Displaying items by tag: Wetland Restoration

Research scholarships aid restoration

Research scholarships aid restoration of native wetlands

Thanks to Wetland Care Research Scholarships funded by Ducks Unlimited, our student researchers are finding the best ways to recreate a haven for waterfowl.

Wetlands in Aotearoa New Zealand are precious natural resources viewed as taonga by Māori, which provide a habitat for fish and birds.

Even in purely financial terms, wetlands are valuable for their role in filtering nutrients from water, absorbing carbon, and controlling erosion and flooding.

Sadly, they are now in crisis. With over 90% of our wetlands lost over the past 100 years, many plants and animals are struggling for survival, including the elusive matuku (Australasian bittern) and pūweto (spotless crake).

Purple Loosestrife - pretty enemy

Help spot purple enemy at Lake Wairarapa

Wetland restoration under the microscope

Restored wetlands on private farms deliver ecosystem services and increase diversity, with varied results, a recent study has found. Shannon Bentley, a master’s student at Victoria University and the first recipient of a Wetland Care Scholarship funded by Ducks Unlimited NZ, is studying how wetland restoration on farms changes plant, soil, and microbial characteristics. In 2018-2019, as a part of the research group, Wetlands for People and Place, she sampled 18 privately restored wetlands and paired unrestored wetlands on farms in the Wairarapa.

For her master’s thesis, she analysed the wetland plant communities, soil physiochemical characteristics, and soil microbial communities to understand how they change with restoration. She found that wetland restoration on private property shifts plant, soil, and microbial characteristics towards desirable remnant wetland conditions. She also showed that the outcomes of wetland restoration varied within and between wetlands.

More than 40 per cent of New Zealand is held in private ownership, and private property holds huge potential for wetland restoration, containing 259,000km of stream length (Daigneault, Eppink, & Lee, 2017). Additionally, wetland degradation is extensive in lowland environments which are primarily in private ownership.

The outcomes of wetland restoration undertaken by landowners’ own prerogatives are poorly tracked. Private restoration is driven by personal preferences and finances, so the extent and form of restoration are varied. For example, the 18 wetlands sampled in Shannon’s study were restored in many different contexts and using many different techniques.

Wetlands differed in time since initial restoration (6 months to 42 years ago), size (0.4ha to 33.7ha), upstream watershed area (4ha to 2,263ha), dominant plant community (woody v herbaceous), and the number of restoration techniques used (2 to 8).Wetland restoration is beneficial for a number of reasons, but particularly for regaining wetland ecosystem services and increasing native biodiversity. Ecosystem services are ecological processes and functions that have beneficial outcomes for humans.

Compared with all other ecosystems, wetlands produce the highest levels of ecosystem services per unit area. This high production of ecosystem services is due to wetlands’ unique biology and geology resulting from their position at the interface of water and land. Wetlands are particularly effective at producing the ecosystem services of water purification, flood abatement and climate regulation through carbon sequestration.

Shannon found that with restoration, soils regained wetland traits, providing more ecosystem services. The restored soils had higher carbon content, lower bulk density, and lower plant-available phosphorous. Increased soil carbon content shows the carbon sequestration potential of soil expands with restoration.

Additionally, reduced plant-available phosphorous indicates restored wetlands can take up phosphorous and improve downstream water quality.

And finally, with increased carbon and reduced bulk density, water moves through the wetland soils slower to reduce peak flood heights.

Shannon found wetland soil microbes increased in biomass and fungal dominance after restoration. These changes, in part, explained the increase in capacity for wetlands to deliver ecosystem services.

Soil microbes are responsible for decomposition and nutrient cycling. A greater mass of microbes means restored wetlands have more capacity for biogeochemical cycling and decomposition, which can accelerate processes such as carbon burial, as

seen with the increased carbon in restored wetland soils compared with unrestored soils.

The presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) also increased after restoration. AMF help plants survive and reduce phosphorous in soils, thus contributing to cleaner waterways.

Each restored wetland showed a lot of variability of soil and microbial responses within and across wetlands. Because wetlands are found along a hydrological gradient between saturated soils and drier, upland soils, the microbial and soil properties differed according to the landscape position.

Soils close to the water’s edge, as a result of being saturated, had more carbon, microbial biomass, and more fungal biomass, and were less dense. By examining the plant communities, Shannon found that, after restoration, plant diversity increased within the plot and across the landscape. This means that with restoration, habitat heterogeneity increases, a beneficial outcome that increases ecosystem stability and the number of ecosystem services produced.

Additionally, she found that wetland soils and plant and microbial communities showed different levels of recovery that were not consistent with the length of time that they had been restored.

Some projects’ soil and microbial characteristics recovered faster than others. The main difference between fast and slower-recovery wetlands was the hydrological regime.

Restoration projects that occurred on isolated hydrological systems such as depressional, rainwater-fed wetlands took far longer to re-establish remnant wetland conditions. Projects undertaken on flowing hydrological systems such as springs and streams underwent successional processes faster to establish wetland conditions that have a higher production of ecosystem services.

The study has shown that restoring wetlands on private farms increases the ecosystem’s ability to simultaneously produce multiple different ecosystem services and support more biodiversity.

As food production demands continue to rise simultaneously as land becomes more scarce, agricultural systems are becoming more industrialised and intensive. This is placing pressure on natural ecosystems, as seen by reduced water quality, native habitat, and changing landscapes from carbon sinks to sources.

There is increasing recognition that we need mixed agroecosystems so food production does not compromise other ecosystem services.

Wetland restoration is gaining significant traction as a solution to issues surrounding water quality, climate regulation, flooding, and loss of native habitat, and this study has shown that private restoration is effective tool to do just this.

Shannon concludes her report by saying: “I would like to thank all the landowners that generously allowed us to sample their wetlands; each site we visited was so beautiful and unique.

“I thank Ducks Unlimited for the funding that allowed me to do this research. I also thank the Holdsworth Foundation, the Sir Hugh Kawharu Foundation, Wairarapa Moana Trust, and Victoria University for the financial support I have received.

“Finally, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr Julie Deslippe and Dr Stephanie Tomscha for their guidance and help in producing this research.”

Wairio on show

About 30 people braved squally rain on Sunday, May 9, for a guided tour of Wairio Wetland led by Ducks Unlimited NZ President Ross Cottle and Director Jim Law.

The event was a Rural Women New Zealand annual event to raise money for the Associated Country Women of the World to help fund community projects in developing countries.

Before setting out, Ross and Jim told the visitors about DU’s long involvement with the wetland – from Stage 1, its initial project about 17 years ago through to the latest development in Stage 4.

Ross said the wetland’s only water source in 2005 was courtesy of high wind dumping water into it from Lake Wairarapa to the west, but it didn’t retain it, and the water flowed straight back into the lake.

DU put in a bund wall, which was moderately successful, holding the water through the bird breeding season, but by December, it had dried out.

The next step was to dig down to a lower level to keep the water there longer, which was more successful, holding the water till the birds had bred and fledged. At the same time, DU planted out native species and these are now well established in Stage 1.

From there, it was on to Stage 2 and 3, and every low spot was fenced off with a bund wall.

Stage 3 was handed over to Victoria University because “we wanted some science behind it”, Ross said. It was envisaged that the project would provide a template for wetland restoration.

“Next thing, someone had a bright idea to put in a bund wall” between the three stages and the lake. About two weeks later, a mighty wind blew water in from the lake and “we had 100 acres of water”. After that success, DU extended the bund all the way back to Stage 1.

This was “amazingly successful” and has created a wetland of more than 250 acres of water.

“We were successful beyond our wildest dreams,” Ross said.

Jim said Wairio had been a ground- breaking project, with the Department of Conservation handing over the wetland’s management to DU – at the time it was unheard of for DOC to hand over restoration of its land to a local group.

“It only took us two years to convince DOC to let us spend our money on their land.”

DU has spent more than $200,000 in the past 17 years. About half of this has come from donations, which began rolling in once people saw how Wairio was being transformed and the return of wildlife.

On the 4.2km walk, Jim led the visitors along the bund wall track through Stage 4 of the wetland, where he described DU’s vision of the future – when stands of kahikatea would replace the current open areas of fescue.

With a rainbow in the background, and Ross bringing up the rear in his side-by-side to assist any stragglers, the tour covered Stages 3 and 2 before reaching its conclusion at Stage 1.

On a small detour from the main track to the water’s edge at Stage 4, the group had a preview of the proposed site for a viewing hide which DU has built. It is now waiting for a resource consent to place it on the site.

Birdlife has flourished at Wairio since DU took over, and the number of royal spoonbills, which previously had not been seen for 30 years, have surpassed 100, and they are breeding there.

Bittern numbers have remained stable in the past four or five years, despite a continuing decline throughout the rest of New Zealand.

Over a hot cuppa back at the cars, the visitors said the tour had been a revelation and they were highly impressed with their tour guides’ continuing passion and enthusiasm for the project.

Tracking wetland changes through eDNA

A study has shown that environmental DNA, known as eDNA, may be valuable in measuring biological changes in wetlands. The eDNA is extracted from soils, air, water, and other substrates.

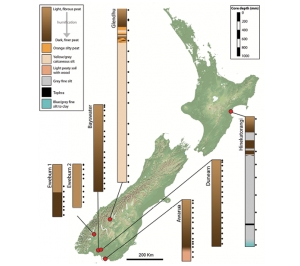

Researchers from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research sequenced microbial DNA from soil cores taken down to 4 metres below the surface in seven New Zealand wetlands in one of the few studies globally to have studied wetland microbes at such depths.

“The results showed distinct changes in microbial communities as we went deeper,” says study co-author Dr Olivia Burge.

Biodiversity monitoring in wetlands tends to focus on large organisms such as birds and plants, which can be relatively slow to respond to environmental change.

Lead author Jamie Wood says the strength of eDNA is that it allows researchers to study microbial groups (bacteria and archaea), which may respond faster to environmental change.

As a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission. This is

a process driven by microbes, and the researchers saw an increase in the types of microbes responsible in the upper

layers of the more modified wetlands.

“An unexpected finding was that the effects of drainage also appeared at greater depths, below the water table, where the relative proportion of microbes responsible for carbon fixation and methane generation decreased,” he says. As part of the study, the researchers compared three similar wetlands with different degrees of human modification. When a wetland is drained for agriculture, increased oxidation of the peat leads to more carbon dioxide emission.

“Ultimately eDNA may provide a useful tool for monitoring real-time wetland condition and identifying when critical thresholds are being approached,” says study co-author Beverley Clarkson.

Restored wetlands bring diversity

DU's inaugural scholarship recipient Shannon Bentley is in the final stages of analysing data for her thesis on wetland restoration.

She says she is exploring how restoring wetlands from pasture changes plants, microbes and soil.

"Restored wetlands are home to more diverse native plant communities and soil microbial communities than pastures, preliminary results show.

"This diversity produces a wide variety of benefits for people. For example, restored wetland soils have an increased capacity to store carbon, attenuate floods, and remove excess nutrients. "However, restoration creates a wide variety of responses, with every restored wetland being different."

More to come from this space, she says.

Wetland restoration methods studied

Victoria University student Shannon Bentley is the recipient of DU’s first Wetland Care scholarship.

Shannon, who is from Upper Hutt and Carterton, has a bachelor of science degree and is now studying for a master’s in ecology.

She is looking at facilitating effective wetland restoration in the Wetlands for People and Place research group.

“This project looks at wetland restoration in the Ruamahanga catchment, and my role in the project (in part) is to find the ecosystem services gained from wetland restoration,” she says.

“This project has been an amazing opportunity to contribute to the Wairarapa’s environment and clean up the Ruamahanga River.

“In the Wairarapa, farmers have been undergoing wetland restoration on private property. Farmers have used different restoration techniques to re-establish a wetland ecosystem,” she says.

“Wetlands produce services such as water purification, flood abatement, carbon storage, and species habitat.

“My master’s research asks how restoration, species diversity and ecosystem services interact.

“Specifically, I will ask how does restoration affect the biodiversity of plants and soil microbes? And how do biodiversity and restoration treatments affect the ecosystem services?

“With this information, I hope to be able to advise which wetland restoration techniques are effective at restoring ecosystem services.”

Her goal is to quantify the gain in nutrient retention, flood abatement, carbon storage, and plant and microbe diversity in 18 restored wetlands of differing ages in comparison to 18 unrestored wetlands.

“By measuring how wetlands are functioning (via ecosystem services) after they have been restored, and looking at what restoration treatments are effective, this project will be able to determine how effective our current restoration efforts are,

and which restoration techniques are working.”

DU Director Jim Law says, of Shannon: “She is exactly the kind of person that our scholarships are directed at. She is a bright, passionate young Kiwi.” Shannon’s supervisors are Dr Julie Deslippe, assistant director of the Centre of Biodiversity and Restoration Ecology at Victoria, Dr Stephanie Tomscha, head of the Wetlands

for People and Place project and a postdoctoral research fellow at Victoria, and Ra Smith.

Ra Smith is an environmental iwi liaison for Shannon’s iwi, Ngāti Kahungunu, and a whanaunga (relative). He is involved in the effort to clean up Lake Wairarapa.

DU's trip to a 'magic place'

The wetland at Nick's Head Station at Muriwai, south of Gisborne, is a world-leading example of positive human interactions with the land, and of what vision and money can achieve.

General manager Kim Dodgshun has worked at Nick's Head Station since 1994, eight years before the current owners bought the property. "They inherited me and we've worked well as a team ever since," Kim says.

When Kim arrived, the land that is now the main wetland was being grazed with livestock roaming all over, and with cows wandering along the beach. "It was nothing like it is today."

Early on, Kim had the idea of creating a bird reserve on the property and ran it past wildlife ecologist and former Wildlife Service ranger Sandy Bull.

The plan, however, hit a snag when the owners at the time said they did not wish to proceed with something that would not produce financial returns.

Undeterred, in 1995 Kim managed to obtain a $15,000 Natural Heritage Fund grant from the local district council and, with Sandy's help, starting trapping. "We caught a big polecat down on the beach," Kim says.

They also put up "No shooting" signs – it had been a popular duck shooting site, fenced off 15 hectares and planted flax around the outside. The birds flocked in, bringing seeds from other wetlands in the area and the plants began to grow.

The story of the wetland took another turn in 2003 when the farm changed hands after the Overseas Investment Commission approved an application from a US billionaire to buy the land, in what turned out to be a 12-month-long process.

He had first visited the farm in 2002 and embraced Kim's plans to create a wildlife reserve.

The final step for the sale was to gain iwi approval. Kim says communication was the key and once the iwi knew what the owner planned to do with the property, the deal was approved.

In response to Kim's plans, the owner said, "Let's make this bigger and better", and brought out renowned landscape architect Thomas Woltz from the US to design the wetland, with advice from Kim and Sandy.

A previous manager who had farmed there for 35 years had set in place the foundations to drain the saltwater from the low lying areas. He put up a netting fence on the beach which collected all the driftwood and storm debris, building a natural wall with sand.

Next, he added another fence on top of that and planted it out with marran grass and other plants.

Later, in the 1960s, a drain was put in to get rid of the remaining saltwater but a narrow, shallow channel remained, with 700 acres of catchment running into it. In summer it dried up. The surrounding paddocks were all very wet with no drainage.

Kim had already planted some native blocks but as Thomas Woltz learnt more about New Zealand and its trees, "the master plan was to revert the land back to how it was 700 or 800 years ago, with a profitable farming operation, back when there were no predators and the land was covered in native trees", Kim says.

Planting began in earnest in 2003 and now there's almost 700,000 natives on the property – coastal varieties with "the big fellas" – rimu, matai and totara – planted among them.

The wetland project began in 2005 – plans were drawn up, the land was surveyed and work began, initially with six diggers.

Kim had warned the contractors that trucks with wheels and 20-tonne diggers wouldn't work in the boggy terrain, but they brought them in anyway and all of them got stuck.

Which left the six smaller diggers. Firstly, a wall was put in to stop the saltwater coming in over the original wall at the beach. "We put in some more small ponds up the valley and worked our way west."

Deep channels – "about 2½-cars deep" – were dug out to ensure the wetland had water year-round.

The material excavated from the channels was made up of a layer of Plasticine-like blue tacky soil sandwiched between shells and "rubbishy" soil. The blue material was used to seal the walls or build the islands, while the "rubbishy" soil helped shape them.

Diggers scraped up the topsoil which was carted on to the shaped islands by trucks with tracks to prepare them for planting.

However, when they came to seal the western side of the wetland, they ran out of the blue soil so plastic liner had to be used in some sections.

"We pegged out all the walls and had three diggers in a row, one digging the holes, another with a big roll of the plastic, working at snail pace, unrolling it, with a third quickly filling it in before the walls collapsed," Kim says. Thankfully, it worked.

"Once it was all done, we had to pump all the water out. "We got council permission to pump it out into the sea over sheets of corrugated iron to protect the beach."

In the process, they found some old kahikatea, big, old stumps of trees, leading them to believe that, pre-settlement, it must have been an old kahikatea swamp.

"There are some stumps on the beach visible at low tide that have been dated at more than 8000 years old," Kim says.

As well as dealing with the challenges presented by the terrain, during planting, they encountered another problem.

Holes were dug with an augur, and some crystal rain put in with soil over the top before the tree was planted with a fertiliser capsule.

Later they went back to one of the islands to put in stakes to mark where the native plants were but found that most of them had been pulled out.

"All the rats were just pulling them out and eating the fertiliser caps. They were having a ball."

The answer was to use about 100 bait stations with Pestoff rat bait, from Farmlands, and "there were bucketloads of rats coming in," Kim says. It's slowed down now.

"That was just another little challenge. I can't believe how well the plants have grown."

Now the islands are all finished and planted with native trees – 10,000 trees to the hectare. On the hills, it's 2500 to the hectare.

The wetland has two 1ha islands and several smaller ones. All the islands are in place of valleys, which was Thomas Woltz's plan, imagining erosion coming down and islands forming.

At its peak, 25 people were working on the project. The labour was all local and all the trees were sourced from the Muriwai area. "Now the locals come to get our native trees," Kim says.

The farm is 3300 acres in total with nine kilometres of coastline. It runs Angus cattle, 285 breeding cows and 3300 sheep. This is likely to be reduced to 3200, with the aim of getting more out of fewer stock, by doing things better, "by selling them when they are ready to go and when the market is ready to take them".

"We are looking at the possibility of going down the regenerative farming path, though the steep contours of Nick's Head Station add to the challenge – more investigations in this area are required."

Facial eczema is a problem so the farm focuses on sourcing facial eczema-resistant stock. The farm uses dicalcic phosphate fertiliser, not straight superphosphate, and nitrogen, which was seldom used, has not been used for about eight years.

The station employs a staff of 16, who look after conservation, including a former DOC worker who does trapping and twice-weekly night shoots by bike, general hands, stockmen, groundsmen, a secretary, a citrus manager and assistant, who have 50 hectares of citrus to tend, plus contractors.

Kim pauses, distracted by something that needs fixing. "Everything we do on this place, we got to maintain it.

"We've got this magic place that we've all had something to do with and created what it is today. We can't let it go back. We can't let wild pine trees start growing.

"We've got convolvulus – we've got to keep taking it out – we've got kikuyu grass on the farm that we have been spraying, we have got to keep at it. "

"The old place never sleeps."

- The bus trip to Nick's Head Station was organised by Kees and Kay Weytmans, who provided delicious, nutritious packed lunches. Kees' efforts to make sure everyone was comfortable during the talks on the jetty by providing lucerne bales to sit on were also much appreciated.

- For more on Nick's Head Station, watch Thomas Woltz's Ted Talk at www.youtube.com/

watch?v=9VlY-3V63yI.

You win some, you lose some

In 2012 a wetland was created at DU Director Dan Steele’s property, Blue Duck Station in the Ruapehu district, but things haven’t gone exactly as planned. Water has tunnelled under the pumice layer – the hills are predominantly pumice – to the next hard layer, first creating an underground leak, which DU’s John and Gail Cheyne noticed during a visit.

Next came the washout: Dan says, “We first noticed pumice floating down the Retaruke River before we found the washout.”

As of publication date, the problem is still waiting for a solution.

Meantime Dan has not been idle but had to climb out of his gumboots for a day or two to head to the city, see The biggest conservation project on Earth.

The evolution of Courtney’s Close

On a parcel of land at Mangaone in Raetihi, in an area that was once an unproductive, narrow, boggy drain bound by strong ridges, co-owners Graeme Berry and Paddy Chambers saw a potential habitat for waterfowl.

DU Patron Di Pritt says, “Since Graeme and Paddy Chambers have been involved at Mangaone, from 2004, they have created six major wetland areas – ranging from an acre to 10 acres – which are all fenced and they have planted about 38 acres. Another four major ponds have also been created.

“It is an amazing achievement, and was fully supported by the previous owner, Jon Preston.”

Their latest project is Courtney’s Close, a wetland area they named after the Horizons employee who helped with the project.

They created it by splitting a 300-acre paddock in half and building a 650-metre deer fence. The wetland area now consists of four ponds outside the fence, and three, with room for two more, enclosed by the fence.

This means animals have access to water but are excluded from the lower wetlands and impurities are filtered out along the way.

Inside the fences Graeme and his partner, Bang, have planted natives, protected from the deer.