Super User

Tracker dog helps find and protect birds

Emma Williams and I are helping the South Wairarapa Schools - Martinborough, Pirinoa and Kahutara - to achieve some of their environmental studies assignments and general objectives.

Emma has visited Kahutara School once already and her talk was very successful, she had her dog Kimi with her and the children loved that.

Then Emma went up to Hawke’s Bay and further north where she worked with older young people. Emma has developed a package for schools on wetlands and wetland birds with bitterns in particular, and where they are in the habitat.

Emma’s lovely black labrador Kimi, helps with her work and accompanies her on visits to schools.

We will start another series of school visits in the South Wairarapa during August and plan to visit Wairio wetlands at some stage and track bitterns that have radio transmitters attached to them.

The overall plan is to introduce pupils to wetland conservation and so attract some new young members for Ducks Unlimited!

Gill Lundie

Wairio Wetland Planting Day – June 22, 2017

Another great day on the journey to restore the Wairio Wetland!

About 40 good folk, including a large and enthusiastic contingent from the local Kahutara Primary School, turned up on a nice fine Wairarapa day to add 300 odd trees to the thousands planted over the last 12 years at the Wetland.

Don Bell, a great supporter of the project, had all the plants on site and some good keen lads from Palliser Ridge Station and Trevor Thompson from DUNZ had holes dug before the planting contingent from the school and others arrived. Thus, the actual planting proceeded at pace and all adjourned for refreshments before mid-day. Apart from one attempt at synchronised swimming (it is a wetland after all) all went to plan! It is hard to beat a day out in the elements helping to make things better in this land of ours!

Ross Cottle

Transformation of Mangaiti Gully

Earlier this year Jim Law took Rex Bushell on a tour of Wairio Wetland. Rex was impressed. He is involved with the Mangaiti Gully Restoration Trust in Hamilton. Mr Bushell was very impressed with the Wairio project.

When he arrived home Mr Bushell took the time to look on Google-earth to help locate the wetland in what he described as a “rather extensive landscape”.

Mr Bushell had spent three weeks touring the country, including the South Island and visited many restoration projects being done by both government institutions (like councils and DOC) and community driven ones.

“The one thing that stood out was that there can be no template to lay over any restoration project. Each one is individual both in people available (and their abilities) to run them and the natural area being restored,” Mr Bushell said.

“I returned to our home project, Mangaiti Gully Restoration Trust, full of inspiration by what I have seen.”

Mr Bushell was so inspired by all he had seen on his travels, he went on to write up a management plan for the whole 30 hectares of Mangaiti Gully.

“Ducks Unlimited are doing such great job,” was his closing comment.

Rex Bushell, Co-ordinator

854-0973 or 021-237-3857

http://gullyrestoration.blogspot.co.nz

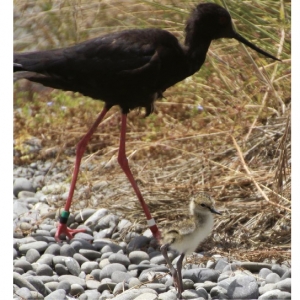

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki

The critically endangered black stilt/kaki (Himantopus novaezelandiae) is one of the most endangered birds globally and remains the rarest wading bird in the world, despite over 30 years of intensive management. The species is only found in New Zealand’s South Island and is considered a Canterbury icon.

The black stilt was formerly widespread throughout the New Zealand mainland, and was still breeding at North Island locations in the late 19th century. During the 20th century the range contracted from being South Island wide, to being confined to Canterbury and Otago in the 1950s, South Canterbury-North Otago by the 1970s, and the Mackenzie Basin by the 1980s.

Today the black stilt’s breeding distribution is limited to braided rivers and wetlands in the upper Waitaki River valley of the Mackenzie Basin. Breeding pairs are now confined to the area between the Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki basins in the north, and the Ahuriri River in the south.

The Department of Conservation (DOC) has managed the Kaki Recovery Programme since 1981, when the population declined to just 23 adult birds. The programme aims to increase the population by wild egg collection and captive rearing, captive breeding, predator control, and increasing public awareness. By 1991 the wild population still only consisted of 31 adult birds, while in 2010 the number had increased to 85 birds, and 130 birds in 2012. However, today there are still only 106 black stilts remaining in the wild and the species remains on the brink of extinction.

This is due to a number of challenges from a range of threats: introduced predators, habitat degradation, habitat loss, hybridisation with pied stilt, and human recreational disturbance. Intensive predator control is undertaken due to a whole suite of introduced mammalian predators, as well as native avian predators. These predators are prevalent across the area and are subject to major fluctuations. The development of irrigation has also seen major changes in land use in the Mackenzie Basin, particularly modification for conversion to dairy farming, resulting in extensive habitat loss.

DOC and The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT) are the only two organisations globally to captive breed this exceptionally rare species, in order to halt extinction. Annual releases into the wild of captive bred birds and predator control have undoubtedly prevented the black stilt from becoming extinct in the wild. Without this intensive conservation effort, the species would be extinct in less than 8 years.

ICWT therefore plays a pivotal role in black stilt conservation, with up to 61 birds per season housed in two custom-built aviary complexes. ICWT’s captive pairs produce three to four clutches each season, with all eggs generally transferred to Twizel for artificial incubation and hatching. More recently ICWT has also been hand-rearing chicks from Twizel, whilst a snow-damaged aviary there minimized capacity. Each season up to 50 juveniles are held at ICWT for pre-release conditioning until release in the Mackenzie Basin. At present there are 121 juveniles in captivity at DOC and ICWT, which will be released in August.

Releasing black stilts on the mainland remains difficult and continues to be a numbers game, even with intensive predator control and monitoring. Many of New Zealand’s threatened species benefit from translocations to predator-free offshore islands; however there are no islands with suitable braided river habitats for black stilt transfers, making releases confined to very limited sites. On average 120 chicks (from wild collected and captive bred eggs) are released annually, slowly increasing the fragile population. However the post-release survival rate is still only 33%, with even fewer birds becoming part of the breeding population. While the species may be rebounding from the brink of extinction (compared to the all-time low population in 1981), the black stilt still has a long way to go, with long-term survival remaining dependent on captive breeding efforts and rigorous predator control.

For these reasons ICWT intends to expand its black stilt capacity by 2025, by building a separate incubation and brooder room facility. This will broaden ICWT’s hand rearing capability and increase overall output for the Kaki Recovery Programme.

DOC has also just received $500,000 from Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), which will fund the replacement of the flight aviary which was destroyed in a 2015 snowstorm. This means the programme will again be able to rear and release an additional 60 black stilt juveniles annually

Sabina Lluecht - The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

President's Annual Report August 2017

It gives me great pleasure in presenting my annual report for 2016-17. While it may seem that we have had a quiet year DUNZ and its wetland conservation arm, Wetland Care NZ, has continued to support a number of very worthwhile projects.

Work at Wairio wetland on the edge of Wairarapa Moana continues with useful on-going research on a variety of wetland matters by Victoria University and their students. Further planting of wetland species has been completed and some additional work carried out on the bunds retaining the water within the wetland. The numbers and diversity of wetland bird species using the area is outstanding. Water levels go up and down over the year, depending on rainfall and inflow from the main lake, and this creates an excellent variety of habitat types. In mid-late summer when extensive shallow mud flats are exposed the wetland supports several hundred pied stilts, while in winter stilts are largely absent but replaced by several hundred waterfowl (black swan, shoveler duck, grey teal and mallard) along with numerous dabchick. During a recent visit by Ross Cottle, DU NZ Chairman and a sponsor they saw three bittern which is a real plus.

From the President

DUNZ has over the last 30 years supported, and often initiated, a number of threatened waterfowl recovery programmes (brown teal/pateke, blue duck/whio) which have been very successful and are now coordinated by other groups. DU’s role in lifting the profile of the endangered bittern (matuku) by supporting research by Dr Emma Williams has similarly been successful. Earlier this year an expert panel convened by the Department of Conservation reclassified the conservation status of bittern as “Nationally Critical” which places it in the same category as kakapo and takahe. This classification is the last step before “Extinction”.

Introduced Species

From around the mid-19th century, introduced species have often been considered an undesirable form of wildlife in many countries.

Introduced ‘invasive’ species have been routinely identified for removal in the belief that they damage or otherwise compromise the natural purity or integrity of ecosystems.However, diverse literature within both the natural and social sciences over the past few decades have questioned some of the assumptions underpinning these beliefs.

In contrast to the relatively static and human exclusive constructions of nature in the past, many authors now emphasize a nature characterised by indeterminacy, flux, interconnectedness, and hybridity. In consequence, discursive moves toward more reconciliatory approaches to the understanding of introduced species have become increasingly common.

Noting these developments, this thesis investigates whether changing discourses of nativism and authenticity are influencing the reconciliation of introduced species into socio-environmental systems in New Zealand. Recognising its efficacy for exploring discourses of ‘nature’ and ‘the environment,’ I employed biopolitical theory, along with concepts from the wider constructionist literature.

Biopolitics focuses attention on the expression of power over life itself and its attendant consequences. It highlights the discursive means through which ‘exceptions,’ such as introduced species, are delineated and removed. An analysis grounded in a biopolitical framework asks not only why death is considered necessary, but also why this death in particular is justifiable.

It thus offers a powerful means of exploring contestation over the supposed place or role of introduced species within constructions of an appropriate nature. I employed a critical discourse approach to interviewing, documentary research, and observations to investigate three case studies on introduced game species in New Zealand’s North Island.

Introduced game species were selected because they do not fit with common understandings of introduced wildlife in New Zealand, often being both demonstrably ‘damaging’ to native ecosystems and valued.

As such, they provided a vehicle for exploring both the types of discourse that may be necessary to reconcile introduced species more generally and how effects might be discursively rationalised. I found that species, whether native or introduced, were reconciled primarily as a factor of their perceived contribution to the national identity and economy. Species that were not considered useful were marginalised or ignored.

Despite the optimistic contributions of many authors arguing for the reconciliation of introduced species, I show that any broadscale reconciliation – at least in terms of a compassionate reconsideration – may be unlikely in New Zealand. As evidence, I show that notions of ecological balance and human-exclusivity remain popular in constructions of nature in New Zealand.

These beliefs necessarily exclude human introductions and, perhaps more notably, construct a belonging for humans in New Zealand as guardians or ‘archivists’ of native wildlife. Furthermore, a positioning of humans as ‘moral predators’ against a foreign invasion of introduced species reconciles peoples’ own place in nature.

Though often accepted as inaccurate, rhetorics of warfare work by suppressing nascent doubts about the need to kill introduced species. I show that human tensions with certain introduced species are only reinforced by the truth discourses of science, which further promote moral predation, and the economics of pest management, which have created an important industry out of introduced species’ removal. Together, these findings suggest that any reconciliation of introduced species, though intellectually compelling, is unlikely to be advanced on any broad-scale in New Zealand until alternative human roles within nature are identified and propagated.

Jamie Steer

What are Waterbirds?

Waterbirds have been defined as “species of bird that are ecologically dependent on wetlands”.

1.This is the definition used by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

2. Why count waterbirds?

has been adopted by the European Union to identify Special Protection Areas (SPAs) under the Birds Directive. It is also used by BirdLife International in the identification of Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in wetlands throughout the world.

3. What is the International Waterbird Census?

• Global coordination, and the counts in the Western Palearctic and southwest Asia are organised from Wetlands International

headquarters in Wageningen, The Netherlands.

• The African Waterbird Census is coordinated from a sub-regional office in Dakar, Senegal, which began operating in 1998.

• The Asian Waterbird Census, which includes Oceania, is coordinated from Wetlands International’s Asia Pacific office in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

• In the Americas, the Neotropical Waterbird Census is coordinated from the Americas office of Wetlands International in Buenos Aires.

• Establishment of IWC in North America began in 2003, from a new Wetlands International office in Washington DC. The census takes place every year in over 100 countries with the involvement of around 15,000 counters, most of whom are volunteers. More than half the effort is concentrated in Europe, but involvement in other parts of the world has increased markedly since 1990. Between 30 million and 40 million waterbirds are counted each year around the world, and details of the counts and the sites where they take place are held on the newly upgraded, state-of-the-art IWC database. The IWC is thus by far the longest running and most globally extensive biodiversity monitoring programme in the world.

4. How to count waterbirds.

- the size of the site; - the accessibility of the shoreline; - the availability of vantage points from which the site can be scanned; - the amount of time available to complete the count; - the number of people involved; - the available equipment. The most important element of waterbird monitoring methodology is standardisation.

Why Wetlands are Important

Wetlands and Nature.

Wetlands and People

Environmental benefits of water quality

Flood control

Wildlife habitat

Australian Duckshooting - here in NZ

exciting time of the year with hunters and their canine companions excitedly make

their plans for the annual ritual of spending time in the field hunting duck, quail & deer.

Chris Thomas, David Macnab,

Diane Pritt, Graeme Berry and

John Clayton.

(Yes, ducks were shot).

This unique private/public partnership created a game licensing system, and the funds from licences purchased by hunters delivered revenue that allowed government to acquire threatened wetlands. These wetlands provide critical breeding sanctuary for native waterbirds, offsetting habitat lost by drainage for agricultural and other purposes, and facilitate legal hunting during the prescribed season – a purpose that is often overlooked.

landscape.

volunteers.