Super User

Restoring the balance for whio

Horizons Regional Councillors joined DOC representatives and iwi at Blue Duck Station in February 2017 for a whio release, during a tour of the northern parts of the ManawatuWhanganui Region. Blue Duck Station set within the Kia Wharite project, has seen Horizons, DOC, Whanganui iwi and

private landowners working in the private lands and remote forests around Whanganui National Park to improve land, water and biodiversity, while enhancing community and economic wellbeing. Kia Wharite is one of the largest projects of its kind in New Zealand in scale and scope.

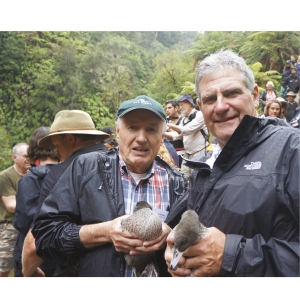

Back in February, way before the weather bomb hit Blue Duck Station, (see page 7) Horizons Regional Councillors joined the Department of Conservation (DOC) deputy director general operations, Mike Slater, and iwi representatives for the release of 14 whio at Blue Duck Station.

The whio release was a hands-on opportunity to show how Kia Wharite, a collaborative biodiversity project in the Whanganui/ Ruapehu districts, is directly contributing to the survival of native species.

Since 2008, Horizons, DOC, Whanganui iwi and private landowners have been working in the private lands and remote forests around Whanganui National Park to improve land, water and biodiversity health, while enhancing community and economic wellbeing. Kia Wharite is one of the largest projects of its kind in New Zealand in terms of scale and scope.

The Kia Wharite project spans over 180,000 hectares and includes a mixture of private land and parts of the Whanganui National Park, the second largest lowland forest in the North Island. This remote area is home to the largest population of Western North Island brown kiwi and plays host to many native bird and plant species.

Possums, goats, stoats and other predators have threatened the health of the forest and put the long-term future of its inhabitants in jeopardy.

Horizons Councillor Bruce Rollinson said as part of the project extensive possum control operations have been undertaken by Horizons and OSPRI on rated land, and DOC on crown land. OSPRI have signalled a phased withdrawal from areas inside the project sites, as these areas are declared TB free. Currently approximately 150,000 hectares of land has regular possum control undertaken in the project area.

This work, alongside pest and weed control, protecting bush and wetlands and monitoring threatened native species, is also why it was possible to release 14 whio into the Kaiwhakauka Stream. Here, whio are protected on the river through a network of traps managed by Blue Duck Station volunteers to target stoats, said Cr Rollinson.

Predator control is carried out in the wider whio security site by Horizons and DOC; over 85 km of trap lines are in place along the Retaruke and Manganui o te Ao rivers, providing necessary protection for whio.

Department of Conservation deputy director general operations Mike Slater said with a population of fewer than 3000, this national whio security site is one of eight locations identified across the country as being essential for whio recovery.

With the support of Genesis Energy, DOC has been able to double the number of fully secure whio breeding sites, boost pest control efforts and enhance productivity and survival of these rare native ducks. The ultimate goal of this security site is to achieve protection to 50 breeding pairs, said Mr Slater.

Whio are adapted to live on fast-flowing rivers so finding them means you have also found clean, fast-flowing water with a good supply of insects. This makes whio important indicators of ecosystem health, they only exist where there is high quality, clean and healthy waterways.

It is not just whio and the environment that benefit from the project. Horizons and DOC believe there are positive economic returns to be had from the project. Blue Duck Station is the most obvious example.

The sheep and beef cattle farm, located 55km south-west of Taumarunui, is set on 2915 hectares of medium to steep hill countryDuck Station owner and manager Dan Steele said grazing areas have been deliberately offset by native bush and manuka. “Through the Kia Wharite project, we have

worked closely with Horizons and DOC to develop a sustainable land plan, and fence ofselected farm areas to protect native fauna and flora,” said Dan Steele.

“The Station has approximately 450 traps for stoats, mustelids, feral cats, rats, mice and hedgehogs; all enemies of the blue duck as well as other native species. In partnership with Kia Wharite, we maintain and reset the traps approximately every two weeks; this is undertaken mainly by our olunteers or ecowarriors as we call them.

“Embracing the environment in this way provided the perfect place to set up a lodge and tourism operation. In a relatively short time we have grown to approximately 8000 visitors a year, many of whom become ecowarriors during their stay,” said Dan Steele.

Cr Rollinson said Kia Wharite is proving to be a successful approach, with the project already exceeding some of its goals. “It shows what can be accomplished when organisations join forces and work collaboratively.”

Keep a weather eye on the birds

Back in March 2017, near Pokeno on the F&G McKenzie Wetland Block near Pokeno, one hour south of Auckland off SH1 we were banding grey teal there. If DU members could keep an eye out for these I would be pleased to hear about them.

Now for BOW – this is a pond specially reserved for people who pass our course of how to shoot clay targets, dress (pluck) game, tie trout flies, cast a trout rod and there’s a nice salmon meal in a tent to finish with.

The Dean Block is a F&G wetland near Pokeno and BOW pond is part of that. There’s about 50 grey teal nest boxes there and more on the adjoining McKenzie Block.

BOW means Becoming an Outdoor Woman. The lady who did this, Shonagh Lindsay, has since moved on, which means the programme Grey Teal 1: Good spot – Fish and Game. Dabchicks: Dabchicks at BOW pond. is currently suspended. We took women of all ages and shooting coaches Brian Thompson or Bill McLeod taught them how to shoot a shotgun at clay targets. I taught them how to dress a duck and then cooked it for them, (Schnitzel-style). The Auckland Anglers club taught them how to fly-cast with a trout rod. Sally Spiers and her daughter showed them how to tie a trout fly in the tent, (they fished the one they tied themselves – a Woolly Buggar – that’s actually what it is called, (it was Sally Spiers who chose it). We then gave them a chance to catch a fish near Waikino, (near Waihi).

It was a popular two-day programme, and we did feed them salmon in a F&G tent, Paul Matos was the professional chef who donated his time for many of these. But eventually everyone who wanted to give it a go did so and bookings in Auckland dried up. Northland Fish & Game also did some for several years with equal success. We were strongly hoping other F&G regions would pick up the proven programme.

I think the main idea is that many woman would like to give these things a go with their men-folk but perhaps lack confidence. We thought if we taught them the basics, they’d join in. After all, if their father, husband, boyfriend or brother already had the gear, the know-how and the places to go. We thought the inspired, initiated and more confident women could now go with them. The feedback was very positive and it seemed everyone, trainers and trainees, had a lot of fun doing it.

John Dyer

2017 DUNZ Photo Competition top shots

Whio in decline

Whio in decline…

The whio (blue duck) is one of New Zealand’s ancient endemic waterfowl species and is classified as Threatened (Nationally Vulnerable) in the New Zealand Threat Classification System 2012, and listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

North Island and South Island whio populations are genetically distinct (though they are not described as sub-species) and are treated as separate management units. The whio has experienced rapid declines (particularly in the South Island) in abundance and distribution, nowhere common. It lives at low densities in severely fragmented populations. The most recent estimate of total population numbered 1200 pairs at most.

The most notable decline driver comes from introduced mammalian predators, with predation of eggs, young and incubating females. Stoats are the most significant threat and stoat control is a main focus of management activities.

The blue duck’s widespread decline throughout South Island beech forests areas has highlighted the insidious effects of mast-seeding beech trees, which result in great predation pressure, as rodent populations explode, causing a lagged increase in stoat populations which seek alternative prey when rodent numbers crash. A malebiased sex-ratio throughout the range, indicates that predation during incubation is significant.

One of the major conservation management tools for whio is captive breeding for release into the wild. The blue duck has been held in captivity for many years, and its husbandry requirements are understood. The aim is to maximise productivity of the captive breeding programme, and ensure that captive-bred ducklings are released at the highest priority sites. Captive breeding has proven highly effective, and is vital in aiding the recovery programme with the re-establishment and rebuilding of viable populations throughout the former range.

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust provides the largest output of blue duck juveniles annually, with its waterfowl aviaries being the most successful captive breeding enclosures in New Zealand for North Island blue duck. The Trust currently holds two North Island blue duck breeding pairs. These breeding pairs can lay up to three clutches per season, with an average of six eggs per clutch. All eggs are collected for incubation and hand rearing.

The Trust is a significant participant in the WHIONE programme, which consists of retrieving wild eggs each breeding season from South Island pairs for artificial incubation and rearing in captivity, with a subsequent release of juveniles once fledglings have been hardened in our fast water facilities and are at a lower risk of predation. Releases take place in natal territories or at new sites around the South Island to increase numbers and genetic diversity across sites or re-establish lost populations. Since 2016 the Trust has been retaining cohorts of South Island blue duck juveniles for flock mating, to initiate a captive breeding population across several South Island facilities. The Trust will move out of North Island birds and hold three pairs of the South Island blue duck.

Each season for the last 12 years, the Trust has also received North Island blue duck juveniles bred by other captive institutions nationwide, which are transferred for pre-conditioning in fast flowing raceways prior to release into the wild.

Sabrina Luecht

Wildlife Project Administrator

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

Isaac Conservation Trust

The Isaac Conservation and

Wildlife Trust

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust, established in 1977 continues the land rehabilitation and conservation work of Sir Neil and Lady Diana Isaac.

The Trust is self-funding and does not solicit for monies. It is the assets, bequeathed to the Trust from Sir Neil and Lady Isaac that provide the income to continue their philanthropic contribution to conservation.

The main focuses are the conservation of endangered native flora and fauna, the conservation of heritage buildings and the study of conservation through education and research. This study of conservation and the environment is embodied by funding two post graduate scholarships annually, at both Canterbury and Lincoln Universities.

Specialised captive breeding of New Zealand native birds, reptiles and fish, with the aim of reintroduction into the wild, is carried out to stabilise and reverse declines in at-risk species. The Trust currently holds New Zealand shore plover, orange-fronted parakeet, red-crowned parakeet, black stilt,

blue duck, brown teal, Cook Strait tuatara, grand skink, Otago skink and Canterbury mudfish.

The Trust also breeds Cape Barren geese and mute swan, which are donated to Ducks Unlimited New Zealand.

The Trust has decades of animal husbandry and captive breeding experience, specialising in New Zealand species on the brink of a high threat status. This area of the Isaac Conservation Park is off limits to the public due to the fragility of its inhabitants.

Lady Isaac was not just a wildlife conservationist, but also a conservationist of historic buildings. The development of the Isaac Heritage Village is comprised of 14 relocated historic Canterbury buildings.

Many of these unique and irreplaceable buildings (c.1860 to 1940), were threatened with demolition. The Heritage Village will eventually be open to the public. Revegetation of plants on the Isaac Conservation Park land includes a focus on the restoration of the Otukaikino River, feeding into the Waimakariri River. To date the Trust has fenced off waterways from stock, extensively cleared weeds, and planted over 45,000 eco-sourced natives. Along the corridor of native plants that now line the river, land has been set aside to provide a public walkway.

The Trust has been set up to exist in perpetuity to provide a benchmark in conservation, continuing the legacy of Sir Neil and Lady Isaac.

Catherine Ott

Fears for Whio

Fears for whio after weather bomb

February (2017) brought a highlight on the conservation calendar at Blue Duck Station – the release of 14 rare juvenile blue ducks (whio) into the Kaiwhakauka Stream.

After months of preparation in which the young whio were raised in captivity and prepared for life in the wild on an artificial stream, teams from Blue Duck Station, the Department of Conservation (DoC), Horizons, and Whio Forever saw the ducks off into their new home as part of a community event at Blue Duck Falls. A representative from the local iwi blessed the ducks before volunteers released them into the Kaiwhakauka, watching as they swam upstream into their new habitat. The long term aim is for the ducks to form breeding pairs along the length of the Kaiwhakauka stream, further strengthening the local whio population.

Unfortunately, the joy was short lived. In March a weather bomb wreaked havoc along the Kaiwhakauka. Over 100ml of rain fell in one day, causing flash floods and land slips that battered the Station. The environment around the Kaiwhakauka changed drastically – fallen trees and boulders littered the river, while flooding risked washing away the newly released whio. High water levels also threatened the whio’s ability to feed in the stream and with the stream bed turned upside down, it is unclear how much feed is left for the ducks.

While the damage is severe, the team at Blue Duck Station remain optimistic. In the coming months they will be assessing the impact and planning how best to help the ecosystem recover. Sightings of juveniles have continued in the surrounding areas since the floods, so hopes are high that habitats can be restored for further releases in the future and that Blue Duck Station will continue to be a haven for whio.

Maxine Ross, David Atkinson.

Wairio in action

A busy day at Wairio:

There was a digger on site to raise the walking track.

The success of retaining water in the wetland has required this work. Also the need to clear a few culverts to allow the water to flow more easily from Stage 4 (in the slightly higher ground in the north of the wetland) to the Stage 3 area. Though there is still plenty of work in progress and the need to equalise the water level.

There is new walking track signage made by DOC. That will be a big help for those interested in exploring the area.

And lastly, Stephen Hartley from Victoria University (with helpers Maxine, Veronica and our own Ross Cottle) starting a drone flight to record vegetation and water levels, principally in the Stage 3 research area.

What is a wetland

What is a wetland?

A wetland is an area of land whose soil is saturated with moisture either permanently or seasonally.

Such areas may also be covered partially or completely by shallow pools of water

Shore Plover breeding success at Pukaha Mount Bruce

The mission to save more than one endangered bird species has been enriched by last year’s successful breeding programmes at Pukaha Mount Bruce.

The Shore Plover programme saw over 10 birds transported from Pukaha Mt Bruce National Wildlife Centre to Motutapu Island in the Hauraki Gulf and Portland Island off the Mahia peninsula.

The shore plover is in a perilous position with fewer than 200 left in the wild and a history of conservation efforts being hampered by rat infestations. Shore plover were first spotted by observers on Captain Cook’s second voyage to New Zealand.

The shore plover is the most endangered bird reared and cared for at the centre. It is very susceptible to mammalian predators, even one rat can cause enormous damage.

Past Department of Conservation attempts to establish shore plover on Mana and Portland Islands were undone by what was thought to be a single rat in both cases.

The breeding and hatching of over 10 chicks at Pukaha had been a real triumph for the staff and wider conservation efforts.

In another success for the breeding programme, there were also over 10 pateke (brown teal) bred and hatched at the centre in the last breeding season.

The endangered ducks have a wild population of between 2,000 and 2,500 making them New Zealand’s most rare mainland waterfowl.

As well as great results in the Shore Plover and Pateke recovery programmes, the Whio (Blueduck) also produced more than one clutch of ducklings.

Pukaha’s new free flight aviary that opened in May 2016 enabled the breeding pair of Whio that call it home, to lay eggs which were then artificially incubated and hand-reared. Those ducks were sent to Turangi where they spent time in a purpose-built environment to prepare them for release to the wild.

The second clutch of eggs is allowed to stay with the parents and be raised naturally.

The theory is that by letting the parents raise them, the ducklings will be better parents when it is their time to breed.

By Illy McLean and Laura Hutchinson

The new green scene

Harnessing wetlands as green infrastructure solutions to our water woes

For one weekend every July in Canada, the village of St. Pierre-Jolys hosts the National Frog Jumping Championship. It’s part of the annual Frog Follies Festival. The thriving Franco-Manitoban community is also proud of its parks, a new residential compost pickup service and the Trans-Canada Trail that runs along the nearby Rat River. It’s about as green as it gets here. And it’s about to get greener.

Seeing wastewater through a green lens

Standing on a grassy berm overlooking St. Pierre-Jolys’ current wastewater treatment lagoon, Janine Wiebe points to an adjacent muddy field.

“In a few months, this field will be full of heavy equipment,” she says, smiling. The village’s chief administrative officer describes how their wastewater treatment system will expand to include a new tertiary treatment wetland.

Like all communities, St. Pierre-Jolys must anticipate the current and future needs of their wastewater treatment system. Future growth depends on it. Their system needs to remove pollutants, deliver clean water, handle increased volume and cope with the uncertain timing of storm water events.

Traditional, concrete treatment plants are expensive to build and maintain. St. PierreJolys found a better solution.

Staff from Native Plant Solutions (NPS) proposed the tertiary treatment wetland; a sustainable, cleaner, cost-effective and greener way to reduce nutrient levels in the village’s wastewater.

“In this system, a third cleansing cell – the wetland – is added to the primary and secondary treatment cells to reduce phosphorous levels,” says Glen Koblun, manager of NPS. NPS is a consulting branch of Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC) and a leader in science-based treatment wetland systems.

“There’s lower maintenance and management costs to this system compared to chemical or mechanical treatment options,” adds Koblun.

The treatment wetland system takes advantage of the natural functions of wetland plants – a process called phytoremediation – that transforms common pollutants into harmless by-products or essential nutrients. This comes from the sheer amount of biological activity that occurs in a wetland system including sunlight, wind, water, air, plants and soils.

“This project fits our vision,” says Wiebe. “We are leaving a legacy that will make it easier for future generations. It allows room for expansion and will cost less in the long run.”

Green infrastructure: it’s only natural

Green infrastructure is a buzz word that’s infiltrating conversations about making communities more resilient to disasters like floods. DUC research scientist Pascal Badiou, PhD, believes green infrastructure is essential. Wetlands, he says, are one of the most powerful systems available to us.

Traditional built infrastructure such as dry dams or water treatment systems serve an important role but typically address only one issue and come with high maintenance costs,” says Badiou.

“Green infrastructure, which includes natural areas, vegetation and wetlands, captures and treats stormwater and runoff at its source. It’s building with nature instead of concrete.”

Communities from coast to coast are finding that nature has an effective and efficient way to deal with wastewater: wetlands. These cost-effective, natural powerhouses provide benefits and services that reduce the need for costly built (grey) infrastructure such as dams, water diversions, water treatment plants and engineered carbon sinks. Green infrastructure like wetlands can also reduce pressure on and extend the life of grey infrastructure. ©DUC

Wetlands hold rainwater, snowmelt and floodwaters. They filter pollutants, store carbon, replenish groundwater, reduce erosion and provide habitat for wildlife as well as places for people to enjoy the outdoors.

“Other types of flood control are not able to deliver the additional benefits that wetlands provide,” says Badiou, who has conducted extensive research across the Prairies about the role of wetland drainage on water quality and quantity.

Seeing the green light through restoration

Getting people and governments to appreciate green infrastructure can be difficult. In Alberta, it took the devastating floods of June 2013 for the provincial government to reach a watershed moment. Southern Alberta was inundated. Downtown Calgary shut down. These events cost millions of dollars in damage.

The government responded with a number of funding programmes to address a wide range of recovery activities, including the Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Programme (WRRP). As its name implies, the WRRP aims to improve watershed functions to build greater long-term resiliency to droughts and floods. Resiliency would be improved through restoration, conservation, education and stewardship.

Traditional mitigation projects involve largescale construction or engineered structures (“grey” infrastructure). Watershed restoration supported by WRRP focuses on natural solutions. This includes conserving and restoring wetlands.

Tracy Scott, DUC’s head of industry and government relations in Alberta, and other DUC staff presented a business case for the use of wetland restoration for flood mitigation in southern Alberta. Their efforts helped inform the government’s development and implementation of the WRRP.

“The expansion of the WRRP programme to include natural green infrastructure was an excellent example of how we helped the Government of Alberta align wetland conservation with provincial and societal priorities, including Alberta’s Wetland Policy,” says Scott. “Few people recognise that the new Alberta Wetland Policy represents an important implementation tool to support Alberta’s flood, drought, water quality and biodiversity management goals.”

During the first round of the programme’s implementation in 2014, DUC has received $11.6 million to fund restoration of 1,380 acres (558 hectares) of wetlands in flood- and drought-prone areas in the southern part of the province

“A significant proportion of that money is going directly into the pockets of participating landowners, rewarding them for their contribution to ecosystem services, with the balance being used for the actual restoration work,” says Scott.

This puts the natural power of the landscape to work, instead of relying only on traditional engineered infrastructure,” says Scott. It’s a proactive approach that’s safeguarding the long-term future of water, wildlife and people across the province.

“The WRRP is the first chapter of DUC’s green infrastructure story in Alberta,” says Scott.

St. Pierre-Jolys CAO Janine Wiebe stands near the future site of the village’s tertiary treatment

wetland. The village consulted with DUC’s Native Plant Solutions on the project, will be an

additional treatment step to clean wastewater. This form of green infrastructure uses natural

wetland processes to clean the water before it enters the Rat River. ©Leigh Patterson

Pairing green with grey

As Alberta has learned, flood control is a key environmental benefit provided by wetlands. But little research exists specific to Ontario. The need to fill information gaps has escalated in recent years as the province has been hit with bigger storms and floods.

In 2016, DUC and several partners conducted research in the Credit River watershed, a densely-populated region vulnerable to extensive flooding. They used a hydrological model that quantified the consequences of wetland loss and gain on flooding under a variety of storm events.

This past fall, the results came in.

Not surprisingly, in modeling scenarios where researchers removed wetlands from the landscape, flooding was worse. When wetlands were restored the intensity of flooding diminished.

The research supports the idea that when combined with built infrastructure like storm water retention ponds, green infrastructure like wetlands can provide another layer of flood defence. Green infrastructure like wetlands can also reduce the pressure on and extend the life of grey infrastructure.

“The research identifies areas where wetland restoration will have the greatest impact on flood reduction,” says Mark Gloutney, PhD, DUC’s director of regional operations, eastern region. “DUC can work with municipalities, conservation authorities and others to better plan for extreme weather and flooding by helping build up their inventory of natural infrastructure assets, like wetlands.”

Building climate-resilient communities in Ontario will require strategic investments in wetland restoration, says Gloutney. DUC, he adds, “is prepared to come to the table.”

Coast to coast: more shades of green

Janine Wiebe is looking forward to the final implementation of her village’s green vision. They plan to add educational signage and trails around the new tertiary wetland site. They also want to invite environmental science students to conduct research there.

As they wait, cities like Moncton, N.B. are reaping the rewards of investing in green infrastructure.

By working with NPS staff, Moncton has integrated wetland-like naturalised storm water retention ponds into urban developments. These urban wetlands are able to store and filter vast amounts of water, which improve water quality as a result.

Elaine Aucoin, Moncton’s director of environmental planning and management found that these systems are functional, and add to the quality of life for residents. “Wetlands look a lot nicer, and provide the community with a place to gather around, unlike dry ponds that are often fenced off, and a waste of space,” says Aucoin.

In March, DUC president Jim Couch recognised the City of Moncton with a special “Ducks Unlimited Canada Order of Conservation” for its wetland conservation leadership.

Leading the green infrastructure revolution on the opposite side of the country is Gibsons on B.C.’s sunshine coast. The town gained national recognition when the Globe and Mail profiled it for declaring Nature its “most valuable infrastructure asset”. Their 2015 financial statements read: The Town is fortunate to have many natural assets that reduce the need for man-made infrastructure that would otherwise be required. This and filtration), creeks, ditches and wetlands (rain water management) and the foreshore area (natural seawall).

What gets measured gets managed. So important are these green infrastructure assets, the town made a pioneering decision to include them under the same asset management system as engineered infrastructure.

Walking over a footbridge spanning the springswollen Rat River, Wiebe says she understands why Gibsons values the potential of green infrastructure solutions that exist around us.

“Instead of working against nature, we should be working with it.”

Leigh Patterson

Leigh Patterson is editor of Conservator