Super User

Wings over Wairio project

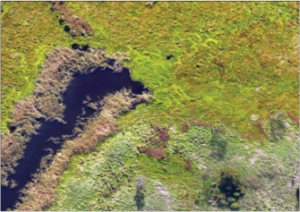

Victoria University master’s student Patrick Hipgrave is using drones to map wetland vegetation for his project on geographic information systems (GIS).

The project

What changes in vegetation cover over time are evident at Wairio?

To what extent is the accuracy of the image classification process improved with the addition of ancillary data?

This project investigates the use of image classification techniques to create detailed maps of wetland areas based on aerial photographs.

The project uses an emerging set of analysis methods called ‘object-based image analysis’ to investigate the applications of remote identification techniques calibrated to detect selected native and invasive species.

An additional objective is to compare and contrast the improvements that including ancillary data into the classification process, such as 3D digital surface models (DSMs) or near infrared imagery, may have over classifications based solely on true-colour images.

The processes being evaluated by this project may allow teams with limited budgets or time to quickly and accurately convert imagery into maps with much greater levels of details, which will improve their ability to detect and track specific plant species.

This is especially useful in the case of wetlands undergoing restoration as they often exhibit significant changes over time, and the target species would normally be challenging to differentiate from one another in an aerial photograph.

Results to date

Though the study is ongoing, with flights every three months, the initial results would appear to confirm that a ‘true-colour only’ classification would perform poorly compared with ancillary data. The improving effects of including infrared imagery will be tested once that has been gathered.

The classified images contain between 18 and 20 distinct classes.

Study area

The Wairio wetland was drained and converted into farmland in the 1960s.

Since 2005, it has been undergoing a managed restoration programme to return it to something approaching its natural state.

Several plantations of native plants have been established, and a weed eradication programme to control invasive species such as Bidens frondosa is in progress. This project can assist this effort by tracking the distribution of natives and weeds.

Object-based image analysis

Object-based image analysis works on the principle that different types of surface cover have unique properties, such as colour, texture or shape.

For instance, weed species might be distinguished from grass as the weeds may be a different shade of green to the surrounding grass, or present a unique textural pattern owing to differently shaped leaves.

- Patrick Hipgrave’s supervisors are Dr Stephen Hartley (School of Biological Sciences) and Dr Mairead de Roiste (School of Geography, Environment, and Earth Sciences).

- Special thanks to Daniel Kawana (Department of Conservation) and the Wairio Wetland Restoration Trust.

- For more details, email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or tel 021 0228 9824.

The sensors being used in this project are the DJI Phantom 4 Pro Camera, to collect true colour imagery, and a Micasense RedEdge-M, a multispectral sensor for collecting near infrared imagery. The software is ArcGIS Pro 21, ENVI 5.4 and PrecisionMapper 3.32

There’s a road through these wetlands

Gordon Pilone tells the story of how Pohangina Wetlands, now protected by a QEII National Trust covenant, were created

In 1995 Gordon and Anne Pilone bought a lifestyle block in Pohangina Valley, retiring there from Palmerston North where Gordon, originally from California, had lectured on and researched microbiology at Massey University and Taranaki-born Anne had established the best veggie and landscape gardens in town, which would prove valuable experience later.

Beside the Pilone property, sheep and bulls were grazing on a very wet paddock with some remnant kahikatea (New Zealand white pine) and other wetland flora struggling to survive. This farmland, owned by Finnis Farming Company (John and Mary Culling), had historically challenged owners’ efforts to drain it.

Across the road was the well-established Luttrells White Pine Gardens and Museum. The

gardens had walking tracks but only one small pond to attract wetland wildlife. And so began Gordon and Anne’s long-term retirement project to create a large, mature wetland. They set up the Gordon and Anne Pilone Charitable Trust in August 2000, and were joined by farmer and orthotist Chris Pullar and accountant Ian Mackrell as trustees. A fifth trustee, naturalist Dr Liz Grant, joined later, contributing her expertise in visual design and entomology science. All are Ducks Unlimited members.

Shaping the wetlandsThe development took off in 2001 when the trust employed contractor Kevin Large with his digger and bully to create the first pond near the main entry gate along Pohangina Rd. This is now known as the kahikatea block. Progress was slow as the wet dirt, being moved to create a pond, was used to develop the head and track along the bund, but it needed time to dry to get access.

Then in 2004 floods struck Pohangina Valley. Roads and bridges were washed away and Pohangina Rd was cut off when the culvert bridge at Sandy Creek was washed out. Pohangina Wetlands became even more soggy, but no damage occurred because the “wet” of the wetlands comes from aquifers and not directly from water flowing on the surface from creeks, streams or rivers.

Development slowed down after the flood because Kevin was involved with clean-up work in the valley but activity continued with the planting of native grasses, bushes and trees, mostly by Anne.

Because of the slope, all the surface water that overflows in the wet months flows to the southernmost part, the base of the damsite block. Until 2012, this water drained directly to the Weka St drain and the river. But Gordon found a way that this flow could be reused to establish a different habitat within the wetlands.

In 2006, work began on the second block (damsite block) and the biggest pond (0.54ha), which includes a sizeable island and a subterranean island – sometimes visible in the drier seasons.

Work on the “big pond” was challenging and a large track-dump truck and extra help

were required to take away the soil. It was also a large block (2.3ha) to plant out so Anne was flat out growing and planting and weeding. It is now maturing nicely and has a

“lookout”.

Once the damsite block was completed, Gordon convinced the other trustees that additional property would be fruitful for the future protection of the two main blocks.

The kahikatea block formed an L-shaped property with the newly developed damsite block, and the triangular block nestled in the “L” was being used for grazing. In 2010 this land was bought and designated the Culling block.

Instead of extensive pond development and native plantings, the block, essentially, is being allowed to “develop on its own”. Some earth was moved by Tim Luttrell with his small digger to provide a flow of surface water and a few flax, cabbage trees and Carex

geminata (cutty grass, rautahi) have been planted among the rushes.

The wetlands slope dramatically towards the Pohangina River, and the aquifer and surface water flows from north to south. This enabled the creation of ponds of varying depths and in the drier months, muddy areas form at the upside of the ponds. This habitat is invaluable because it attracts wading birds that feed in the “mudflats”. So watch out for pied stilts, heron, royal spoonbill, spur-winged plover, and dotterel.

Finnis Farming Co allowed the trust to acquire a small (0.2ha) parcel at the back of the damsite block from which Tim created a series of shallow ponds, with final exit of water overflowing to the Weka St drain.

Retention of water in this block is being aided by the planting of raupo (bulrush, cat-tail). This will create a new habitat and will allow shy and uncommon wetland birds to be seen such as fernbird, crakes and bittern. Even if this is wishful thinking – because the area is small – raupo swamps are ideal as filters for water purification.

Challenges along the way

Even with the best planning, things can go wrong and sometimes reworking is necessary, and costly. In 2006 it became noticeable that the big pond in the damsite block would not maintain its full overflow level for long after a wet period, but dropped quickly, exposing the subterranean island and pond bottom.

When walking along the track behind the head next to the drain, a wet patch was apparent so an exploratory ditch was dug along the pond below the base of the head. It exposed a cluster of rocks which seemed to form a drain into the head since water was trickling from them. It is likely this had been a very wet paddock, with drainage created from a ditch filled with rocks, and these were not noticed when the head of the big pond was developed. All agreed the remedy was to cut through the head and remove the rocks and rebuild it.

During a trustee tour after the Eketahuna earthquake in January 2014, it was obvious the poplar pond in the kahikatea block was extremely low. This pond is where the “waterworks” pipe crossing the pond head with an upright was built to allow discharge of the pond water to different levels. We thought it would be clever to be able to control the water level and form new habitats (for example, exposed muddy areas) at will. Well, Mother Nature thought differently.

The reason for the low water level became apparent when Anne found water leaking from the outlet side of the pond hidden in tall grass near the end of the pipe running through the head of the pond. On further inspection, there was a large crack in the plastic T-fitting at the base, which must have happened in the earthquake.

The T-fitting was held snugly by two posts and apparently there was not enough “give” when the earthquake hit. The assembly was removed and the pipe carrying water through the head was capped off on the inlet side of the pond. We learnt that careful thought needs to be given to the design of piping in a wetlands system.

Another example was during the development of the ponds in the kahikatea block. The main ponds there are connected by 110mm pipes allowing water to flow from one pond to the next underground rather than over the tracks, ensuring easier and drier access

for visitors.

Gordon had a bright idea to prevent clogging of the inlet of the pipes with surface debris: the inlets could be fitted with a short pipe at a 45-degree angle to submerge the inflow beneath the surface of the pond. Soon after this modification, he was surprised to find all the ponds had lower water levels than the expected overflow levels when the ponds were full.

The penny dropped and it became obvious that the inlet-angled pipe also allowed for siphoning to occur when the flow was great enough to fill the pipe and continue to flow to the level of the submerged inlet. A lesson learnt. And the solution was obvious, too – drill a hole at the attachment point of the angled pipe to allow the inflow of air, thus preventing siphoning.

Some other “oops” happen unexpectedly and require major adjustments. In 2011 Gordon began to have cramps in the calves of both legs. Peripheral arterial clogging was advanced and in 2015 he had to have both legs amputated above the knees. Now wheelchair-bound, Gordon is no longer physically active in the wetlands development, but fortunately the main work is complete.

Anne continues maintenance plantings

Tim Luttrell.

The Pilone home could not be readily renovated for wheelchair living but, fortuitously, a cottage being built across the road by Tim and Carol Luttrell became available and was purposefully built for wheelchair use. You will still see Gordon in the wetlands, but not on his tractor mowing or on his bright orange Kubota RTV.

Instead, he will be observing and taking pictures from a Timmobile, a mobility scooter renovated by Tim. So look out for Gordon on the tracks and have a chat, or come to the cottage across the road and say hi.

Visitors always welcome

The wetlands were opened to visitors on the longest day in December 2005 and are always open to visitors at no charge. A brochure is available at the entry gate on Pohangina Rd.

Probably one of the greatest joys in establishing a wetlands was seeing a kōtuku (white heron) visiting for a few hours in 2008. This has been a one-time event, though it may be that they visit when we are not in the wetlands.

Another uncommon visitor is the New Zealand royal spoonbill (kōtuku ngutupapa). A young individual was seen for several days feeding in the shallow ponds. Some flock yearly at the Foxton beach estuary nearby. Since the first bird seen in March 2007, we have had increasing numbers visit and stay for several days, sometimes in flocks as big as 13.

Another resident wetland bird that delights visitors is the dabchick (wewei). During breeding season, you can find one or two white striped headed chicks on the back of an adult with the mate diving and bringing food to the chicks.

Luttrells wetlands and kahikatea bush

Next door to Pohangina Wetlands and hidden by the magnificent tall stand of kahikatea is another developing wetlands area on the property of Tim and Carol Luttrell.

Luttrells White Pine Gardens and Museum is open any time by arrangement for a small fee. The complex is well-worth seeing and includes a walkway through kahikatea bush; tracks meandering around wetlands; and plenty of opportunity to view wetland wildlife and a comprehensive museum based on settlers in the valley.

Pohangina Village residents are fortunate to have such an extensive wildlife habitat of 10ha (25 acres), combined, within walking distance of their homes. To assure it is kept in perpetuity for future residents, the Pilones and Luttrells have been granted Queen Elizabeth II National Trust covenants on the portion of their properties that constitute wetlands and bush. We are grateful and honoured that the QEII National Trust has regarded the properties as worthy of protection.

Now that the future of the two wetlands are secure, it is interesting to speculate what form of management might develop for their continued maintenance. Pohangina Wetlands, now under the auspices of the Gordon and Anne Pilone Charitable Trust, already has some long-term management permanency in the “turnover” of trustees, as well as financial assurance as the beneficiary of the Pilone estate. The Luttrell wetlands and kahikatea bush belong to the family, but the long-term future is unclear.

As the two properties are beside each other, separated only by a road, and wildlife interaction is seamless, it seems logical that the two properties be managed as one. In Manawatu, there already are open space properties being managed by some level of government using subcontracted maintenance. This might be considered for the future management of the “Pohangina Village Wetlands”.

We look forward to seeing you in the “wetlands a road runs through”.

Visit www.pohangina.org for more information.

White-eyed wanderer

The white-eye, hardhead, brownhead, aythya australis australis, or karakahia is a pochard – a diving duck closely related to the scaup. Strangely, its Maori name is also used, as an alternative name for native grey duck or pārera.

It is present in considerable numbers in eastern and south-western Australia.

When it first appeared in New Zealand, is not known for certain, but it was first recorded by Professor FW Hutton on Lake Whangape in the lower Waikato in 1867 and a year later recorded in abundance on lakes Waikare and Rotomahana.

So abundant was it that local gentlemen, after worshipping God and praising His creations, regularly took a leisurely punt and shot them in their hundreds, if not thousands.

Needless to say, game management procedures were not functioning at that time and apparently foresight was not generally prevalent. It was yet again a fine example of European greed and stupidity in the colonies, rather akin to hunting to extinction in Tasmania, both the Tasmanian tiger and the Tasmanian Aborigines.

Unsurprisingly, this duck appears to have moved on and perhaps all but died out, for there are no records of it having bred successfully.

But reliable sightings continued from time to time. Were these the ‘vagrants’ they were passed off as? Or were there small residual populations maintained in out-of-the-way, somewhat safer localities?

Sightings appeared from Lake Tutira, Lake Tarawera (in large numbers) Te Aute, Hamurana Springs, Wairarapa, Manawatu, Lake Ellesmere, Otago, and much more recently, near Napier (several times).

It would be interesting to know what the factors were that moved so many white-eyes into New Zealand in the 19th century – or indeed did they? Perhaps they came across in substantial numbers a lot earlier?

Since their breeding is influenced considerably by climatic conditions and they must nest very close to water, perhaps a particularly vicious drought sent them eastwards seeking water, aquatic food and a cooler climate?

Interesting too, to consider their disappearance from New Zealand. Was it entirely due to human intervention?

Shooting on that scale had to have had an impact but it is unlikely to be the only factor. At that stage of our colonial history, introduced predators are not likely to have been well enough established in sufficient numbers – except for rats. In those years there were serious rat plagues that may have contributed to the ducks’ demise. Were we in the grip of a drought? Apparently not.

But in 1886 Mt Tarawera erupted, and it erupted with an uncommon vengeance.

The lakes of the Tarawera region had at various stages contained white-eye populations. And not so very far away were populations on the Waikato lakes.

Naturally when Mt Tarawera spoke, everyone wished to leave town – ducks included. The eruption quite possibly dispersed the duck population far and wide.

Perhaps too, the ash showers may have significantly affected food supply – both terrestrial and aquatic. Continuing earth tremors and general rumbles would certainly have given incentive to move and keep moving. The species are very gregarious, so presumably they might stay together to some degree. But where?

Could they have returned to Australia – against often strong prevailing westerlies? Rather unlikely. Perhaps they went south, but it is unlikely in a

species adapted to at least a temperate climate. Maybe they went eastwards into the vast Pacific. Again there is no substantial evidence to suggest this.

There remains the possibility that they went north and north-east to the Pacific Islands. Interestingly, they have been frequently reported from various island groups.

Or did they simply disperse throughout New Zealand, and never bred much, if at all, for they are known to be reluctant breeders and also wary of human company.

Even in Australia, they are thought to be in some decline in recent years, presumably due to habitat degeneration such as the usual: drainage.However populations are still pretty impressive: during the 1957-58 severe drought in southern NSW about 80,000 white-eyes dropped into Lake Brewster, 50,000 at Barrenbox Swamp and a mere

15,000 at Lake Learmouth (Victoria).

Perhaps now is the time, before numbers do lessen, to reintroduce this species into New Zealand. Whatever the populations, putting your eggs in various, good quality, safe baskets is still a very sound strategy.

Considering the self-introduction and therefore indigenous status of this bird, like the other white-eye or waxeye (tahou) and a handful of other Australian species, perhaps it deserves a little help.

A little help like the grey teal – a non-endemic species – received so successfully. Surely white-eyed ducks have a far greater eligibility for residential assistance than say Carolina

wood ducks, mandarins, whistling tree ducks, mallards, Canada geese!! and mute swan.

▪ Alan Fielding lives in Masterton and is a Life Member of Ducks Unlimited. He previously taught environmental technology and education at tertiary level and had a wetland, which he developed, at Tokomaru, northern Horowhenua.

A long way from home

DU member Diana Chetwin was surprised to spot a rare visitor from the south and now her sighting has been officially confirmed.

On December 2017 I was helping to launch a boat at Sandy Bay, Te Awaiti, South Wairarapa, when I heard the sound of pied stilts; looking down the beach, I saw two birds take flight. One appeared to be darker than the other.

After launching the boat, I walked along to the next bay to see if the birds had landed there. Sure enough, they were fossicking in the rock pools as it was low tide. One was a black and white stilt and the other was clearly a black stilt (kakī).

I had my little camera and was able to get close enough to get a few pictures, but not so close as to disturb them again. The black stilt was banded, but unfortunately it was standing behind a low rock ledge so the feet and coloured leg bands could not be seen properly.

The sighting was reported to the Department of Conservation and the breeding programme at Twizel in Canterbury. Conversations with people there revealed that the black and white stilt was a hybrid from breeding with a black stilt and the other was clearly a black stilt in the North Island.

My photos only showed the bands on one leg, so they were unable to provide any more information on its breeding, but it was definitely from the South Island.

Climate conditions before the sighting were exceptionally dry for the month but there had been rain the week before. No storms though.

The sighting was reported to the Ornithological Society of New Zealand as an unusual bird recording and officially recorded

Record results for black stilt

A record number of endangered black stilts (kakī) were released in the Mackenzie Basin in spring after the most productive captive breeding season on record.

Overall 184 kakī were hatched and reared for release by the Department of Conservation, including 49 by the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust (ICWT).

In 1981, when the population plummeted to only 23 known birds in the wild, measures were taken to manage this tiny population.

Kakī, once widespread throughout wetlands and braided rivers throughout the South Island and lower North Island, remain categorised as critically endangered and are the rarest wading birds in the world. Their range is limited to the harsh environment of the Mackenzie and Waitaki basins, often snowbound through the winter months and drought affected during summer.

Controlling stoats, ferrets and feral cats across the Tasman Valley is critical for kakī to survive in their natural habitat.

Without predator control, fewer than 30 per cent of young birds survive. In areas with trapping, the survival rate is 50 per cent.

Captive breeding facilities operated by ICWT and DOC are an essential conservation tool to bring the species back from the brink of extinction, with genetic management one of the multiple tools used to optimise captive breeding outcomes.

The Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust continues the conservation work of Sir Neil and Lady Diana Isaac who bequeathed all their assets into the self-funding charitable trust, to continue their legacy and commitment to conservation.

▪ Catherine Ott is the administration manager for the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust

Pukaha releases shore plovers

River wins national award

Most improved river

Ōtukaikino River in Canterbury took out the supreme award for most improved river at the New Zealand River Awards 2018 late last year.

The river originates as a spring-fed stream on the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust property, west of Christchurch. The stream supplies commercial salmon farming water races, flows through the Isaac Quarry and the trust’s captive bird breeding aviaries, and across the Isaac sheep farm before continuing downstream into neighbouring properties.

The river is part of a greater restoration programme being undertaken by Christchurch City Council which involves the staged removal of willows and scrubby weeds, followed by more than 195,000 eco-sourced native plantings.

The Isaac section of the Ōtukaikino is fenced off from prohibited stock, with a generous corridor of land provided to maximise the riparian planting zone along the waterways edge. Walkways have been formed along a significant stretch of river, extending between the

Isaac Loop Track, Lake Roto Kohatu, Clearwater Golf Resort and the Waimakariri Recreational Reserve via the Isaac Farm Track.

The riparian plantings are all endemic to Canterbury. The land has been cleared manually, using brush cutters, machetes and axes with the slash left in piles as shelter from the Canterbury winds. This also provides a habitat for wildlife including invertebrates, increasing the biodiversity of the site.

Combi guards are used to mitigate against hares. Mulch is used when available, with some irrigation during summer. Initially maintenance spraying continues until a native canopy is formed. Ground preparation is minimal, with no fertiliser applied, so the natives must sustain themselves in the toughest environment from the outset.

The Ōtukaikino waterway demonstrates that a collaborative effort (from multiple landowners and organisations) can achieve significant ecosystem restoration, for the benefit of all.

Plan your visit

- Park in the Clearwater Golf Resort main car park.

- Follow the Ōtukaikino River pathway (beside the car park) upstream.

- Cross the river on the pedestrian bridge to continue on the Isaac Loop Track.

- Allow one hour return.

DU director takes up DOC role

DU director and bittern expert Emma Williams’ workload has become a whole lot busier after she was appointed science advisor (wetland birds) for the Department of Conservation in October.

A fulltime job for four years, her main task is to deliver the national bittern research plan. The role also involves work with other wetland birds such as spotless crakes and marsh crakes with the aim of setting up new collaborations with organisations to try to fill some of the knowledge gaps about cryptic and native wetland birds.

Projects include working with Stephen Hartley and students at Victoria University in Wairarapa Moana. One of the current projects involves putting out artificial bittern nests in several study sites, including Wairio, to determine what predators are targeting bitterns.

Emma says new bittern monitoring projects in South Kaipara, Auckland region, Tauranga and Turangi are expanding DOC’s national monitoring reach. The goal is to identify where bittern strongholds and hot spots are and inform where new projects are needed to try to reverse bittern declines.

Conference 2019 – save the date

Planning under way

Planning for this year’s conference and AGM, which will be held in Wanganui/Whanganui from 2-4 August, is well under way.

The conference venue and accommodation will be the Quality Inn Collegiate, a five-minute walk from the city centre.

The programme will include a field trip to Bushy Park Homestead and Wildlife Sanctuary, with lunch at the category-1 heritage-listed Bushy Park homestead, built in 1906.

The trip will include a stopover at Virginia Lake, pictured, where DU released a number of mute swans several years ago.

Bushy Park is considered by Forest & Bird to be among the 25 best restoration ecology projects in Australasia.

The sanctuary is home to hihi (stitchbird), tīeke (saddleback), toutouwai (North Island black robin), kereru and many other species.

A revegetation project in the wetland area of the park includes plantings of rimu, pukatea, mahoe, karamu, hangehange, pigeonwood, kawakawa, NZ flax and toetoe.

Time to clear out the cupboards

For this year’s conference, DU directors are asking members for donations of suitable auction and raffle items, particularly DU Canada merchandise that you have bought at previous auctions and are in good condition.

Canada DU items have become too expensive to import because of the shipping costs.

Email Will Abel (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) to let him know what you can contribute to make this year’s auction the best yet.

You can either bring the item/s to conference or drop them off with someone who is going, but please let Will know in advance.

Gift from a ‘Man of Trees’

Ducks Unlimited NZ received an unexpected windfall in October – in the form of a $2000 bequest.

Lifetime conservationist, author and former farm forester John Bracken Mortimer QSM, died at Waikato Hospital in May, aged 94. He was a former president of the New Zealand Farm Forestry Association.

Many environmental groups and other organisations have benefited from Mr Mortimer and his wife Bunny’s generosity but their greatest legacy is Taitua Arboretum, which they gifted to the City of Hamilton in 1997.

Hamilton Deputy Mayor Martin Gallagher says the Mortimers’ gift will be enjoyed for generations to come.

“John and Bunny’s legacy is immense,” Mr Gallagher said. “They have given the city one of its premier natural locations with an act of incredible foresight and generosity.

“The city owes John and Bunny a huge debt of gratitude.”

The couple began developing Taitua Arboretum in 1972 on their property west of Hamilton. They planted hundreds of trees on the 20-hectare block, before gifting it to the city. It formally opened to the public for visits in 2004 and has more than 1500 species of trees.

Mr Mortimer and Mrs Mortimer co-wrote several books, including Trees for the New Zealand Countryside: A Planter’s Guide and Trees and Their Bark: A Selection with Stories and Pictures.

DU is grateful for the kind gift from Mr Mortimer, fittingly described in the tributes paid to him as a ‘Man of Trees’.