about the main predators to control/ eliminate.

• Until early 2000 no sites had ongoing predator control.

• Many sites were out on a limb, with no wild Pateke in the area. • Many sites had no adjacent wetlands for progeny expansion or to which adults could escape.

• Many sites had no loafing facilities or aerial protection.

• Insufficient supplementary feeding of released birds. The value of this is recorded in a paper published in 2013.

• Pre-release aviaries rarely used.

• Competing waterfowl were present.

• Hybridisation with mallards and grey teal occurred.

• Instant dispersal of released birds occurred.

• A lack of ongoing support.

• A lack of monitoring of released birds.

Valiant efforts to save ducks from extinction

A brief History of Ducks Unlimited Operation Pateke.

Neil Hayes QSM, DUNZ Life Member

Time is overdue to document what I believe is the most significant contribution made by any conservation group in the world – that is Ducks Unlimited (NZ) efforts to save the endangered NZ Brown Teal (Anas chlorotis) from extinction.

The contribution by DUNZ starting in 1975 was inspirational. DUNZ was founded in 1974 by Jack Worth - with a few like-minded individuals: Ian Pirani, Paul Pirani, Neil Hayes and Trevor Voss - all wetland and waterfowl enthusiasts.

In 1974 Jack suggested the DU profile could be considerably enhanced by dedicated recovery programmes for brown teal and grey teal. “Operation Pateke” and “Operation Gretel” were launched with clear objectives. These project titles were unique to DU and it was the first organisation to use the word “Pateke” (Maori brown teal).

Operation objectives were:

1. To establish 50 breeding pairs of Brown Teal in captivity

2. To breed over 1000 Brown Teal in captivity and release them into suitable areas

3. To save Brown Teal from extinction

In 1976 I was appointed Director of the project and continued in this role until 1991. My introduction to Pateke was in 1970 during a visit to waterfowl enthusiast Trevor Voss – a dairy farmer near Stratford. Trevor was the pioneer of breeding Pateke in captivity and on the day of our visit he had 21 recently reared Pateke in a mobile aviary on his lawn.

Just on dusk Trevor asked me to help catch three Pateke in an aviary to move to another aviary. The aviary was knee deep in grass and after a half hour of trying to find them we gave up – but just on dusk they appeared! I thought what a strange bird and I’ve spent the last 40 years attempting to understand Pateke.

By 1973 I was breeding Pateke in captivity, starting with a wild pair caught on Great Barrier Island by NZ Wildlife Service. Within three months they hatched five offspring and reared all five.

Over the next 19 years we reared close to 200 Pateke in our Wainuiomata home garden – this featured numerous times on national TV, generating great publicity for DU and Pateke!

Pateke in the wild - 1973

My introduction to Pateke in the wild was during a trip to Russell, Bay of Islands, December 1973 to visit to wife Sylvia’s sister’s family.

My interest in saving brown teal prompted Sylvia’s sister to say “there are hundreds just down the road”. How right she was! At Parakura Bay south of Russell on the east coast we counted 96 brown teal and when Grant Dumbell was completing his PhD on Pateke between in 1986 - 1991 there was still a healthy population. By the mid 1990s there were none.

Brief natural history of Pateke

Fossil research by Trevor Worthy determined Pateke have been present in New Zealand for over 10,000 years and was once the most populous New Zealand waterfowl. Pateke were found throughout New Zealand’s once vast wetlands and inhabited lakes, rivers, lagoons, ponds, creeks, forest streams, swamps and estuaries. The 2002 fossil research confirmed what Peter Scott (Founder of the Wildfowl & Welands Trust) wrote in 1960. “Brown teal are an ancient and primitive form of duck”.

Large Pateke populations were also on Stewart Island, the last sighting in 1972 and on the Chatham Islands, last sighting in 1920. Pateke were believed to have become extinct in the South Island during the 1980s.

So, from millions of Pateke throughout the country until 1800 the decline to less than 850 by 1999 represents the world’s most dramatic decline of a waterfowl species!

Pateke are believed to have evolved from the very beginning of life in New Zealand, resulting in them having many unique dabbling duck behavioural characteristics, as well as unique colour, body shape, egg size, vocal sound and more.

Once New Zealand’s most common duck, estimated at several million, Pateke have been under threat of premature extinction (influenced by humans) since Europeans arrived in New Zealand in the 1840s; accompanied by rats, cats, dogs, ferrets, stoats, weasels and hedgehogs; all of which found the country’s endemic birds easier to kill and probably more palatable than imported rabbits, hares, possums, mallards, black swan, geese, etc! These alien predators also enjoy the eggs of our endemic birds and so wreaked havoc amongst the country’s endemic bird numbers. This was recognised as early as the mid 1850s.

European immigrants bought sporting firearms and duck hunting had a major impact on Pateke survival and in spite of Pateke being accorded legal protection in 1921 many continued to be shot during duck hunting season.

Wetland destruction was also rampant until the 1990s this, in association with predation and duck hunting, impacted heavily on Pateke survival. Prior to 1990 70 percent of New Zealand once vast wetlands and 50 percent of New Zealand indigenous forests had been eliminated.

Self introduced species such as harrier and pukeko also influenced the decline of Pateke, and all New Zealand endemic birds, frogs and invertebrates.

Captive breeding While captive breeding of Pateke was gradually increasing, with 19 birds reared in 1976, 18 in 1977, 29 in 1978 and 45 in 1979, numbers increased dramatically soon after DU was awarded a Mobil Oil Environmental Grant in 1979 - to hold a Brown Teal Management Seminar in Auckland in July 1980. Twenty five people attended, including from the NZ Wildlife Service, personnel from Auckland and Wellington Zoos, major aviculturalists and DU members keen to join the recovery programme. In addition to this important award, and immediately upon his appointment as Director of the NZ Wildlife Service Ralph Adams MBE phoned the DU Secretary in 1979 informing him that the entire brown teal recovery programme was to be handed to Ducks Unlimited. The proceedings of the seminar were published by DU in 1981, the outcome being that annual productivity jumped to 89 birds reared by DU participants in 1981. Another 47 were reared by the Mt Bruce National Wildlife Centre.

The published document entitled “The Aviculture, Re-Establishment & Status of the New Zealand Brown Teal” covered aviary design, the needs of Pateke in captivity, the Re-Establishment programme and the numbers of Pateke in the wild in 1981. After publication, Pateke reared in captivity expanded dramatically, as did the number of breeders and by 1984 DU had 39 captive breeders spread from Northland to Southland holding over 60 pairs and producing over 100 Pateke/season, with a record 153 reared in 1987. All this was greatly assisted by the injection of new blood from Great Barrier Island in 1974 by the Wildlife Service and a 1987 capture totally organised by DUNZ. For many years the Wildlife Service paid breeders $5 and DU also paid each breeder $5 for each Pateke reared.

DU’s success with Pateke was recognised as the world’s most successful captive breeding programme for an endangered waterfowl species and the same DU flock mating programme began to be used world-wide and is now a standard procedure. Such status and recognition was an incredible achievement for DUNZ.

Aviaries

One thing learnt early in the captive breeding was that each pair must be retained in their own ‘exclusive’ aviary – because a mated pair of Pateke is the most murderous of all waterfowl. In a captive situation paired Pateke will kill other waterfowl in the aviary, including other Pateke.

The Mobil Oil Seminar publication discussed the aviary requirements for holding a pair of Pateke in captivity and it was soon determined that a flock mated pair would breed in their first season, with the number from each broods averaging four.

A combination of a good size pond, clean water, lots of cover, a food tray that only needs filling once per week, at least two nesting boxes, loafing platforms, a dabbling area, a totally rat/mouse/predator free environment, were all found to be an excellent guide to success. So much so that one captive female Pateke lived to be 24 years and 3 months. Lots of others have lived to be 12 to 18 years. This indicates the simplicity of the recovery programme – provide Pateke with a quality, predator free environment and they survive for many years.

In the wild we know of one male Pateke was captured again 90 kilometres from where he was released 8 years earlier. With such large numbers being reared a facility was needed to hold large numbers of birds prior to release and Jim Campbell built a large holding aviary at his farm north of Masterton.

Pateke reared in the South Island were air freighted to Wellington, picked up by DU and delivered to Jim’s aviary – well able to hold 100s of Pateke over fairly long periods. Most reared there went to release sites in the North Island.

The added value of the holding aviary was many birds were bonded as pairs before they were released.

Pateke worth saving Having evolved from the beginning of life in New Zealand and with unique features not found in any other species of waterfowl makes Pateke worth saving. Some unique behaviours are:- Nocturnal behaviour. It is believed this trait was generated by Haast’s Eagle (Harpagornis moorei) and the trait, once termed as crepuscular, expanded as the harrier population grew into millions

- Unlike other endemic waterfowl Pateke were once widespread throughout every type of New Zealand wetland.

- Selective in pairing behaviour and a monogamous relationship.

- The murderous nature of adult pairs in captivity, where it is impossible to hold more that one pair of teal in an aviary, and towards their fledged progeny; but birds of the year will live quite happily together until pairing commences – after which a pair must be removed very quickly to their own aviary.

- The murderous nature of pairs in the wild – towards other pairs and their progeny, particularly the male, towards his fledged offspring.

- Long-term parental attention provided to their progeny by both parents, at least until the progeny are fully fledged.

- An incredibly long lifespan in captivity.

- Great climbing ability.

- Incredible vulnerability to predation.

- Incredible vulnerability to being shot during duck season – in spite of total protection since 1921.

- Preference for estuarine habitat since Pateke began its retreat from predators.

- Colour, body shape, size, weight, courtship, displays, and vocal sounds.

- Pre and post-copulatory behaviour - invariably there isn’t any!

- Feeding patterns.

- What they eat.

- Small clutch size – 5-6 eggs.

- Egg shape, size and weight – huge eggs for size of female.

- Colour, size and weight of progeny.

- Specialised bill, with very prominent lamellae.

- Flocking behaviour – teal become very gregarious after breeding season and head to favourite flock site.

- Unique habitat requirements.

- Preference for walking instead of flying.

- Failure to adapt to environmental changes.

The releases at Puke Puke and Nga Manu were organised by DUNZ members and whilst a number of birds released at Puke Puke reared young, very few of the birds survived for long periods, simply because the reasons for Pateke heading for extinction had not been addressed; the main reason being PREDATORS, accompanied by duck shooting.

Other releases in the Manawatu were undertaken by the NZ Wildlife Service, as was a single release at the Kaihoka Lakes, Nelson in 1978.

In addition and knowing that Pateke have done well on off-shore islands three DU organised three releases of Pateke on Matakana Island, Tauranga, between 1980 - 1981. Sadly, all the releases between 1969 and 1983, including those on Matakana Island failed to re-establish and in 1984 it was decided to concentrate the release programme in Northland, along the east coast that was still quality Pateke habitat – and where approximately 1200 Pateke were still surviving.

Release programme in Northland

By 1984 large numbers were reared each season and the Northland release programme commenced in August 1984. From 1984 to 1991 all Northland releases were organised by DUNZ, with considerable support from Dr Murray Williams of the NZ Wildlife Service.

Jim Campbell, Allan Elliott and I spend seven years carrying Pateke from Masterton to Northland, mainly in Jim’s Chevy Ute.

The August releases took place at the 350-hectare Government owned Mimiwhangata Farm Park on the east coast just north of Whangarei, where considerable Pateke habitat had been created and the farm was just south of the famous Helena Bay Pateke roost site: it regularly supported 50-70 Pateke and was only a stone throw from the large holiday camping grounds.

Two large lagoons were created by the Wildlife Service, together with lots of small breeding ponds and there was a small estuary on the farm. On the same day another Northland release took place at the upper reaches of the Matapouri Estuary – a little south of Mimiwhangata and only 20 minutes drive from Whangarei.

Recalling that in England pre-release aviaries are always used for holding captive reared birds for several weeks before the aviary door is opened. So for the first Northland release of captive reared DU Pateke the Wildlife Service erected large aviary at both Mimiwhangata and Matapouri - to hold the birds while they became adjusted to their new surroundings. At the Nga Manu Sanctuary a pre-release aviary was also used.

The aviaries worked well at Nga Manu and Mimiwhangata, but at Matapouri several Pateke escaped before a hole was plugged!

In total 42 Pateke were released at Mimiwhangata and 54 at Matapouri on August 4, 1984 and because Pateke were uplifted from various breeders on the way to Northland they had to be banded prior to being place in the pre-release. These two sites were the only Northland site where pre-release aviaries were used.

Between 1984 and 1991 a total of just under 600 captive reared brown teal were released by DU onto five different wetlands in Northland - Mimiwhangata, Matapouri, Takou Bay, Purerua and Urupukapuka Island - with all releases carried out by DU personnel. One of the most remarkable things about all DU releases of Pateke between 1975-1991 is that only one bird of over 1000 released by DU had died in transit.

Two of the preferred Northland sites were Mimiwhangata and Purerua – with 295 Pateke being released at Mimiwhangata and 320 at the Purerua. The DU Pateke Recovery Team believed the 7-hectare created lake on the Purerua Peninsula, just north of Kerikeri was an excellent site and Pateke were known to breed there and in adjacent wetland.

Sadly the Dept of Conservation controlled Pateke Recovery group ignored the Purerua site for over 10-years.

Survival in Northland

Survival at Mimiwhangata, Purerua and Matapouri was extremely good – in spite of predator control only taking place at Mimiwhangata: and for only a short time.

A photo taken in early December 1987 showed 45 Pateke clearly identified from a release of 64 three and a half months earlier. Over 60 Pateke were present and it is believed all 64 were still alive.

The survival rate at Mimiwhangata was largely due to Pateke being fed a supplementary diet every morning and an extensive predator control programme.

The survival at the Purerua site was also good, but they needed the supplementary food and predator control. There were numerous reports of Pateke being seen at many sites in the district.

Matapouri survival was also encouraging and 18-months after the first release I counted 22 Pateke in the estuary.

Modern era (1991-2014) recovery programme

Unfortunately when DOC took over the recovery programme in 1991 they categorically stated that no more than 40 Pateke would be required each season. The result was numerous Pateke breeders threw in the towel and DU had a period of loss of interest.

By 1993 Pateke numbers in the wild were plummeting. I discussed this in an article published in NZ Outdoor magazine, entitled “The rapidly approaching demise of the New Zealand Brown Teal.” The Department took note and held an informal recovery group meeting at the Mimiwhangata Farm Park. The meeting decided to concentrate Pateke recovery in Northland with expanded predator control and over the next two years Northland Pateke numbers increased steadily. With Pateke also present on a number of small offshore islands; including Kapiti, Urupukapuka, Tiritiri Matangi and Little Barrier the total number in the wild in 1987 was 3000. But, by 2000 Pateke in Northland had declined to 350, on Great Barrier Island to 500 and on the Coromandel Peninsula to less than 20 birds. Two years after the involvement DOC again lost interest in Northland and commenced a release programme into totally unsuitable areas; such as Travis Wetland in Christchurch, Tawharunui (Warkworth), Cape Kidnappers (Hawke’s Bay), Warrenheip (Waikato) and more recently Fiordland. Though these sites had predator control programmes they all failed because:

1. There are no wild populations of Pateke in the area.

2. Habitat was not suitable.

3. No suitable flock-sites.

4. No suitable Pateke habitat adjacent to these sites.

5. No suitably protected adjacent wetland for population expansion.

The result - by 1999 nation-wide Pateke numbers had again dramatically plummeted – from close to 3000 in 1987 (Including Pateke on offshore island) to less than 800 in 1999 - and our graph showed that Pateke would be extinct on the mainland by 2004 and totally extinct by 2015.

Bearing in mind the 3000 recorded in 1987 was likely a conservation figure the dramatic race towards extinction is the most disastrous ever recorded for a rare and endangered waterfowl species.

The Race Towards Extinction – 1988 to 1998

3000 *

1700 *

1200 *

1000 *

900 *

800 *

1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998

In September 1999 two Pateke pragmatists featured on TV ONE News and in no uncertain terms pointed out that brown teal were in grave danger of premature extinction, and severely criticising the Department’s performance in the Pateke recovery programme.

The TV ONE presenter was undoubtedly the ‘star’ of the news item – standing in front of a Pateke aviary, she said “The whole recovery programme is a simple one, you give brown teal a protected environment like this and they live to be 24 years and 3 months.”

The outcome from this news item was that the Department carried out an audit of the programme, interviewing 39 people who were known to have had some involvement with brown teal and in 2000 the findings, recommendations and objectives of how to save Pateke from extinction were published. A two-day seminar/workshop was held in Kerikeri to determine how best the Audit recommendations could be implemented.

The workshop recommended the implementation of major predator control programmes and the race of Pateke towards extinction has being retarded. The Pateke population is steadily increasing, but only in the three areas of the country now recognised as vital to long-term Pateke survival; Northland, Great Barrier Island and Coromandel Peninsula; all three areas were where Pateke began their escape from the massive nation-wide increase in predators - feral cats, ferrets, stoats, weasels, rats, hedgehogs, harriers, pukeko, etc, believed to have been during the late early 1900s.

The rapid decline in Northland and the Coromandel can be attributed to the spread of predators, but on Great Barrier Island where there are no mustelids, hedgehogs or duck hunting, but large populations of feral cats, two species of rat, feral dogs (lost by pig hunters), Pukeko and the harrier hawk, the race towards extinction can be clearly attributed to an explosion of predators in all three areas; along with an almost total lack of endangered species management. Domestic dogs are also known to eliminate Pateke in these critically important areas.

Success on the Coromandel Peninsula

Little is known about the retreat of Pateke to Northland, the Coromandel and Great Barrier Island; though Great Barrier Island once had the largest national population of Pateke. However, in the early 1900s there was no record of Pateke being present on Great Barrier Island, and in 1868 Hutton, a highly regarded ornithologist, failed to record them in his extensive Great Barrier Island bird survey, but by 1987 there was 1500 Pateke on Great Barrier Island and 1200 on the east coast of Northland, but less than 20 on the Coromandel. Pateke were widespread on the Coromandel in the early 1900s but with the spread of predators less than 20 were surviving in the Port Charles area near the top of the Coromandel.

Thanks to the 2000 Audit the release of captive reared Pateke commenced on the Coromandel in 2003 and ended in 2007 with 250 Pateke released. This release was supported by the existing and extensive predator control programme in the Moehau Ranges in operation since 1999 and by 2013 there are several hundred Kiwi surviving in the ranges. An extensive predator control programme for Pateke at Port Charles and environs was launched in 2001, with a high level of survival of both released and wild teal.

And from 20 to 750 Pateke on the Coromendel is an incredible success story and clearly confirmed precisely what the TV Presenter stated in 1999 – “Provide brown teal with a predator free environment and they will live for 24-years”! The level of survival of released birds, their adaptability and their breeding success, coupled with major predator control programmes, no duck hunting and outstanding support from the local Port Charles community, including farmers, is an outstanding example of what can be achieved in a short space of time. Brown teal are now being observed in an increasing number in many areas of the Peninsula with one flock of 180 being counted in 2012 at Waikawau Bay.

istorically, a peninsula has proven to be readily defensible against predators and with ongoing predator control on the Coromandel Peninsula a population of over 2000 Pateke could be achieved.

Besides well organised and intensive predator control on the Coromandel the support of the local farming community and residents has been an intrinsically important part of the success, with a number of land owners creating quality Pateke habitat and the locals carrying out much of the predator control work.

In addition financial contributions from The Moehau Environmental Group, Banrock Station Wines of Adelaide, Isaac Wildlife Trust, DUNZ, DOC, Brown Teal Conservation Trust and, critically important to the whole programme - the Pateke captive breeders - all helped ensure the success of the Coromandel re-establishment programme.

There is still much to be done before Pateke are anywhere near being saved from extinction and a future for the species is assured. DUNZ can be justly proud of its achievements with Pateke.

Next issue of Flight - The Positives and negatives of Pateke recovery programme.

Northland Pateke recovery

Captive Breeding

Recovery Group Future

Pateke flourish, Cape Sanctuary

Outside the sanctuary, John Winters and I visited around 22 dams not far from the Cape Sanctuary boundary. Pateke were counted on the large Haupouri shooting dam – 12 of them and Andy Lowe saw 18 on both Clifton and Taurapa stations. Three pateke were also spotted on a dam at Elephant Hill by some avid birders who reported them to Sue McLennan while she was taking them on a Kiwi Walk. I was surprised that there were no pateke on the Nilsson’s dams and even Blackie on Te Awanga lagoon didn’t show (he is around seven years old now so maybe has done his dash). Overall though, a good count. It is a snapshot of what’s out there and at the very least around 10 percent of the national population. The exciting developments with the Cape to City project (see http://capetocity.co.nz/about/ and https://www.facebook. com/capetocity) will help provide safer habitat for pateke taking up residence outside Cape Sanctuary.

How many golf courses can boast that they have a critically endangered duck nesting only 10 metres from the Club House entrance? Can you spot the pateke nest behind the log in the centre of the picture? Cape Kidnappers landscaping team recently disturbed a nesting pateke sitting on six eggs, in the golf course drop off/turning area. The area was being replanted. The female had returned by the following morning and appeared oblivious to vehicles coming and going. The eggs all hatched and mum has moved the family off to somewhere a little quieter.

Tamsin Ward Smith

Habitat te Henga

Mutterings from the Marsh

Although rarely seen, their radio transmitters give the show away and let us know they have tended to take up residence in separate parts of the wetland. Many are clustered within a few hundred metres of the release site, while others have shunned their companions and are contentedly at the extremes of the wetland, west or east.

Required by the Pateke Recovery group to monitor the birds intensively for the fist six months, but only at monthly intervals beyond, we have been able to have volunteers maintain a weekly survey. With spring upon us and with certain pairs sticking close to each other we hope the more frequent monitoring will give us an indication if nesting is occurring.

Another more sombre reason though is that if a mortality signal is generated, we might be aware sooner and be able to recover a body to possibly determine cause of death. Three times we have had the mortality tone, and two carcasses were found while in the third case the transmitter was accurately tracked to almost 2-metre deep water. Was this a death or a case of harness failure? With that possibility and with an analysis of one carcass that showed no signs of predation but rather a tarsus fracture indicating a probable duck vs. vehicle incident, we have been fairly pleased with our predator control measures.

Maintaining predator control has been a large group of volunteers who check traps- some on their own properties, others checking traps on private or public land. Almost half of the traps though, are tended by our contractor who walks two 12 -14 km trap lines on a regular two weekly schedule. This large number of traps has allowed us to conduct an experiment which is ongoing.Alternate traps are baited with salted rabbit meat or a commercial dried rabbit product. The Statistics Department of Auckland University is analysing the results and by next year will be able to tell us if one is more efficient a lure than the other.

A contentious topic recently, but one I’ve been promoting is the use of UAV not for the casual model aircraft enthusiast, but as a genuine conservation tool. Chancing upon a local UAV manufacturer I was able to get him to look into using a UAV [drone] as an aerial radio receiver.

Other activities include a recent extensive survey of fernbird at three sites comparing the Forest & Bird reserve where predator control has been maintained for 15 years to two new sites only trapped over the past 18 months. This will give baseline date to use when we are able to add rodent control to some of the new sites. Spotless crake were to come in for a similar survey using sound playback in early October.

Meanwhile bittern are being seen more and more frequently. Nice to think it is due to our pest management, but it’s as likely to be due to more observations by interested persons. As with most conservation though, the hardest task is fundraising and a second translocation next year is dependant on successful applications. I’ll tell you how that went in a future update.

John Summich.