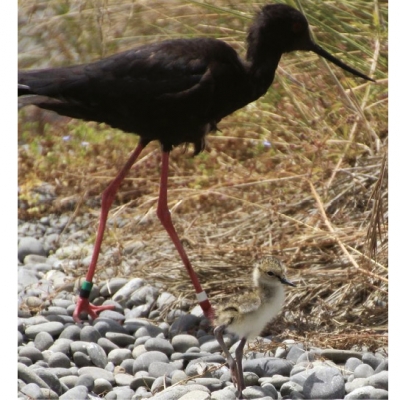

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki (Himantopus novaezelandiae) is one of the most endangered birds globally and remains the rarest wading bird in the world, despite over 30 years of intensive management. The species is only found in New Zealand’s South Island and is considered a Canterbury icon.

The black stilt was formerly widespread throughout the New Zealand mainland, and was still breeding at North Island locations in the late 19th century. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago in the 1950s, South Canterbury-North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s.

Today the black stilt’s breeding distribution is limited to braided rivers and wetlands in the upper Waitaki River valley of the Mackenzie Basin. Breeding pairs are now confined to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south.

The Department of Conservation (DOC) has managed the Kaki Recovery Programme since 1981, when the population declined to just 23 adult birds. The programme aims to increase the population by wild egg collection and captive rearing, captive breeding, predator control, and increasing public awareness. By 1991 the wild population still only consisted of 31 adult birds, while in 2010 the number had increased to 85 birds, and 130 birds in 2012. However, today there are still only 106 black stilts remaining in the wild and the species remains on the brink of extinction.

This is due to a number of challenges from a range of threats: introduced predators, habitat degradation, habitat loss, hybridisation with pied stilt, and human recreational disturbance. Intensive predator control is undertaken due to a whole suite of introduced mammalian predators, as well as native avian predators. These predators are prevalent across the area and are subject to major fluctuations. The development of irrigation has also seen major changes in land use in the Mackenzie Basin, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in extensive habitat loss.

DOC and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT) are the only two organisations globally to captive breed this exceptionally rare species, in order to halt extinction. Annual releases into the wild of captive bred birds and predator control have undoubtedly prevented the black stilt from becoming extinct in the wild. Without this intensive conservation effort, the species would be extinct in less than 8 years.

ICWT therefore plays a pivotal role in black stilt conservation, with up to 61 birds per season housed in two custom-built aviary complexes. ICWT’s captive pairs produce three to four clutches each season, with all eggs generally transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching. More recently ICWT has also been hand-rearing chicks from Twizel, whilst a snow-damaged aviary there minimized capacity. Each season up to 50 juveniles are held at ICWT for pre-release conditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. At present there are 121 juveniles in captivity at DOC and ICWT, which will be released in August.

Releasing black stilts on the mainland remains difficult and continues to be a numbers game, even with intensive predator control and monitoring. Many of New Zealand’s threatened species benefit from translocations to predator-free offshore islands; however there are no islands with suitable braided river habitats for black stilt transfers, making releases confined to very limited sites. On average 120 chicks (from wild collected and captive bred eggs) are released annually, slowly increasing the fragile population. However the post-release survival rate is still only 33%, with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. While the species may be rebounding from the brink of extinction (compared to the all-time low population in 1981), the black stilt still has a long way to go, with long-term survival remaining dependent on captive breeding efforts and rigorous predator control.

For these reasons ICWT intends to expand its black stilt capacity by 2025, by building a separate incubation and brooder room facility. This will broaden ICWT’s hand rearing capability and increase overall output for the Kaki Recovery Programme.

DOC has also just received $500,000 from Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), which will fund the replacement of the flight aviary which was destroyed in a 2015 snowstorm. This means the programme will again be able to rear and release an additional 60 black stilt juveniles annually

Sabina Lluecht - The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

Image Gallery

https://ducks.org.nz/flight-magazine/item/21-the-critically-endangered-black-stilt-kaki#sigProIddf8c0b0ff7