Displaying items by tag: Kaki

Protecting our kakī

As a ranger based in Twizel the main part of my job is supporting the Kakī Recovery Programme.

population in the wild and ensure this special bird is not lost for future generations.

As part of a small team of four permanent and a few seasonal staff, my responsibilities involve managing kakī in the wild. This includes counting how many adults are out there; traipsing up and down numerous braided rivers in the Mackenzie Basin searching for breeding pairs; observing and interpreting behaviour; finding their nests; reading leg bands and collecting eggs fromthe wild to bring back to the captive rearing facility in Twizel.

At 3–9 months they are released into the wild. Rearing them in captivity significantly increases their chances of survival by

preventing predation when they are most vulnerable and it also gets them through their first winter, which can be tough for young birds in the wild.

Record results for black stilt

A record number of endangered black stilts (kakī) were released in the Mackenzie Basin in spring after the most productive captive breeding season on record.

Overall 184 kakī were hatched and reared for release by the Department of Conservation, including 49 by the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT).

In 1981, when the population plummeted to only 23 known birds in the wild, measures were taken to manage this tiny population.

Kakī, once widespread throughout wetlands and braided rivers throughout the South Island and lower North Island, remain categorised as critically endangered and are the rarest wading birds in the world. Their range is limited to the harsh environment of the Mackenzie and Waitaki basins, often snowbound through the winter months and drought affected during summer.

Controlling stoats, ferrets and feral cats across the Tasman Valley is critical for kakī to survive in their natural habitat.

Without predator control, fewer than 30 per cent of young birds survive. In areas with trapping, the survival rate is 50 per cent.

Captive breeding facilities operated by ICWT and DOC are an essential conservation tool to bring the species back from the brink of extinction, with genetic management one of the multiple tools used to optimise captive breeding outcomes.

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust continues the conservation work of Sir Neil and Lady Diana Isaac who bequeathed all their assets into the self-funding charitable trust, to continue their legacy and commitment to conservation.

▪ Catherine Ott is the administration manager for the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

The black stilt/kaki

A unique wader on the brink

Once the common stilt of New Zealand, the endemic black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae) remains critically endangered and is considered the world’s rarest wader, despite over 30 years of intensive conservation management.

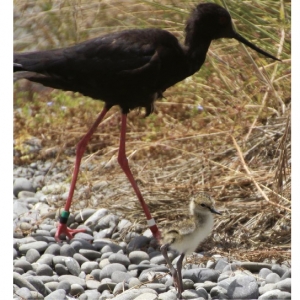

Black stilts have a distinctive elongated neck, jet-black plumage, red eyes, long red legs and a thin black bill. Due to their variable plumage, juveniles and sub-adults can be easily overlooked amongst pied stilts, while hybrids add to the confusion. Juveniles in their first winter plumage have a black back, smudgy grey hind neck and variable dark markings on the flank. The plumage darkens during their second summer moult, and by mid-summer they are predominantly black. Contact calls are a single or repeated “yep”. Territorial birds are noisy, having a higher pitched and more penetrating call than the pied stilt.

Typical black stilt habitat consists of wideopen braided riverbeds and associated nearby wetlands, ponds and shallow lake edges. During flooding more stable side-streams, swamps and ponds are favoured. Nesting territories are located in areas with abundant food, such as shallow river channels rich in aquatic invertebrates. Outside the breeding season black stilts move locally within the Mackenzie Basin, but small numbers frequent the Canterbury coast (Lakes Wainono and Ellesmere), and Kawhia and Kaipara Harbours in the North Island.

At the time of European settlement this now exceptionally rare wader was widespread throughout New Zealand and bred at North Island locations until the late 19th century. Settlement intensified swiftly, exotic plants and animals were introduced, wetlands were drained and rivers were channelised. The environment changed rapidly and black stilt numbers decreased swiftly to devastatingly low levels. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago by the 1950s, South Canterbury and North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s. The breeding population is now restricted to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south. In 1981 the population fell to just 23 birds, which increased to 55 birds by 2005 and 85 birds in 2010. Before the annual release of captive birds, the free-living population was ~130 birds in 2012. We are now in 2016 and the population continues to increase, but only ever so slowly.

Today black stilts face a wide range of threats including habitat loss and modification (agriculture, hydroelectric development, weed invasions, flooding), introduced mammalian predators (feral cats, rats, hedgehogs and mustelids), avian predation (Australasian harrier and black backed gull), human disturbance (recreational river users disturb nesting adults and crush eggs/chicks), and pied stilt hybridisation (now a lesser issue). The development of irrigation has seen significant changes in land use, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in considerable habitat loss.

To address these threats and increase numbers, the Department of Conservation initiated the Kaki Recovery Programme in 1981. The programme has produced great results by focusing on wild egg collection, artificial incubation, captive rearing of chicks for release, predator control to protect wild populations, research and promoting awareness.

Only two captive facilities globally breed black stilts for release into the wild – the Department of Conservation in Twizel and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust in Christchurch. To date the Trust has played a pivotal role in black stilt conservation with 45 birds housed per season. Each season three to four clutches are collected from captive breeding pairs. First, second and third clutches are transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching, while the last clutches remain with pairs at the Trust. Older chicks and juveniles then transfer from Twizel to the Trust for preconditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. This process is vital for black stilt survival and resumes each breeding season at both facilities. The Trust aims to expand its operations by constructing separate incubation and brooder facilities by 2020, which will result in fewer transfers and enable more chicks to be held on site.

While intensive conservation management has succeeded at increasing black stilt numbers, the species continues to struggle and remains critically endangered. Annual releases and predator control have prevented black stilt extinction; nevertheless various challenges remain with managing wild populations. Releases on the mainland are limited to certain sites and continue to be a numbers game. In New Zealand many threatened species benefit from predator-free island translocations; however there are no predator-free island habitats with braided river systems. On average 120 chicks (including wild collected eggs), are released annually, slowly increasing the population. However the post-release survival rate is only 33 percent with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. The species long-term survival therefore remains highly dependent on long-term captive breeding efforts and predator control.

How you can help

- Follow the River Care Code when visiting riverbeds. • Ground nesting birds, their eggs and chicks are almost impossible to see. Do not drive on riverbeds from August to December. • Birds swooping, circling or calling loudly likely have nests nearby. Move away so they can return to them, or their eggs and chicks may die.

- A dog running loose can wreak havoc. Leave dogs at home or on leads.

- Jet boats disturb birds and can wash away nests near the water’s edge. The speed limit for boats is 5 knots within 200 m of a bank.

- Place bells on your cat’s collar and keep it indoors at dusk, night and dawn.

- Plant natives and trap introduced predators on your property.

Sabrina Luecht

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki (Himantopus novaezelandiae) is one of the most endangered birds globally and remains the rarest wading bird in the world, despite over 30 years of intensive management. The species is only found in New Zealand’s South Island and is considered a Canterbury icon.

The black stilt was formerly widespread throughout the New Zealand mainland, and was still breeding at North Island locations in the late 19th century. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago in the 1950s, South Canterbury-North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s.

Today the black stilt’s breeding distribution is limited to braided rivers and wetlands in the upper Waitaki River valley of the Mackenzie Basin. Breeding pairs are now confined to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south.

The Department of Conservation (DOC) has managed the Kaki Recovery Programme since 1981, when the population declined to just 23 adult birds. The programme aims to increase the population by wild egg collection and captive rearing, captive breeding, predator control, and increasing public awareness. By 1991 the wild population still only consisted of 31 adult birds, while in 2010 the number had increased to 85 birds, and 130 birds in 2012. However, today there are still only 106 black stilts remaining in the wild and the species remains on the brink of extinction.

This is due to a number of challenges from a range of threats: introduced predators, habitat degradation, habitat loss, hybridisation with pied stilt, and human recreational disturbance. Intensive predator control is undertaken due to a whole suite of introduced mammalian predators, as well as native avian predators. These predators are prevalent across the area and are subject to major fluctuations. The development of irrigation has also seen major changes in land use in the Mackenzie Basin, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in extensive habitat loss.

DOC and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT) are the only two organisations globally to captive breed this exceptionally rare species, in order to halt extinction. Annual releases into the wild of captive bred birds and predator control have undoubtedly prevented the black stilt from becoming extinct in the wild. Without this intensive conservation effort, the species would be extinct in less than 8 years.

ICWT therefore plays a pivotal role in black stilt conservation, with up to 61 birds per season housed in two custom-built aviary complexes. ICWT’s captive pairs produce three to four clutches each season, with all eggs generally transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching. More recently ICWT has also been hand-rearing chicks from Twizel, whilst a snow-damaged aviary there minimized capacity. Each season up to 50 juveniles are held at ICWT for pre-release conditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. At present there are 121 juveniles in captivity at DOC and ICWT, which will be released in August.

Releasing black stilts on the mainland remains difficult and continues to be a numbers game, even with intensive predator control and monitoring. Many of New Zealand’s threatened species benefit from translocations to predator-free offshore islands; however there are no islands with suitable braided river habitats for black stilt transfers, making releases confined to very limited sites. On average 120 chicks (from wild collected and captive bred eggs) are released annually, slowly increasing the fragile population. However the post-release survival rate is still only 33%, with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. While the species may be rebounding from the brink of extinction (compared to the all-time low population in 1981), the black stilt still has a long way to go, with long-term survival remaining dependent on captive breeding efforts and rigorous predator control.

For these reasons ICWT intends to expand its black stilt capacity by 2025, by building a separate incubation and brooder room facility. This will broaden ICWT’s hand rearing capability and increase overall output for the Kaki Recovery Programme.

DOC has also just received $500,000 from Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), which will fund the replacement of the flight aviary which was destroyed in a 2015 snowstorm. This means the programme will again be able to rear and release an additional 60 black stilt juveniles annually

Sabina Lluecht - The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust