Displaying items by tag: Endangered Species

Another lost duck?

Alan Fielding follows up his story on the white-eye duck with that of another duck disappearance – the pink-eared duck.

The pink-eared duck or zebra duck (Malacorhynchus membranaceus), whose Maori name appears to be lost with it, is one of only two genera of the tribe Malacorhynchini, the other being the Salvadori’s duck from New Guinea.

The pink-ear, known in New Zealand from bone fragments of two individuals found by Dr Robert Falla in 1939-41 at Pyramid Valley, north Canterbury, is of geologically recent origin (about 3,500 years), strongly suggesting they are of the Australian species which is widely distributed in inland south-east and south-west Australian and also to a lesser extent in the north-east.

Taxonomical discussions have suggested that the bone fragments may be of a separate species – the so-called Scarlett’s duck – but there remains the doubt.

Pink-ears are a highly nomadic species and their numbers vary greatly depending on the rainfall. Their outstanding mobility makes it easy to see how after a good westerly storm, this country might have been attractive to them. Although the lack of much evidence suggests these birds were vagrants and did not breed here, a stray pink-ear turned up in Auckland in 1990, proving just how mobile the species is.

One thing remains certain: they were self-introduced and therefore indigenous. Their numbers in New Zealand may have escaped suitable preservative sedimentation and they were perhaps more numerous. If this had been during the pre-Maori period,it could explain the loss or non-existence of a name.

Pink-ears are astonishingly quiet, trusting birds which leads one to wonder whether that led to their downfall in colonising New Zealand. These ducks are unmistakable and quite delightful with their distinct zebra stripes and large bill – a bill that is spatulated to a much greater degree than the shovelers and gives them a distinct square-tipped appearance.

Unlike shovelers, the young pink-ears are hatched with the spatulate bill already present along with the distinct “pink ear”, a small pinkish patch slightly behind the eye and difficult to see at a distance. This, as with the zebra stripes, is pale in the juveniles.

The strangely large bill, with its nostrils higher up than usual, is an efficient strainer of tiny organisms such as algae, plankton, insects, crustaceans, and molluscs from the water and mud. This foraging takes place usually without up-ending and never by diving.

Breeding is usually heralded by the sudden invasion of typically shallow, seasonal wetlands (rainfall not exceeding 40mm a year), preferably of long-established origin so that food species populations are high.

The water levels may recede quite rapidly so reproduction needs to be speedy and opportunistic so the nests, typically drowned in down, may be built almost anywhere, often in great density – and might be dispensed with altogether and replaced with “dump laying” even on top of active nests.

If conditions remain suitable, however, they may breed for almost the whole year, with both parents sharing nursery duties. It is thought they may pair for life. Both genders make a chirping, twittering, strange whistling sound, which while soft and deeper in the females and “purring” when communicating with young, can be quite noisy en masse. In flight, these birds utter an unusual trilling sound. Incorrectly believed to be weak fliers, they are quite strong and outstandingly manoeuvrable, extremely gregarious and freely sociable with other waterfowl, notable grey teal.

A highly specialised and successful species, it can inhabit seasonal inland shallow waters, brackish, marine or fresh, through to permanent deeper water and even coastal inlets and mangrove wetlands.

Considering the huge numbers of plant and animal species that have been lost to this country, why not recover what we can, even if it is not endemic?

established several public and private protected areas. He also instigated and coordinated the first National Mangrove Symposium (in Northland) for the Nature Conservation Council.

Valiant efforts to save ducks from extinction

A brief History of Ducks Unlimited Operation Pateke.

Neil Hayes QSM, DUNZ Life Member

Time is overdue to document what I believe is the most significant contribution made by any conservation group in the world – that is Ducks Unlimited (NZ) efforts to save the endangered NZ Brown Teal (Anas chlorotis) from extinction.

The contribution by DUNZ starting in 1975 was inspirational. DUNZ was founded in 1974 by Jack Worth - with a few like-minded individuals: Ian Pirani, Paul Pirani, Neil Hayes and Trevor Voss - all wetland and waterfowl enthusiasts.

In 1974 Jack suggested the DU profile could be considerably enhanced by dedicated recovery programmes for brown teal and grey teal. “Operation Pateke” and “Operation Gretel” were launched with clear objectives. These project titles were unique to DU and it was the first organisation to use the word “Pateke” (Maori brown teal).

Operation objectives were:

1. To establish 50 breeding pairs of Brown Teal in captivity

2. To breed over 1000 Brown Teal in captivity and release them into suitable areas

3. To save Brown Teal from extinction

In 1976 I was appointed Director of the project and continued in this role until 1991. My introduction to Pateke was in 1970 during a visit to waterfowl enthusiast Trevor Voss – a dairy farmer near Stratford. Trevor was the pioneer of breeding Pateke in captivity and on the day of our visit he had 21 recently reared Pateke in a mobile aviary on his lawn.

Just on dusk Trevor asked me to help catch three Pateke in an aviary to move to another aviary. The aviary was knee deep in grass and after a half hour of trying to find them we gave up – but just on dusk they appeared! I thought what a strange bird and I’ve spent the last 40 years attempting to understand Pateke.

By 1973 I was breeding Pateke in captivity, starting with a wild pair caught on Great Barrier Island by NZ Wildlife Service. Within three months they hatched five offspring and reared all five.

Over the next 19 years we reared close to 200 Pateke in our Wainuiomata home garden – this featured numerous times on national TV, generating great publicity for DU and Pateke!

Pateke in the wild - 1973

My introduction to Pateke in the wild was during a trip to Russell, Bay of Islands, December 1973 to visit to wife Sylvia’s sister’s family.

My interest in saving brown teal prompted Sylvia’s sister to say “there are hundreds just down the road”. How right she was! At Parakura Bay south of Russell on the east coast we counted 96 brown teal and when Grant Dumbell was completing his PhD on Pateke between in 1986 - 1991 there was still a healthy population. By the mid 1990s there were none.

Brief natural history of Pateke

Fossil research by Trevor Worthy determined Pateke have been present in New Zealand for over 10,000 years and was once the most populous New Zealand waterfowl. Pateke were found throughout New Zealand’s once vast wetlands and inhabited lakes, rivers, lagoons, ponds, creeks, forest streams, swamps and estuaries. The 2002 fossil research confirmed what Peter Scott (Founder of the Wildfowl & Welands Trust) wrote in 1960. “Brown teal are an ancient and primitive form of duck”.

Large Pateke populations were also on Stewart Island, the last sighting in 1972 and on the Chatham Islands, last sighting in 1920. Pateke were believed to have become extinct in the South Island during the 1980s.

So, from millions of Pateke throughout the country until 1800 the decline to less than 850 by 1999 represents the world’s most dramatic decline of a waterfowl species!

Pateke are believed to have evolved from the very beginning of life in New Zealand, resulting in them having many unique dabbling duck behavioural characteristics, as well as unique colour, body shape, egg size, vocal sound and more.

Once New Zealand’s most common duck, estimated at several million, Pateke have been under threat of premature extinction (influenced by humans) since Europeans arrived in New Zealand in the 1840s; accompanied by rats, cats, dogs, ferrets, stoats, weasels and hedgehogs; all of which found the country’s endemic birds easier to kill and probably more palatable than imported rabbits, hares, possums, mallards, black swan, geese, etc! These alien predators also enjoy the eggs of our endemic birds and so wreaked havoc amongst the country’s endemic bird numbers. This was recognised as early as the mid 1850s.

European immigrants bought sporting firearms and duck hunting had a major impact on Pateke survival and in spite of Pateke being accorded legal protection in 1921 many continued to be shot during duck hunting season.

Wetland destruction was also rampant until the 1990s this, in association with predation and duck hunting, impacted heavily on Pateke survival. Prior to 1990 70 percent of New Zealand once vast wetlands and 50 percent of New Zealand indigenous forests had been eliminated.

Self introduced species such as harrier and pukeko also influenced the decline of Pateke, and all New Zealand endemic birds, frogs and invertebrates.

Captive breeding While captive breeding of Pateke was gradually increasing, with 19 birds reared in 1976, 18 in 1977, 29 in 1978 and 45 in 1979, numbers increased dramatically soon after DU was awarded a Mobil Oil Environmental Grant in 1979 - to hold a Brown Teal Management Seminar in Auckland in July 1980. Twenty five people attended, including from the NZ Wildlife Service, personnel from Auckland and Wellington Zoos, major aviculturalists and DU members keen to join the recovery programme. In addition to this important award, and immediately upon his appointment as Director of the NZ Wildlife Service Ralph Adams MBE phoned the DU Secretary in 1979 informing him that the entire brown teal recovery programme was to be handed to Ducks Unlimited. The proceedings of the seminar were published by DU in 1981, the outcome being that annual productivity jumped to 89 birds reared by DU participants in 1981. Another 47 were reared by the Mt Bruce National Wildlife Centre.

The published document entitled “The Aviculture, Re-Establishment & Status of the New Zealand Brown Teal” covered aviary design, the needs of Pateke in captivity, the Re-Establishment programme and the numbers of Pateke in the wild in 1981. After publication, Pateke reared in captivity expanded dramatically, as did the number of breeders and by 1984 DU had 39 captive breeders spread from Northland to Southland holding over 60 pairs and producing over 100 Pateke/season, with a record 153 reared in 1987. All this was greatly assisted by the injection of new blood from Great Barrier Island in 1974 by the Wildlife Service and a 1987 capture totally organised by DUNZ. For many years the Wildlife Service paid breeders $5 and DU also paid each breeder $5 for each Pateke reared.

DU’s success with Pateke was recognised as the world’s most successful captive breeding programme for an endangered waterfowl species and the same DU flock mating programme began to be used world-wide and is now a standard procedure. Such status and recognition was an incredible achievement for DUNZ.

Aviaries

One thing learnt early in the captive breeding was that each pair must be retained in their own ‘exclusive’ aviary – because a mated pair of Pateke is the most murderous of all waterfowl. In a captive situation paired Pateke will kill other waterfowl in the aviary, including other Pateke.

The Mobil Oil Seminar publication discussed the aviary requirements for holding a pair of Pateke in captivity and it was soon determined that a flock mated pair would breed in their first season, with the number from each broods averaging four.

A combination of a good size pond, clean water, lots of cover, a food tray that only needs filling once per week, at least two nesting boxes, loafing platforms, a dabbling area, a totally rat/mouse/predator free environment, were all found to be an excellent guide to success. So much so that one captive female Pateke lived to be 24 years and 3 months. Lots of others have lived to be 12 to 18 years. This indicates the simplicity of the recovery programme – provide Pateke with a quality, predator free environment and they survive for many years.

In the wild we know of one male Pateke was captured again 90 kilometres from where he was released 8 years earlier. With such large numbers being reared a facility was needed to hold large numbers of birds prior to release and Jim Campbell built a large holding aviary at his farm north of Masterton.

Pateke reared in the South Island were air freighted to Wellington, picked up by DU and delivered to Jim’s aviary – well able to hold 100s of Pateke over fairly long periods. Most reared there went to release sites in the North Island.

The added value of the holding aviary was many birds were bonded as pairs before they were released.

Pateke worth saving Having evolved from the beginning of life in New Zealand and with unique features not found in any other species of waterfowl makes Pateke worth saving. Some unique behaviours are:- Nocturnal behaviour. It is believed this trait was generated by Haast’s Eagle (Harpagornis moorei) and the trait, once termed as crepuscular, expanded as the harrier population grew into millions

- Unlike other endemic waterfowl Pateke were once widespread throughout every type of New Zealand wetland.

- Selective in pairing behaviour and a monogamous relationship.

- The murderous nature of adult pairs in captivity, where it is impossible to hold more that one pair of teal in an aviary, and towards their fledged progeny; but birds of the year will live quite happily together until pairing commences – after which a pair must be removed very quickly to their own aviary.

- The murderous nature of pairs in the wild – towards other pairs and their progeny, particularly the male, towards his fledged offspring.

- Long-term parental attention provided to their progeny by both parents, at least until the progeny are fully fledged.

- An incredibly long lifespan in captivity.

- Great climbing ability.

- Incredible vulnerability to predation.

- Incredible vulnerability to being shot during duck season – in spite of total protection since 1921.

- Preference for estuarine habitat since Pateke began its retreat from predators.

- Colour, body shape, size, weight, courtship, displays, and vocal sounds.

- Pre and post-copulatory behaviour - invariably there isn’t any!

- Feeding patterns.

- What they eat.

- Small clutch size – 5-6 eggs.

- Egg shape, size and weight – huge eggs for size of female.

- Colour, size and weight of progeny.

- Specialised bill, with very prominent lamellae.

- Flocking behaviour – teal become very gregarious after breeding season and head to favourite flock site.

- Unique habitat requirements.

- Preference for walking instead of flying.

- Failure to adapt to environmental changes.

The releases at Puke Puke and Nga Manu were organised by DUNZ members and whilst a number of birds released at Puke Puke reared young, very few of the birds survived for long periods, simply because the reasons for Pateke heading for extinction had not been addressed; the main reason being PREDATORS, accompanied by duck shooting.

Other releases in the Manawatu were undertaken by the NZ Wildlife Service, as was a single release at the Kaihoka Lakes, Nelson in 1978.

In addition and knowing that Pateke have done well on off-shore islands three DU organised three releases of Pateke on Matakana Island, Tauranga, between 1980 - 1981. Sadly, all the releases between 1969 and 1983, including those on Matakana Island failed to re-establish and in 1984 it was decided to concentrate the release programme in Northland, along the east coast that was still quality Pateke habitat – and where approximately 1200 Pateke were still surviving.

Release programme in Northland

By 1984 large numbers were reared each season and the Northland release programme commenced in August 1984. From 1984 to 1991 all Northland releases were organised by DUNZ, with considerable support from Dr Murray Williams of the NZ Wildlife Service.

Jim Campbell, Allan Elliott and I spend seven years carrying Pateke from Masterton to Northland, mainly in Jim’s Chevy Ute.

The August releases took place at the 350-hectare Government owned Mimiwhangata Farm Park on the east coast just north of Whangarei, where considerable Pateke habitat had been created and the farm was just south of the famous Helena Bay Pateke roost site: it regularly supported 50-70 Pateke and was only a stone throw from the large holiday camping grounds.

Two large lagoons were created by the Wildlife Service, together with lots of small breeding ponds and there was a small estuary on the farm. On the same day another Northland release took place at the upper reaches of the Matapouri Estuary – a little south of Mimiwhangata and only 20 minutes drive from Whangarei.

Recalling that in England pre-release aviaries are always used for holding captive reared birds for several weeks before the aviary door is opened. So for the first Northland release of captive reared DU Pateke the Wildlife Service erected large aviary at both Mimiwhangata and Matapouri - to hold the birds while they became adjusted to their new surroundings. At the Nga Manu Sanctuary a pre-release aviary was also used.

The aviaries worked well at Nga Manu and Mimiwhangata, but at Matapouri several Pateke escaped before a hole was plugged!

In total 42 Pateke were released at Mimiwhangata and 54 at Matapouri on August 4, 1984 and because Pateke were uplifted from various breeders on the way to Northland they had to be banded prior to being place in the pre-release. These two sites were the only Northland site where pre-release aviaries were used.

Between 1984 and 1991 a total of just under 600 captive reared brown teal were released by DU onto five different wetlands in Northland - Mimiwhangata, Matapouri, Takou Bay, Purerua and Urupukapuka Island - with all releases carried out by DU personnel. One of the most remarkable things about all DU releases of Pateke between 1975-1991 is that only one bird of over 1000 released by DU had died in transit.

Two of the preferred Northland sites were Mimiwhangata and Purerua – with 295 Pateke being released at Mimiwhangata and 320 at the Purerua. The DU Pateke Recovery Team believed the 7-hectare created lake on the Purerua Peninsula, just north of Kerikeri was an excellent site and Pateke were known to breed there and in adjacent wetland.

Sadly the Dept of Conservation controlled Pateke Recovery group ignored the Purerua site for over 10-years.

Survival in Northland

Survival at Mimiwhangata, Purerua and Matapouri was extremely good – in spite of predator control only taking place at Mimiwhangata: and for only a short time.

A photo taken in early December 1987 showed 45 Pateke clearly identified from a release of 64 three and a half months earlier. Over 60 Pateke were present and it is believed all 64 were still alive.

The survival rate at Mimiwhangata was largely due to Pateke being fed a supplementary diet every morning and an extensive predator control programme.

The survival at the Purerua site was also good, but they needed the supplementary food and predator control. There were numerous reports of Pateke being seen at many sites in the district.

Matapouri survival was also encouraging and 18-months after the first release I counted 22 Pateke in the estuary.

Modern era (1991-2014) recovery programme

Unfortunately when DOC took over the recovery programme in 1991 they categorically stated that no more than 40 Pateke would be required each season. The result was numerous Pateke breeders threw in the towel and DU had a period of loss of interest.

By 1993 Pateke numbers in the wild were plummeting. I discussed this in an article published in NZ Outdoor magazine, entitled “The rapidly approaching demise of the New Zealand Brown Teal.” The Department took note and held an informal recovery group meeting at the Mimiwhangata Farm Park. The meeting decided to concentrate Pateke recovery in Northland with expanded predator control and over the next two years Northland Pateke numbers increased steadily. With Pateke also present on a number of small offshore islands; including Kapiti, Urupukapuka, Tiritiri Matangi and Little Barrier the total number in the wild in 1987 was 3000. But, by 2000 Pateke in Northland had declined to 350, on Great Barrier Island to 500 and on the Coromandel Peninsula to less than 20 birds. Two years after the involvement DOC again lost interest in Northland and commenced a release programme into totally unsuitable areas; such as Travis Wetland in Christchurch, Tawharunui (Warkworth), Cape Kidnappers (Hawke’s Bay), Warrenheip (Waikato) and more recently Fiordland. Though these sites had predator control programmes they all failed because:

1. There are no wild populations of Pateke in the area.

2. Habitat was not suitable.

3. No suitable flock-sites.

4. No suitable Pateke habitat adjacent to these sites.

5. No suitably protected adjacent wetland for population expansion.

The result - by 1999 nation-wide Pateke numbers had again dramatically plummeted – from close to 3000 in 1987 (Including Pateke on offshore island) to less than 800 in 1999 - and our graph showed that Pateke would be extinct on the mainland by 2004 and totally extinct by 2015.

Bearing in mind the 3000 recorded in 1987 was likely a conservation figure the dramatic race towards extinction is the most disastrous ever recorded for a rare and endangered waterfowl species.

The Race Towards Extinction – 1988 to 1998

3000 *

1700 *

1200 *

1000 *

900 *

800 *

1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998

In September 1999 two Pateke pragmatists featured on TV ONE News and in no uncertain terms pointed out that brown teal were in grave danger of premature extinction, and severely criticising the Department’s performance in the Pateke recovery programme.

The TV ONE presenter was undoubtedly the ‘star’ of the news item – standing in front of a Pateke aviary, she said “The whole recovery programme is a simple one, you give brown teal a protected environment like this and they live to be 24 years and 3 months.”

The outcome from this news item was that the Department carried out an audit of the programme, interviewing 39 people who were known to have had some involvement with brown teal and in 2000 the findings, recommendations and objectives of how to save Pateke from extinction were published. A two-day seminar/workshop was held in Kerikeri to determine how best the Audit recommendations could be implemented.

The workshop recommended the implementation of major predator control programmes and the race of Pateke towards extinction has being retarded. The Pateke population is steadily increasing, but only in the three areas of the country now recognised as vital to long-term Pateke survival; Northland, Great Barrier Island and Coromandel Peninsula; all three areas were where Pateke began their escape from the massive nation-wide increase in predators - feral cats, ferrets, stoats, weasels, rats, hedgehogs, harriers, pukeko, etc, believed to have been during the late early 1900s.

The rapid decline in Northland and the Coromandel can be attributed to the spread of predators, but on Great Barrier Island where there are no mustelids, hedgehogs or duck hunting, but large populations of feral cats, two species of rat, feral dogs (lost by pig hunters), Pukeko and the harrier hawk, the race towards extinction can be clearly attributed to an explosion of predators in all three areas; along with an almost total lack of endangered species management. Domestic dogs are also known to eliminate Pateke in these critically important areas.

Success on the Coromandel Peninsula

Little is known about the retreat of Pateke to Northland, the Coromandel and Great Barrier Island; though Great Barrier Island once had the largest national population of Pateke. However, in the early 1900s there was no record of Pateke being present on Great Barrier Island, and in 1868 Hutton, a highly regarded ornithologist, failed to record them in his extensive Great Barrier Island bird survey, but by 1987 there was 1500 Pateke on Great Barrier Island and 1200 on the east coast of Northland, but less than 20 on the Coromandel. Pateke were widespread on the Coromandel in the early 1900s but with the spread of predators less than 20 were surviving in the Port Charles area near the top of the Coromandel.

Thanks to the 2000 Audit the release of captive reared Pateke commenced on the Coromandel in 2003 and ended in 2007 with 250 Pateke released. This release was supported by the existing and extensive predator control programme in the Moehau Ranges in operation since 1999 and by 2013 there are several hundred Kiwi surviving in the ranges. An extensive predator control programme for Pateke at Port Charles and environs was launched in 2001, with a high level of survival of both released and wild teal.

And from 20 to 750 Pateke on the Coromendel is an incredible success story and clearly confirmed precisely what the TV Presenter stated in 1999 – “Provide brown teal with a predator free environment and they will live for 24-years”! The level of survival of released birds, their adaptability and their breeding success, coupled with major predator control programmes, no duck hunting and outstanding support from the local Port Charles community, including farmers, is an outstanding example of what can be achieved in a short space of time. Brown teal are now being observed in an increasing number in many areas of the Peninsula with one flock of 180 being counted in 2012 at Waikawau Bay.

istorically, a peninsula has proven to be readily defensible against predators and with ongoing predator control on the Coromandel Peninsula a population of over 2000 Pateke could be achieved.

Besides well organised and intensive predator control on the Coromandel the support of the local farming community and residents has been an intrinsically important part of the success, with a number of land owners creating quality Pateke habitat and the locals carrying out much of the predator control work.

In addition financial contributions from The Moehau Environmental Group, Banrock Station Wines of Adelaide, Isaac Wildlife Trust, DUNZ, DOC, Brown Teal Conservation Trust and, critically important to the whole programme - the Pateke captive breeders - all helped ensure the success of the Coromandel re-establishment programme.

There is still much to be done before Pateke are anywhere near being saved from extinction and a future for the species is assured. DUNZ can be justly proud of its achievements with Pateke.

Next issue of Flight - The Positives and negatives of Pateke recovery programme.

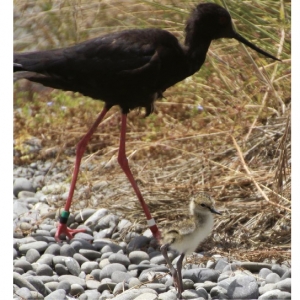

Record results for black stilt

A record number of endangered black stilts (kakī) were released in the Mackenzie Basin in spring after the most productive captive breeding season on record.

Overall 184 kakī were hatched and reared for release by the Department of Conservation, including 49 by the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT).

In 1981, when the population plummeted to only 23 known birds in the wild, measures were taken to manage this tiny population.

Kakī, once widespread throughout wetlands and braided rivers throughout the South Island and lower North Island, remain categorised as critically endangered and are the rarest wading birds in the world. Their range is limited to the harsh environment of the Mackenzie and Waitaki basins, often snowbound through the winter months and drought affected during summer.

Controlling stoats, ferrets and feral cats across the Tasman Valley is critical for kakī to survive in their natural habitat.

Without predator control, fewer than 30 per cent of young birds survive. In areas with trapping, the survival rate is 50 per cent.

Captive breeding facilities operated by ICWT and DOC are an essential conservation tool to bring the species back from the brink of extinction, with genetic management one of the multiple tools used to optimise captive breeding outcomes.

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust continues the conservation work of Sir Neil and Lady Diana Isaac who bequeathed all their assets into the self-funding charitable trust, to continue their legacy and commitment to conservation.

▪ Catherine Ott is the administration manager for the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

Pukaha releases shore plovers

Fabulous Whio

The black stilt/kaki

A unique wader on the brink

Once the common stilt of New Zealand, the endemic black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae) remains critically endangered and is considered the world’s rarest wader, despite over 30 years of intensive conservation management.

Black stilts have a distinctive elongated neck, jet-black plumage, red eyes, long red legs and a thin black bill. Due to their variable plumage, juveniles and sub-adults can be easily overlooked amongst pied stilts, while hybrids add to the confusion. Juveniles in their first winter plumage have a black back, smudgy grey hind neck and variable dark markings on the flank. The plumage darkens during their second summer moult, and by mid-summer they are predominantly black. Contact calls are a single or repeated “yep”. Territorial birds are noisy, having a higher pitched and more penetrating call than the pied stilt.

Typical black stilt habitat consists of wideopen braided riverbeds and associated nearby wetlands, ponds and shallow lake edges. During flooding more stable side-streams, swamps and ponds are favoured. Nesting territories are located in areas with abundant food, such as shallow river channels rich in aquatic invertebrates. Outside the breeding season black stilts move locally within the Mackenzie Basin, but small numbers frequent the Canterbury coast (Lakes Wainono and Ellesmere), and Kawhia and Kaipara Harbours in the North Island.

At the time of European settlement this now exceptionally rare wader was widespread throughout New Zealand and bred at North Island locations until the late 19th century. Settlement intensified swiftly, exotic plants and animals were introduced, wetlands were drained and rivers were channelised. The environment changed rapidly and black stilt numbers decreased swiftly to devastatingly low levels. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago by the 1950s, South Canterbury and North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s. The breeding population is now restricted to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south. In 1981 the population fell to just 23 birds, which increased to 55 birds by 2005 and 85 birds in 2010. Before the annual release of captive birds, the free-living population was ~130 birds in 2012. We are now in 2016 and the population continues to increase, but only ever so slowly.

Today black stilts face a wide range of threats including habitat loss and modification (agriculture, hydroelectric development, weed invasions, flooding), introduced mammalian predators (feral cats, rats, hedgehogs and mustelids), avian predation (Australasian harrier and black backed gull), human disturbance (recreational river users disturb nesting adults and crush eggs/chicks), and pied stilt hybridisation (now a lesser issue). The development of irrigation has seen significant changes in land use, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in considerable habitat loss.

To address these threats and increase numbers, the Department of Conservation initiated the Kaki Recovery Programme in 1981. The programme has produced great results by focusing on wild egg collection, artificial incubation, captive rearing of chicks for release, predator control to protect wild populations, research and promoting awareness.

Only two captive facilities globally breed black stilts for release into the wild – the Department of Conservation in Twizel and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust in Christchurch. To date the Trust has played a pivotal role in black stilt conservation with 45 birds housed per season. Each season three to four clutches are collected from captive breeding pairs. First, second and third clutches are transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching, while the last clutches remain with pairs at the Trust. Older chicks and juveniles then transfer from Twizel to the Trust for preconditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. This process is vital for black stilt survival and resumes each breeding season at both facilities. The Trust aims to expand its operations by constructing separate incubation and brooder facilities by 2020, which will result in fewer transfers and enable more chicks to be held on site.

While intensive conservation management has succeeded at increasing black stilt numbers, the species continues to struggle and remains critically endangered. Annual releases and predator control have prevented black stilt extinction; nevertheless various challenges remain with managing wild populations. Releases on the mainland are limited to certain sites and continue to be a numbers game. In New Zealand many threatened species benefit from predator-free island translocations; however there are no predator-free island habitats with braided river systems. On average 120 chicks (including wild collected eggs), are released annually, slowly increasing the population. However the post-release survival rate is only 33 percent with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. The species long-term survival therefore remains highly dependent on long-term captive breeding efforts and predator control.

How you can help

- Follow the River Care Code when visiting riverbeds. • Ground nesting birds, their eggs and chicks are almost impossible to see. Do not drive on riverbeds from August to December. • Birds swooping, circling or calling loudly likely have nests nearby. Move away so they can return to them, or their eggs and chicks may die.

- A dog running loose can wreak havoc. Leave dogs at home or on leads.

- Jet boats disturb birds and can wash away nests near the water’s edge. The speed limit for boats is 5 knots within 200 m of a bank.

- Place bells on your cat’s collar and keep it indoors at dusk, night and dawn.

- Plant natives and trap introduced predators on your property.

Sabrina Luecht

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

Endangered native beetle

Endangered native beetle threatened by rabbits and redbacks

An “unholy alliance” between rabbits and Australian redback spiders is threatening the existence of an endangered New Zealand species, a study by AgResearch has shown.

Carried out with the Department of Conservation (DOC) and University of Otago, the study has illustrated the struggle for the ongoing survival of the Cromwell chafer beetle – a nationally endangered native species that can now only be found in the 81 hectare Cromwell Chafer Beetle Nature Reserve between Cromwell and Bannockburn, in Central Otago.

The study found numerous rabbit holes that shelter the rabbits were also proving ideal spaces for the redback spiders to establish their webs. Investigation of those webs in the rabbit holes found the Cromwell chafer beetle was the second-most commonly found prey of the spiders.

“Of course the rabbits and spiders aren’t actually plotting to bring about the demise of the chafer beetle, but these findings do give a fascinating insight into the almost accidental relationships that can develop between species in the natural world, and how that can impact on other species,” said AgResearch Principal Scientist Dr Barbara Barratt.

“Otago University students doing research in the area found that 99 percent of the spiders had built their webs in the rabbit holes. We don’t know exactly how many of the chafer beetles there are left because they are not easy to find, but research into larval densities tells us the numbers are low. It does appear the redback spider, which has established populations in two locations in New Zealand since the 1980s, has been increasing in number over time, and this increases the risks for the beetle population.

“What we were able to show in our research was that filling in those rabbit holes was an effective way of eliminating the presence of the redback spiders at the treated sites, and therefore reducing the rate of the chafer beetle being preyed upon.

”As a result of the research, DOC has carried out a programme to break down old rabbit holes and hummocks in the reserve to destroy spider nests, and also does regular rabbit control. An annual survey for beetle larvae with AgResearch will show whether these actions are having an effect.

“We will survey for beetle larvae next summer to see what effect reducing redback spider nests is having on the Cromwell chafer beetle,” said DOC Ecology Technical Advisor Bruce McKinlay. “Hopefully we’ll find the beetle population has increased with fewer falling prey to this introduced venomous spider.”

The Cromwell chafer beetle (Prodontria lewisi) is a large flightless beetle that lives underground in the sandy soils of the Cromwell river terrace. In spring and summer adult beetles emerge from the ground at night to feed on plants and to breed.

Jarrod Booker

AgResearch External Communications Manager

Spring Has Sprung

The 2017/18 breeding season has begun and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT) once again reached its busy rearing phase.

Early October saw the collection of the first clutch of critically endangered New Zealand shore plover eggs for artificial incubation. Critically endangered black stilt/kaki pairs had also begun laying eggs.

ICWT is happy to report that three clutches have been incubated by critically endangered orange-fronted parakeet breeding pairs, as well as eight healthy chicks presently being raised. (see page 9).

The first South Island blue duck/whio ducklings hatched, while North Island ducklings hatched soon after. Meanwhile five brown teal/pateke pairs have hatched ducklings and more will be on the way.

ICWT’s reptiles are becoming more active with the warming weather, meaning tuatara, Otago skinks and grand skinks will be breeding as well.

As always, ICWT’s ambitious native planting programme across the Isaac Conservation Park and the Otukaikino River restoration site continues; while salvaged historic buildings continue to be restored to their former glory in the Heritage Village.

For more information see:

http://www.isaacconservation.org.nz/

https://www.facebook.com/ICWTNZ/

Sabrina Luecht,

Wildlife Project Administrator,

ICWT

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki (Himantopus novaezelandiae) is one of the most endangered birds globally and remains the rarest wading bird in the world, despite over 30 years of intensive management. The species is only found in New Zealand’s South Island and is considered a Canterbury icon.

The black stilt was formerly widespread throughout the New Zealand mainland, and was still breeding at North Island locations in the late 19th century. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago in the 1950s, South Canterbury-North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s.

Today the black stilt’s breeding distribution is limited to braided rivers and wetlands in the upper Waitaki River valley of the Mackenzie Basin. Breeding pairs are now confined to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south.

The Department of Conservation (DOC) has managed the Kaki Recovery Programme since 1981, when the population declined to just 23 adult birds. The programme aims to increase the population by wild egg collection and captive rearing, captive breeding, predator control, and increasing public awareness. By 1991 the wild population still only consisted of 31 adult birds, while in 2010 the number had increased to 85 birds, and 130 birds in 2012. However, today there are still only 106 black stilts remaining in the wild and the species remains on the brink of extinction.

This is due to a number of challenges from a range of threats: introduced predators, habitat degradation, habitat loss, hybridisation with pied stilt, and human recreational disturbance. Intensive predator control is undertaken due to a whole suite of introduced mammalian predators, as well as native avian predators. These predators are prevalent across the area and are subject to major fluctuations. The development of irrigation has also seen major changes in land use in the Mackenzie Basin, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in extensive habitat loss.

DOC and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT) are the only two organisations globally to captive breed this exceptionally rare species, in order to halt extinction. Annual releases into the wild of captive bred birds and predator control have undoubtedly prevented the black stilt from becoming extinct in the wild. Without this intensive conservation effort, the species would be extinct in less than 8 years.

ICWT therefore plays a pivotal role in black stilt conservation, with up to 61 birds per season housed in two custom-built aviary complexes. ICWT’s captive pairs produce three to four clutches each season, with all eggs generally transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching. More recently ICWT has also been hand-rearing chicks from Twizel, whilst a snow-damaged aviary there minimized capacity. Each season up to 50 juveniles are held at ICWT for pre-release conditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. At present there are 121 juveniles in captivity at DOC and ICWT, which will be released in August.

Releasing black stilts on the mainland remains difficult and continues to be a numbers game, even with intensive predator control and monitoring. Many of New Zealand’s threatened species benefit from translocations to predator-free offshore islands; however there are no islands with suitable braided river habitats for black stilt transfers, making releases confined to very limited sites. On average 120 chicks (from wild collected and captive bred eggs) are released annually, slowly increasing the fragile population. However the post-release survival rate is still only 33%, with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. While the species may be rebounding from the brink of extinction (compared to the all-time low population in 1981), the black stilt still has a long way to go, with long-term survival remaining dependent on captive breeding efforts and rigorous predator control.

For these reasons ICWT intends to expand its black stilt capacity by 2025, by building a separate incubation and brooder room facility. This will broaden ICWT’s hand rearing capability and increase overall output for the Kaki Recovery Programme.

DOC has also just received $500,000 from Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), which will fund the replacement of the flight aviary which was destroyed in a 2015 snowstorm. This means the programme will again be able to rear and release an additional 60 black stilt juveniles annually

Sabina Lluecht - The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

On the Scent - Bittern

listening posts – that was a lot of noise and a lot of birds. So many that observers regularly complained that they couldn’t keep track of them all.